In the chilly late-morning of March 1, 2023, the students and staff of Montgomery High School experienced a tragedy that shook their community to its core.

Just after 11 a.m., Jayden Pienta, a 16-year-old junior, along with another student entered an art classroom to confront freshman Daniel Pulido. The confrontation quickly escalated and turned violent.

During the struggle Pulido, 15, stabbed Pienta three times. Teachers and staff rushed to break up the fight.

As students escorted Pienta to the school office, another scuffle broke out. Pulido fled the scene and escaped from campus.

The Santa Rosa Police Department responded and cleared the campus of any remaining threats. Paramedics were then allowed onto campus to attend to Pienta.

Paramedics transported Pienta to Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital. He later died from his wounds.

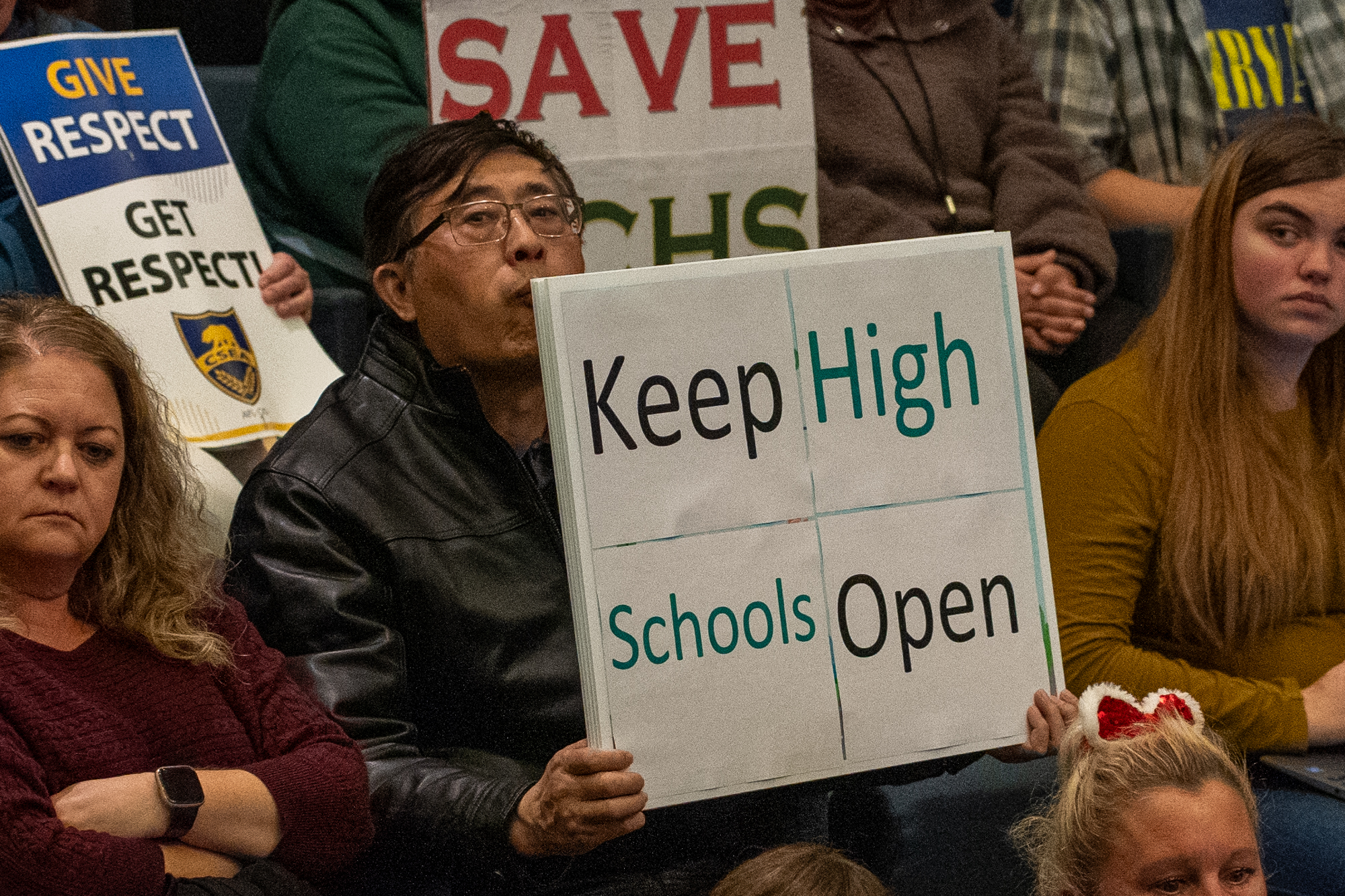

Shocked by this tragedy, a debate ensued amongst school board members, parents, staff and students over returning School Resource Officers (SRO) to campuses.

Supporters of SRO programs emphasize benefits such as positive relationships with students and quick response times to emergencies, while critics of these programs claim that a police presence on campus is a powerful institutionalizing force on minority students.

Santa Rosa is not the only city grappling with these issues. The question of police officers on campuses is a microcosm of larger conversations taking place across the nation around appropriate and effective ways to keep communities safe.

Police On Campus

SROs are police officers who patrol school campuses. Their primary job is to prevent and respond to security threats, but they also often act as liaisons between students and local police.

According to a 2019 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 78.6% of funding for these programs nationwide came from school districts, while the rest came from police departments and federal grants. These numbers, however, vary widely.

Officers were first introduced to campuses in the United States in the 1950s. SRO programs rapidly expanded in the late 1990s partially due to federal incentives and the first mass shootings on school campuses appearing in national headlines, according to the American Bar Association.

By 2018, 46.7% of public schools in the United States had law enforcement officers on campus, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Santa Rosa City Schools (SRCS) first established an SRO program in 1996. The program started with officers splitting time between three campuses. After the shooting at Columbine High School in 1999, the program expanded to the rest of SRCS.

The SRO program at SRCS evolved and grew for over 20 years without outspoken public comment on the presence of officers at schools. Not all Santa Rosa residents, however, had a positive view of police on campuses.

