Public trust in news reached its lowest point since 2016 when Donald Trump became president, according to a Gallup poll in September 2023 and it continues to decline, a worrisome problem in general and especially so in an election year. So how can journalists regain the trust of readers bombarded with fake news, social media fantasies and political farces?

Show up, says Katherine Corcoran, author of “In the Mouth of the Wolf: A Murder, a Cover-Up and the True Cost of Silencing the Press.” Go to city council meetings, rub shoulders with locals, listen to their needs. In other words, journalists need to engage meaningfully with the community they represent in their stories.

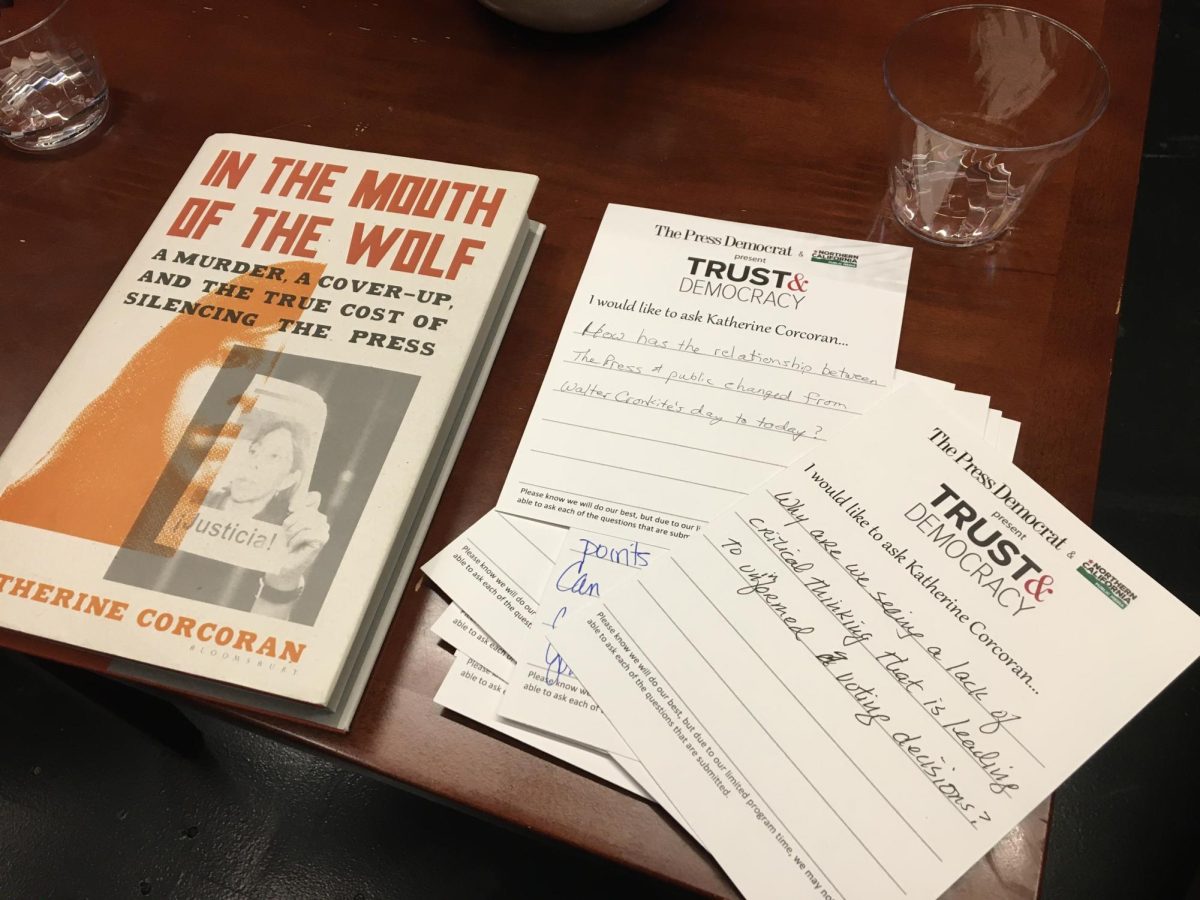

Corcoran was the guest speaker at the Press Democrat Journalism Foundation’s inaugural “Trust and Democracy” community conversation held in Santa Rosa Junior College’s Frank Chong Studio Theater on March 13. The event, held in partnership with NorCal Public Media, aims to engage the community in a dialogue about the role of journalism in a democracy.

