Brenda Flyswithhawks, Santa Rosa Junior College professor of psychology, is pleased with the recent NAGPRA updates, even if her first thought was, “Well, here we go again.”

But she has caveats. “There’s one thing to get a regulation — you can write a policy, you can revise a regulation. But implementing that policy, or new regulation, holding these institutions accountable — that’s the challenge,” she said.

Museum directors and faculty members at community colleges taking care of Native American collections must comply with updated Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act 1990 (NAGPRA) regulations. However, they will need to do so with little to no support from their individual colleges or the California Community College system.

Across the nation, museums and institutions have closed Native American exhibits in response to recent updates to NAGPRA. The updates, made effective on January 12, 2024, refine how museums and institutions should repatriate or dispose of Native American human remains and cultural items which include funerary and sacred objects and items of cultural patrimony.

Since 1993, several updates have refined the 1990 Act. The most recent updates include two significant changes. The first is that Native American items can’t be displayed or used for research if the museum or institution has not consulted directly and received explicit permission from the tribe. The second important change makes it the museum’s responsibility to contact the tribe. This is important because previously, institutions such as the Interior Department have not repatriated objects because they were not legally required to begin the process unless a tribe or Native Hawaiian organization made a formal request, as ProPublica reported in January 2023.

In California colleges, the reparations process moves slowly, if at all.

Flyswithhawks, who is from the Qualla Boundary territory, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, has taught at SRJC since the college recruited her in 1989. She has been involved with the SRJC Multicultural Museum since that time, when it was called the Jesse Peter Native American Museum under the direction of Benjamin Benson, SRJC professor of anthropology.

The following year, NAGPRA became law. Museums and institutions have had over thirty years to repatriate cultural items and human remains. But, as of today, nearly 100,000 Native American human remains have not been returned, according to a ProPublica investigation.

Grant Parks, California State Auditor, found that in the California State University (CSU) system, only 6% of the Native remains and artifacts have been returned, and more than half of the campuses with NAGPRA collections have not returned anything to tribes. In his state audit submitted to the governor and state legislature in June 2023, he stated that more than half of the CSU campuses “do not yet know the extent of their collections and cultural items, despite federal law requiring them to do so by late 1995.”

The challenge for institutions and museums, then, is compliance. “Because they’ve not been held accountable for the old regulations,” Flyswithhawks said.

According to the state audit, CSU campus officials responsible for NAGPRA compliance blame a lack of prioritization and inadequate staff and funding.

The updates will impact many artifacts held by Santa Rosa Junior College Multicultural Museum. But the museum’s star exhibit — the Elsie Allen Pomo Basket Collection — is solid. The museum proudly displays the handcrafted baskets of the large collection that was entirely created and curated by Native American weavers.

Elsie Allen made it clear that she wanted the baskets to be grouped in a collection for display and negotiated or collaborated in person with curators to develop the exhibit. Genevieve Allen Aguilar, daughter of Elsie Allen, donated the basket collection to the museum in 2003.

Other exhibits, however, will pose greater challenges for compliance with the recent NAGPRA updates.