“It’s a misuse of resources that could be going to therapists and social workers,” said Rafael Vazquez Guzman, Santa Rosa Junior College professor of humanities and religious studies. “Police officers are being used to try and pressure children into basically snitching on themselves, and not protecting their individual rights.”

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, Guzman migrated to the United States at 15. He’s the founder and executive director of Líderes del Futuro, a nonprofit that helps immigrants and refugees from Latin America and conducts research on the experiences of local high school students.

Guzman thinks that police presence on campus is a way for schools to circumvent student’s rights. He has spoken to students who claim that, instead of honoring their requests that their parents be present, administrators used SROs to question and intimidate them.

“People of color specifically often have negative experiences, and are more likely to get arrested,” Guzman said.

The nature of this relationship between police officers and students is central to the debate.

According to an Oct. 2016 report from the American Civil Liberties Union of California, on average students of color are 1.3 times more likely to be referred to a police officer than white students.

While opponents of SRO programs, like Guzman, see these interactions as combative, proponents argue that high school campuses are the best place to build positive relationships between students and law enforcement in their communities.

According to SRPD Public Information Officer Sergeant Patricia Seffins, local police strongly support these programs.

“It’s a great way to prevent crime on campus when students have officers that they know and trust and can go to,” Seffins said. “They’re more likely to provide them with information that can help officers intervene in situations before something significant happens.”

She added that the local police are very aware of the concerns some community members have about SRO programs and emphasized that their goal is to create a solution that everyone feels comfortable with.

SRCS Board of Trustees Removes Officers from Campuses

When Omar Medina was first elected to the SRCS Board of Trustees in 2018, he noticed the memorandum of understanding (MOU), or contract, between the SRPD and SRCS was troublingly vague.

“The MOU that existed had no details, nothing about operating,” Medina said. “It was just like a general contract that said [the police] are here, but there was nothing about who does what, who’s responsible for what. So a committee was established to review the program.”

Medina, now president of the board, graduated from Elsie Allen High School in 1996 as part of the school’s first graduating class. He is an outspoken critic of law enforcement on school campuses.

