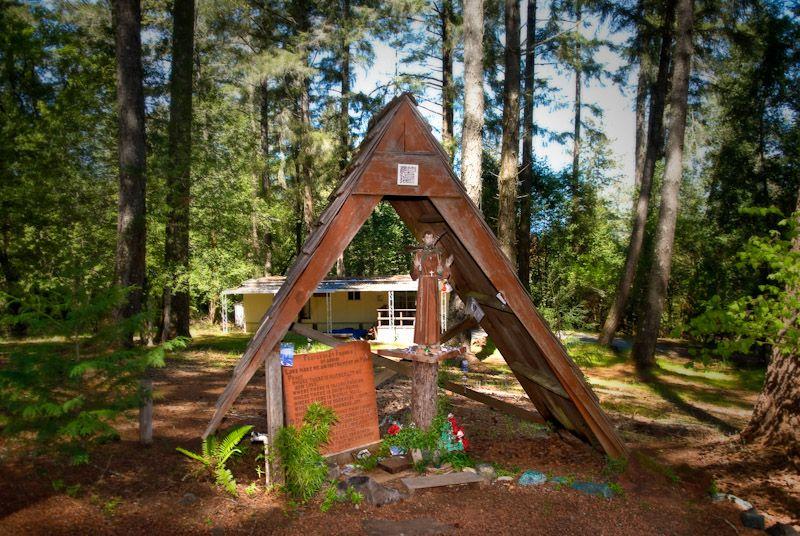

I woke up midafternoon at Azure Acres, an old hunting lodge turned into a rehabilitation center, hidden in the serene nature of Sebastopol. It was March of 2008. I was 19.

“OH f–k,” I cursed. I sat numb all morning in a single room looking out into the forest surrounding the rehab. The whole week before I was too sick to leave my room. I laid in my bed detoxing — shaking and sweating, puking up anything I ate and unable to sleep more than three hours a night, suffering from withdrawals from drugs and alcohol. Physically, I felt a little better and I decided to start participating in group therapy. I somberly walked my way to the room full of other people with the disease of addiction.

Barb, the counselor, assigned everyone to write about their feelings and share them with each other. This is what my melancholy, selfish self wrote; “The world is mute. I stare blankly at these other lost beings, in utter confusion. Escape is all I ponder. Wondering how I can, if I will. They say just swallow a pill. It’ll be better. Well I think I’m too sore. Torn, betrayed, alone, prone to destruction. That is my only way. I can never be just one. Contemplate life. Live to die. One day closer to nothing, nothing inside. Fake joy surrounds this hollow scene. Happy is a feeling I will probably never be.” I read this aloud and said I believe when I finish rehab there is no way I’ll stay sober. At 19 I thought life was better when numbing the pain.

Barb stared me in the face and said, “This is probably something you don’t want to hear. You’re going to end up dead like that friend you found a couple months ago.” Images of my friend Mikey, grey in the face, flashed through my mind. He died asphyxiating on his own vomit. I was the person who found his body in the apartment we shared with two other friends. It was a numbing, horrifying experience to witness a friend minutes after death.

I glared at the counselor, left the room immediately and ran into the forest where I screamed louder than I ever have. Looking back, I know I was suffering from PTSD and having a panic attack, unable to decipher my emotions. The other counselors came out to calm me down and sat me in the main office.

I raged about how Barb the counselor was a terrible person who should never speak of Mikey. I see now she was just being honest and trying to save me from future pain. But my fight or flight mentality kicked in. Stay at rehab and deal with my emotions — or run. I decided to make an escape. I stole my phone back from the office when they left me alone for a mere three minutes. In a completely numb and angry daze, I walked down the hill through the forest into a still torn world in my mind.

The sun sorrowfully setting in my face, I made it to the nearest highway, stuck out my thumb and hitch-hiked back to Santa Rosa. Mark, a traveling hippie, picked me up. He was on his way to Garberville to trim weed. I was under the drinking age at the time so I asked him to buy me a bottle of Jack Daniels. He did, and also gave me an Oxy.