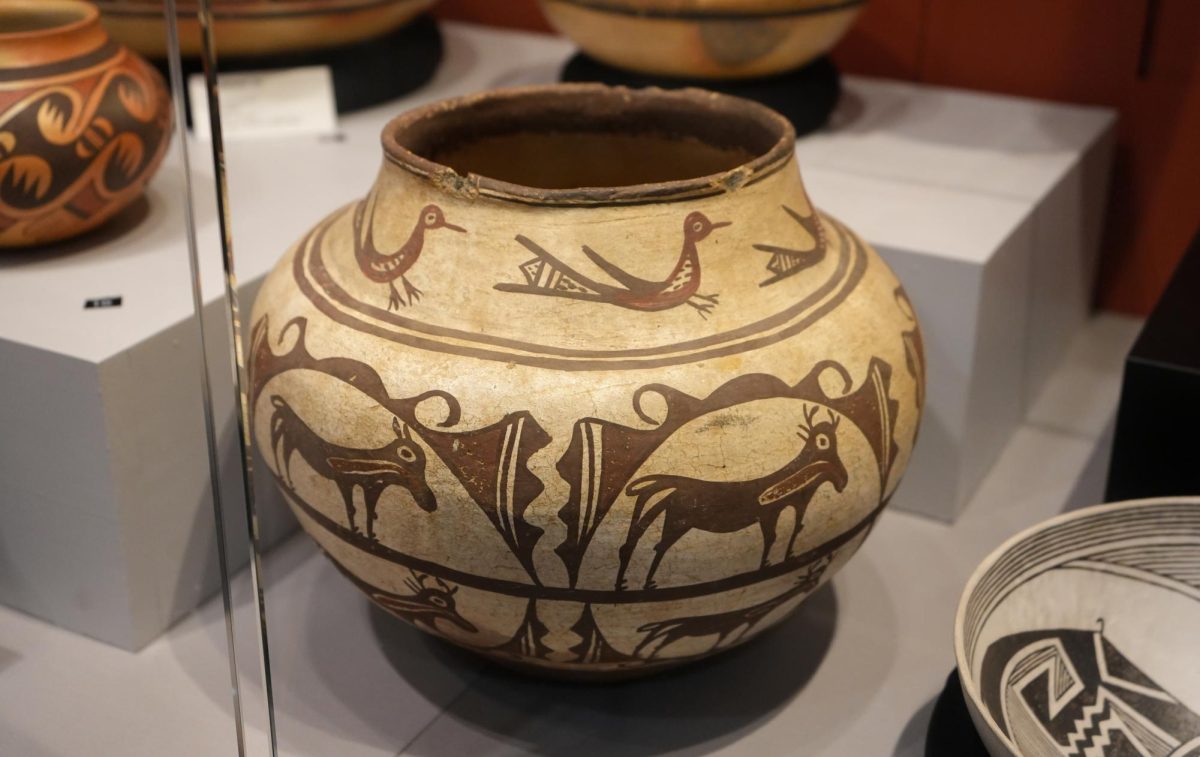

Some of the SRJC Multicultural Museum collections date back to an earlier era when archeological digs resembled opportunistic looting. Such materials formed the basis of the museum’s original collections. According to “The History of the SRJC Multicultural Museum 1938-2018,” (updated in 2021) one prolific collector, Jesse Peter, “well known for his exciting expeditions, which he called ‘hunts,’” contributed rocks, minerals, and “specimens of anthropological interest” that he’d gathered on his family’s property and in Sonoma County.

In the 1930s, Peter participated in group expeditions to Rainbow Bridge and Monument Valley located in Southern Utah. The explorers excavated ancient dwellings and claimed artifacts from them, which they gave to the National Parks and universities, including SRJC.

Rachel Minor, curator and supervisor of SRJC Multicultural Museum, acknowledges the challenge to establish tribal lineage for objects from the Peter’s collections. Most lack specific details for tribal affiliation or geographic location. Some only have the number “35,” which Minor interprets as the expedition collection year (1935). For items such as these, which tracing lineage yields no concrete results, Minor hopes for a collective repatriation among multiple tribes. “I’d like to see a few tribes decide to collectively bury mortars and pestles in an undisclosed location,” she said.

Yana Ross, SRJC Multicultural Museum volunteer, leads tours for elementary students. Ross grew up on the historic Graton Rancheria and is an enrolled citizen of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, a tribe composed of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo. She’s also Mishewal Wappo and Dry Creek Pomo on her mother’s side. She has followed the slow progress of reparations at other institutions, like UC Berkeley, and chairs her tribe’s Sacred Sites Protection Committee. “When there’s injustice in the world, for so long, you get used to surviving with cognitive dissonance,” she said.

But with updates strengthening NAGPRA, she takes hope. “It feels good that this is happening, that these ancestral remains are returned,” she said, her voice breaking. “It feels really gratifying and it’s kind of, it’s amazing,” she said about the repatriation process at SRJC Multicultural Museum.