In June 2020, amid a tense cultural moment regarding institutional racism in the United States, Medina posted an argument to his Facebook page detailing why he strongly opposed SROs on campus. The post cited multiple instances where members of BIPOC communities experienced harassment at the hands of police, as well as the history of police presence at schools in California.

Later that month, on June 24, 2020, a motion was brought to the board to pause the SRO program while it was reviewed by a committee and the contract was updated. The motion passed unanimously.

“There was no mechanism or protocol to collect data of the contacts on what types of interactions police were having with students,” Medina said. “The other thing the committee found is that teachers and staff were overusing police in situations where it shouldn’t have been the SROs doing those things, it should have been the staff.”

Medina also cited comments made by officers during SRCS board meetings as causes for concern.

“Some of the things that some of the officers said made us say, like, ‘Woah, these are the people that are working in our schools?’” Medina said.

In December of that year the board of trustees sent a letter to Santa Rosa City Manager Sean McGlynn.

“We wanted to meet with [the city manager] to talk about changes and to bring healing, because this was in the context and time of the George Floyd stuff that had happened, I believe, in May of that year,” Medina said.

The letter to McGlynn, which The Oak Leaf obtained from Medina, stated that 8% of students, particularly students of color, who responded to a survey indicated negative or fearful reactions to law enforcement on campus. Additionally, the letter stated, “the trustees were in agreement that a partnership with Santa Rosa City and SRPD would be desirable to create a model for safety for students/youth.”

The city manager never responded to the letter and a new contract was never established, according to Medina.

In 2022, Maraskeshia Smith was appointed city manager, and John Cregan became chief of police. Medina cites this turnover as another reason why the conversation over re-establishing an SRO program between SRCS and the city continued to lay dormant until the first day of March 2023.

Student Led Change

Lyla Snyder, a senior at Montgomery, was in her third period class when the fatal stabbing occurred.

“I still remember the sound of the police running down my hallway and yelling,” said Montgomery senior Lyla Snyder. “We were in that classroom for three to four hours with no sense of what was going on. The only sort of information was coming from students texting each other. I will never forget the complete sadness that fell over the student body at Montgomery that day.”

Snyder, 18, founded a student group on campus called Student Led Change (SLC) in the wake of the fatal stabbing. She supports SROs on campus.

“I noticed that students wanted a change in school safety, but had no outlet to do so,” Snyder said. “So I began Student Led Change to bring together a community of students who could fight for what they individually want, rather than focusing on one opinion overall.”

Following the stabbing, in the summer of 2023, three SRCS board members, Mayor Natalie Rogers and City Councilmembers Dianna MacDonald and Jeff Okrepkie, formed a committee to collaborate on the future of the SRO program and other issues facing SRCS, according to Medina.

SRCS board members on the committee included Medina and Trustees Alegría De La Cruz and Jeremy De La Torre.

On Dec. 10, 2023, due to a recent spike in violent fights on campuses, SRCS Superintendent Anna Trunnel placed police officers on campuses for the remainder of the calendar year, according to reporting by the Press Democrat. This was the first time since 2020 that officers had returned to campus.

Two days later, at a SRCS board meeting, SLC presented data from a recent survey that students had conducted at Montgomery. While the survey reported respondents of roughly a third of the student body, the results showed overwhelming support for returning officers to campus.

“The presentation was to show the board of education the data they have been asking for,” Snyder said. “We were tired of our voices being ignored because of our opinion on campus safety. So it was an opportunity to show the board of education our knowledge on the matter.”

That night the board voted 5-2 to pass a motion to allow exploration and implementation of an SRO pilot program at SRCS in cooperation with the City and SRPD.

Recall Attempt

In March 2024, little more than a year after the stabbing at Montgomery, Santa Rosa City councilmembers announced that the SRO pilot program would not be ready for the beginning of the new school year.

That same month Safe Campus Alliance (SCA) filed to recall Medina.

Melissa Stewart, a parent of two students at Montgomery, is the co-founder of SCA.

“As a parent I was really confused,” Stewart said. “The district wasn’t very transparent about what they were going to be doing at our school to help with school violence and gang activity. So we were thinking we were either going to see SROs on campus like we saw in years prior, or if it would be more campus supervisors.”