He dropped me off at the corner of Guerneville and Vine Hill Road. Sitting down in the vineyards, I opened the bottle of Jack and began to drown my agony. Just wanting to erase the situation — my whole life —away.

I thought to myself: “Swallow this pill, down the pint, lay in the grapes, lose the fight.” At this point I was drunk as hell, laying in the vineyard. I looked up into the sky, my blurred vision focused in on the grapes above me, and in a moment of lucidity I saw hope and beauty in nature. My survival instinct kicked in and I didn’t mix the pill with the alcohol, which could have been deadly.

I put out my thumb again and hitched another ride. This time the driver took me all the way into Santa Rosa and dropped me off close to downtown. I walked to the house I was staying at before rehab. My two former roommates, Luna and Sara, were shocked to see me and worried after I told them what happened. Spending the night there, I drank more and buried the issues deeper. The next morning I called my aunt to pick me up and returned to rehab. I finished the 30-day stay at Azure Acres but had no desire to change. When I left I used for another seven years.

On July 13, 2014, I was arrested for a third DUI. My choices were to be incarcerated for 120 days or participate in a year-long, out-patient court treatment program. I chose the court treatment program. I must go to court once a week, call to listen for an assigned color for random drug and alcohol testing everyday, attend three or more Alcoholics Anonymous meetings a week, and participate in group and individual counseling.

In the first few months of the court program I didn’t take it seriously or follow the rules. I smoked marijuana and my mandatory testing program detected it. The repercussion of using is to go to jail for a week — so off I went to sit inside a cell, compare myself to the other criminals and gloat to myself I wasn’t as bad as the heroin addict on the other bunk. When I was released from jail I still didn’t digest the severity of what I was going through. I tried to manipulate the program and thought if I drank after I had drug tested a few times during the week, they would not find out. I drank one evening, lost control and blacked out. The next morning my testing color was called – another week in jail to sit and think about my decisions. After being caught for marijuana and alcohol, I figured I would switch seats on the Titanic and use nitrous oxide — also known as whip-its — since it is undetectable through testing.

At first my use of whip-its was every other day or so. I thought, “I’m not an addict. I can control this.” Even with all the obvious evidence of addiction in my life, I still needed to find a new mind-altering substance to switch to. It wasn’t enough yet to realize that I have a problem. My denial was strong and I wanted to beat the truth. My use progressed rapidly. Within three weeks I spent entire days, morning to night, draining oxygen from my body and neglecting life. Everything I touched in these few weeks became even more unmanageable as my powerlessness against whip-its grew.

But my last time down the rabbit hole, something happened. A sober friend of mine called me. I told him I was using and he could not come over to my apartment, but he insisted because he could hear in my voice that something was wrong.

When he walked in, my face was discolored and my lips where blue from oxygen deprivation that day. He called my sponsor and informed her of what was happening. She showed up and asked if I was willing to throw away the drugs. Then a miracle of sorts — clarity, an epiphany, incomprehensible demoralization at its finest occurred. I realized that, if I continued using and draining oxygen at this rate I was going to asphyxiate myself. I made a decision as I began to worry every other breath about how insane I was acting. I looked up at the two people there to help me and my mind switched. I threw the rest of the whip-its away. That night my sponsor left me with a saying that would change my life. She said, “If nothing changes, nothing changes.”

If I had died the same way as Mikey, it would have been tragic. Thinking of putting anyone else through that pain woke me up. I couldn’t forgive myself. For what I denied when I found him, I later found in myself. A desire to change took effect when I admitted to myself I have a disease I could die from. I accepted that using drugs and alcohol is not an option for me. That realization is a stark reality now.

The world is not out to kill me or any of my friends, but the choices we make are. I have the disease of addiction, but it’s treatable and many people do recover. Today I have a choice, and I choose to be sober. Healthy fear can bring about positive changes. If a problem exists in life, it will worsen until I find a solution. I’m fortunate to be around to enjoy a new way of living, free from the bondage of drugs and alcohol that were once my answer to any type of grief or problem. Now I use healthy coping mechanisms that won’t lead me to rehab, jail — or most importantly, death.