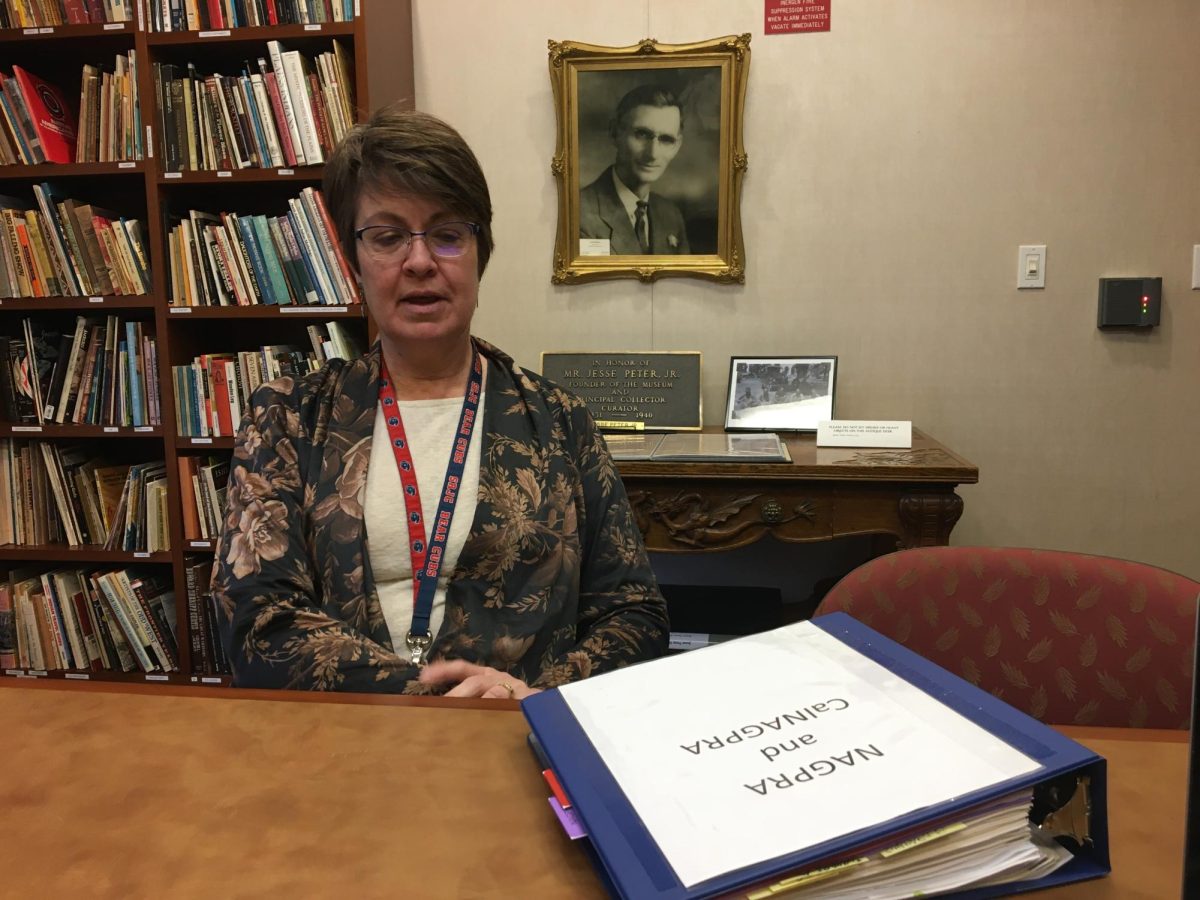

The SRJC Multicultural Museum spent several weeks following the December 2023 updates to figure out how the updates will impact their exhibits. “We are dedicated to the repatriation process and have built many strong and positive relationships with tribes through consultations, both in regard to our exhibits and the collections,” Minor said.

Unlike CSU and UC campuses, the SRJC museum does not have any human remains. Additionally, the museum does not have sacred or funerary objects, said Minor.

Minor, who has been at the museum since 2018, got more actively involved in NAGPRA regulations during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic when she had the uninterrupted time to take a deep dive into NAGPRA regulations. She took webinars, honed her skills reading legalese, and started taking stock of the collection.

While the museum has made no reparations to date, 32 objects are in the process of being repatriated, Minor said. Since 2020, she has sent 136 letters to tribes but only heard back from about two dozen so far. Sometimes letters are returned for the incorrect address. In these situations, Minor turns to a national NAGPRA expert who has access to a much larger database of contact information.

Once a tribe responds to Minor’s letter, the next step is to consult with tribal representatives. After the tribe makes a formal request for repatriation of a cultural item, there is a mandatory 30-day waiting period to give other tribes the chance to assess and make any claims if the lineage is disputed.

Some obstacles that face tribes are costs and time associated with transportation to the institution or museum. Other obstacles exceed regulatory language.

Minor noticed the gap between the standardized regulations and the specific needs of individual tribes. There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to repatriation of tribal items.

She did not predict that she would receive such varying responses from the tribes she contacted. Some requested a space on campus where the tribal representatives could spiritually prepare before consulting with Minor. However, the SRJC museum does not have a dedicated space where tribes can perform spiritual ceremonies, which may include smudging or burning sage, before consulting on tribal belongings.

Other tribes might be satisfied with Zoom consultations, she said.

SRJC does not provide guidelines or support for this process. There is no campus committee with representatives from local tribal communities or others related to the museum to organize the process.

The funding for any NAGPRA-related labor, resources, or costs, like education and expert support, comes out of the museum’s budget. All of the work related to NAGPRA falls on the shoulders of the museum’s sole director/curator whose job responsibilities include, in addition to curating and preparing exhibits, maintaining the archives and collections, curriculum development and community outreach, marketing, fundraising, accounting and pest abatement. Ideally, the museum would have a dedicated staff member spending at least 20 hours a week on the repatriations, Minor said.