However, by the start of the ’23-’24 school year, there were actually less campus supervisors, according to Stewart.

“I can’t even tell you how many fights, it was just bad,” Stewart said. “And videos of the fights were being posted online, and staff were being knocked down trying to break up fights. So I reached out to parents that I thought would be interested in sharing information.”

Stewart held a meeting of a group of concerned parents at her business in Santa Rosa.

“In those conversations we got a lot of information, and we realized there were so many parents who were just as concerned,” Stewart said.

The group had to find a larger space to hold their meetings as the attendance level continued to grow, according to Stewart.

The group grew large enough that it began breaking up into committees, though the main goal remained school safety. Conversations within the group centered around the SRO program, which SCA supports, though not all members are in favor of officers on campus, according to Stewart.

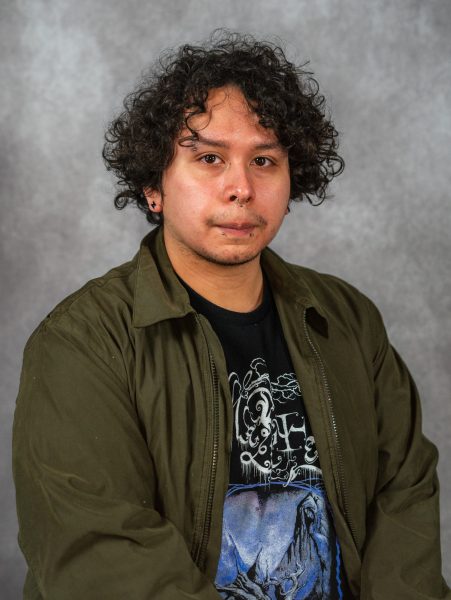

Manny Morales, a staff member for the North Bay Organizing Project and the youth organizer for the Sonoma County Latinx Student Congress, has worked for the last four years with high school and SRJC students as a restorative justice specialist, supporting students through restorative dialog and conflict resolution.

“Our definition of safety wasn’t necessarily centered on more security,” Morales said, describing his vision for safer schools. “It was centered on student wellbeing, having more supervision, more support on campus and added resources.”

Morales is against SROs because he feels programs tend to push students to the margins. In the past, the partnership between schools and the police department put students at risk of receiving gang-related enhancements, causing a cycle of systemic distrust, according to Morales.

“It’s not an anti-police stance. It’s a criticism of how police function, in particular interacting with young people of color, students, students with disabilities and LGBTQIA+ students,” Morales said.

While opposed to SRO programs, Morales was sensitive to the concerns of the parents who supported them. “It’s their response to what they perceive as an urgent situation,” Morales said. “But I think the sense of urgency also kind of informed why they wanted to call for the return of police officers.”

Rebecca Sullivan, a health technician at Montgomery and co-founder of SCA, has a child who attends Montgomery. In her tenth year working at Montgomery, she doesn’t feel the staff is properly trained to respond to violent incidents on campus.

“We are not trained to help break up fights or deal with someone with a weapon,” Sullivan said. “We’re just not equipped. These are the times we are living in now, where it’s easier to get firearms, easier for students to carry weapons with them, and our safety plans are not catching up to the local crime and violence that we’re experiencing.”

Sullivan was one of the staff members to tend to Pienta while she waited for paramedics to arrive. She feels the incident would not have been fatal if SROs were present, pointing to officers’ ability to use positive relationships with students to preemptively stop violent situations.

Additionally, Sullivan feels the response time for first responders to violent incidents on campus can be much slower as the police must first clear the campus of any threats before paramedics can enter the campus.

As time went on and the SRCS Board of Trustees weighed the options for the future of school safety, the parents within SCA became frustrated with the lack of action by the board. Stewart points to a lack of transparency and willingness to have a conversation around these issues as a cause for the delay in addressing these concerns.

“I think some people that voted for it did have an intention of having a pilot program,” Stewart said when asked about the SRCS board’s vote to begin developing an SRO pilot program. “And I think a lot of people on the board, that was their way of getting us to stop coming to meetings. But we were very cautiously optimistic that it would happen.”

