“I’m sorry,” said the female voice on the phone. “He’s not going to get better from this. We give him about six months.”

I thanked her for the call and hung up. I sat there for several minutes in silence until Mom and her wife came and hugged me as hard as they could. I didn’t cry.

It’s been seven years since I received that call. Seven years since my dad succumbed to bladder cancer and died about a week later. I still haven’t cried.

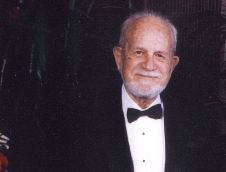

I was not surprised by the news. After all, Jack Randolph was an old man, already in his 60s when he married my mom. By the time I received that call, he was 86 and had been a chess master, a barbershop director and a pilot. He had, by all accounts, led a long, full life. He wasn’t in bad health before the diagnosis — but he, every friend, family member and I — knew something was going to happen to him, and it would happen soon. It was expected, and for the most part, accepted.

My dad and I got along famously. He was kind, sweet, loved to spoil me and for the most part let me do whatever I wanted. After my parents’ divorce when I was 11, visiting his house was a kind of a mini-vacation. I grieved, but between my acceptance and my good memories, I had little reason to cry. I still don’t.

That doesn’t mean I don’t regret.

He was the youngest child of a massive amount of brothers and sisters, and I regret never learning their names or how many there were. I regret that I don’t know his mother’s or father’s names, where he grew up or what his high school was, when he got his pilot license or how he became a chess master. I learned most of these things from family and friends, but never spoke to him about them. Dad rarely brought up his past.

It was hard to talk to him, quite literally, as he was deaf. He went deaf long before I remember, but it was still pretty late in his life when it happened. This meant, among other things, that he was completely tone deaf. I never got to hear him sing like he used to, something that bothers me more than I can say. More importantly, talking to him was a struggle. He could still speak perfectly fine, thank goodness — but he couldn’t hear you coming, or modulate his voice, and he never learned to compensate for his deafness. Learning sign language isn’t nearly as helpful when the person you’re learning it for barely knows it himself. I didn’t go out of my way to avoid talking to him, but long conversations were a chore for us both, so they never happened.

One would think that a person’s imminent death would change that. One would be wrong.

I had seen people get sick and go to the hospital before. But it’s different knowing that he’s never going to get better; he’s only going to get worse until he dies. I didn’t want to deal with that, so I stayed in my room and let others help him use the bathroom and work out which pills to take. I watched an old movie with him, and he fell asleep halfway through, but I didn’t really talk to him. I stayed in my room and watched YouTube and tried to ignore his limbs gradually wasting away into sticks.

His smile was the last I saw of him, when they carted him off to a rest home. Well, no. Technically the last I saw of him was when I went to see his dead body a day or so later – I still don’t know if that was a good idea – but by that point Dad had vacated the premises, so his smile was my last sight of the real him.

They say when you look back on your life, what you regret most are all the things you didn’t do. They should add that the same holds true when it’s someone you care about. I was there for him, but there are a thousand little details that I’ll never know because I thoughtlessly never asked for them.