Community college museum directors or faculty managing tribal collections will not get staff, funding, or guidelines to individual colleges for the NAGPRA repatriations from the California Community Colleges Consortium.

“The California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office is dedicated to the long-term process of building collaborative relationships that foster educational equity, strengthen Tribal sovereignty and prioritize the needs identified by Tribes throughout California,” a letter provided by the Chancellor’s office by email said.

“It is imperative that the administration and faculty at any college still possessing items covered by these laws work together expeditiously with the appropriate Tribal officials to repatriate them,” the letter, dated Sept. 20, 2023, and signed by Sonya Christian, chancellor, and Cheryl Aschenbach, president of the Academic Senate, said.

“Ultimately it is up to locally governed colleges to comply with state laws that apply to the return of any artifacts to the appropriate Tribal representatives,” a spokesperson for the Chancellor’s Office said over email.

Another challenge to museums is the language of the ruling, which is “impenetrable,” according to Eric Stanley, deputy director and history curator of the Museum of Sonoma County.

Sometimes, museums and institutions leverage vague terminology in their favor. For example, NAGPRA defines one category as “culturally unidentifiable human remains.” Terms like this permit “archeologists, anthropologists, and directors, curators, to say, ‘Oh, well, we can’t identify this object. So since we can identify it and we don’t know, we can keep that,’” Flyswithhawks said.

The data ProPublica gathered in its multi-year investigation shows this. Museums and institutions use language – Western terminology – as a loophole to hold onto tribal ancestors.

Now, with strengthened language, NAGPRA returns authority to tribes. “Whoever finally named that and saw that – I’d like to shake their hand,” Flyswithhawks said. “This new regulation will help direct institutions to better rely on [and] defer to tribal nations. Our knowledge of our own customs . . . they are finally going to begin to acknowledge our customs, our traditions and, historically, who we are.”

Minor agrees. The updates now let her defer to tribes and indigenous tribal knowledge. It’s an opportunity for transparency, both Flyswithhawks and Minor pointed out.

The updates are necessary, according to Jonny Brouillard, SRJC student and co-president of American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES), Inter-Tribal Student Union treasurer, and M.E.Ch.A. treasurer and member of Second Chance.

“The wisdom of all cultures should be available for future generations to learn, and museums provide that source. So I’m all for a museum having a Native American display and a collection just for educational purposes. But at the same time, ethically, I do believe that it should be consensual,” he said.

The updates create the opportunity to further dialogue and collaboration not only between museums and tribes, but also between institutions. “That’s the best way to look at it,” Stanley said. “[It’]s an opportunity to have more of those conversations and more of those connections.”

These conversations may be uncomfortable.

“I think it’s only right and fair, especially given California’s dark history with the indigenous population of California and how much gaslighting went on throughout the generations,” Brouillard said. “It’s crucial to have communications and explicit consent from the tribes and or descendants of Native Americans of the Native American artifacts that are to be displayed.”

In the context of explicit and consensual consent, these conversations blossom.

The NAGPRA updates “offer a mechanism” to correct earlier mistakes, SRJC Multicultural Museum volunteer Ross said. At the museum, “we have responsible curators like Rachel who are working with the Native community actively for the various exhibits, and really trying to capture their voice, and center their voice, uplift their voice, and that’s the right thing to do. It’s not necessarily happening everywhere. But it’s happening here.”

The repatriation process is “the most important and rewarding work in my career,” Minor said. The process has created opportunities for “human-to-human” connections. Working through the museum collections helped her to connect with local tribes beyond just the NAGPRA regulations.

These conversations have resulted in local tribal members collaborating and developing new exhibits, including a current exhibit called “Roles, Rules, and Responsibility: Northern California Two-Spirit Weavers,” which features the work of Silver Galleto (Southern Pomo/Coast Miwok), Jarred Lincoln-Stremberg (Karuk), and Augustine Granados-Young (Maidu).

Despite the thirty-year glacial pace of reparations, Flyswithhawks sustains optimism. “I’m hopeful that there’s a way that academia and anthropologists can . . . listen to our people, our elders, our wives and our aunties and grandpas – listen to their stories,” she said.

She places hope in the space where tribal indigenous knowledge and Western science intersect. It is in “the intersectionality where we can help each other,” she said. Then, “what would happen – we call it ᎪᎯᏳᎯ or gohiyuhi – respect, if there’s this true respect for who we are as indigenous people, and where we come from – and that includes spiritually – ” then, and only then, can collaborative connections blossom.