According to Stewart, her optimism faded over time. She points to a meeting Medina held with the Montgomery student council as the tipping point of hope that he would listen to the concerns of parents, students and staff.

The meeting propelled Stewart, and the rest of SCA, to attempt to put a recall Medina on the November 2024 ballot. The campaign was ultimately unable to come up with the 2,709 signatures needed.

While SCA felt that the blame for the slow process of returning officers to campus should be cast toward Medina, the president of the board pointed to a few different reasons as to why the program has taken so long to be rolled out.

“There were some issues that Alegría and I have had with some of the specifics in that MOU that we haven’t fully resolved,” Medina said about the draft created by the 2020 committee. He added that, while the committee was mostly in agreement, there are some unresolved issues to sort out.

Medina also explained that the departure of former SRCS Superintendent Anna Trunnell at the end of the ’23-’24 school year set the process back as the committee had to familiarize her replacement with the current situation.

When Trunnell left, the committee lost some of its direction.

Medina said he took on the role of bringing the committee together to continue their work on the pilot program and MOU but hasn’t been successful in his attempts.

“The other complication that has occurred is that the people that are on this committee, city council folks and school board members, are all extremely busy so oftentimes finding a date that works for everybody is very difficult,” Medina said. “The last attempt that I made we couldn’t get a date that worked for everybody and since that attempt, I haven’t tried again.”

While the committee’s next meetings hang in limbo, Medina said he has spent time working on the current MOU. Though he notes that he still has more to look over and finalize before bringing it to the committee for review.

“So I mean, if it’s me, sure, but I don’t see anyone else taking the initiative,” Medina said.

Ongoing Issues

In the nearly two years since the fatal stabbing at Montgomery, multiple instances involving violent fights or weapons have required police response to SRCS campuses.

On Aug. 30, 2024, just two weeks into the school year, another student stabbing occurred, this time at Elsie Allen High School.

This school year two loaded guns have been found on campus at Montgomery and one found at Elsie Allen.

Paige Warmerdam, a special education teacher at Montgomery, supports bringing SROs back to campus.

“They become kind of part of your school community,” Warmerdam said. “I believe that helps deal with some of the things that are happening outside of the school that kind of get pulled into our smaller little microcosms and become a problem, like gang violence.”

Warmerdam, now in her 25th year at Montgomery, does feel her school’s safety has improved this year and points to more adults on campus as a key factor in the improvement.

“We’re actually fully staffed with campus supervisors,” Warmerdam said. “I believe there are five now, which before they were maybe operating on one or two.”

Those campus supervisors are positions the district now calls student safety advisors. Medina also points to their presence as progress towards safer campuses without the presence of law enforcement. However, he does feel that it is still not enough, and fears these positions may go away due to budget cuts expected in 2025 to address the district’s $20 million deficit.

“The need and what we can do are difficult things to meet because of funding,” Medina said.“We will have a meeting of potentially the numbers of staff we might need to cut, and those are some of the positions that we need to cut because of a huge deficit in funding.”

The board is not only considering staffing cuts but also potential school closures. Many are worried about what those closures could mean for campus safety.

“Our district is at a critical juncture,” Dr. Daisy Morales, the SRCS superintendent, said during the SRCS Special Board Meeting on Nov. 20. “We face a critical need to make significant reductions to maintain solvency. Sadly, it’s not if we close schools, it’s when we close schools.”

Those who support SROs returning to campuses and those who are in opposition are similar in at least one way: They both want a safe environment, but are likely to continue to be hampered by Santa Rosa’s financial woes and citywide management problems.

“I don’t need police officers. I need therapists and I need social workers,” Guzman said. “Promote mental health, do all that work, that’s what is needed, not somebody in school who is going to intimidate people of color simply by being there.”

In Melissa Stewart’s eyes, continuing the conversation is key to finding better campus safety.

“Nothing is going to change if we don’t have a conversation,” Stewart said. “We’ve always been very welcome to it; we care about these students. I don’t want any students of color to feel targeted, that’s definitely a value to us.”