Corcoran, former Associated Press bureau chief for Mexico and Central America and former co-director and professor at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism, spoke about her experience investigating the murder of Mexican journalist Regina Martínez.

Following a brief introduction to her 2022 book, Corcoran engaged with Press Democrat Senior News Director John D’Anna in a wide-ranging conversation that began with Corcoran’s early years as a reporter, to her experience reporting the Martinez murder and her thoughts on the role of local news in today’s political and social climate. Afterward, Corcoran answered written questions submitted by audience members during the conversation.

I just wanted to be a DJ

Corcoran did not set out to be a journalist. “I was just a lazy liberal arts major with no idea of the future,” she said. But she did want to be a music spinner on a radio station, which was a difficult job to get. She thought if she got a radio news job, she could “maybe sneak over into the music side.”

So she walked into the college newsroom and asked for an assignment. She described the news team as “indiscriminate.” They said to her, “Oh, you’re here. Okay, here. Here’s an assignment.”

Corcoran covered the assignment, wrote the article and saw her name on the byline the next day. “I was hooked. I forgot all about radio.”

Local news is the future

After graduating with a bachelors from the University of Notre Dame, Corcoran worked as a journalist in local newspapers, including the Tempe Daily News, the Denver Post and the San Jose Mercury News.

Corcoran described how she started out as a journalist working at the Tempe Daily News where “you really felt the connection the community had with its local newspaper,” she said.

People would say “Oh, we’re glad you’re here.” Or maybe, “You guys always mess everything up.” Regardless, there was always conversation. Because there was no internet, “people would write us letters . . . [they] would come into the office [with] story ideas,” she said.

Corcoran built on this theme of trust-building in the press-public relationship throughout her conversation with D’Anna.

Especially in an era defined by nearly instantaneous mass media content production, rebuilding trust between news outlets and their public must take place at the local, human-to-human level. Trust develops through individual journalists representing and writing for their local communities each time they show up at city council and school board meetings, baseball games and community bake sales to tell stories and give voice to community issues.

At the same time, communities need to support their local media. A devalued or under-supported newspaper risks becoming obsolete, leading to news deserts, or places where newspapers have gone out of business.

D’Anna drew a direct parallel between communities that lack a local news source and the areas in Mexico where journalists have been killed or silenced. A recent Pew Foundation survey found that in these news deserts “the level of government corruption has risen dramatically, and the level of civic engagement has decreased dramatically,” he said.

“What happens to everyday people when you silence the press?”

When Martínez was murdered on April 12, 2012, she was one among more than six journalists killed in Mexico that year. At the time, Corcoran worked as AP bureau chief for Mexico and Central America. She knew of Martínez and had tried to hire her to report for the AP.

These murders and other attacks on journalists created a ripple effect in the journalist communities throughout the Mexican states. They had a “tremendous” effect on local journalists who lived, raised families and worked with colleagues who had been attacked, Corcoran said. Journalists self-censored or left in exile rather than risk the intimidation or attacks, resulting in “zones of silence,” Corcoran said.

In the zones of silence, levels of corruption rose.

What struck Corcoran about these murders was that the journalists were reporting on everyday crime, not high-profile stories about powerful people in their communities. But neither the Mexican government nor the international community were doing anything about it. “At least if I just wrote about it for a wider audience, for an international audience, that would be a way to expose what’s going on and maybe bring about some kind of help or solution,” she said she thought at the time.

Martínez was a journalist known for digging into complicated and controversial issues in the Mexican state of Veracruz. She reported on government corruption, human rights abuses and the tangled web of government and organized crime. Unlike some journalists, she could not be bribed.

On April 12, 2012, a neighbor found Martínez’s body. She had been beaten and strangled in her apartment. According to the official narrative, Martínez was the victim of a “crime of passion,” killed by a disgruntled lover.

Corcoran’s investigation uncovered layers of lies that government officials promoted in an attempt to cover up Martínez’s murder.

In her book, Corcoran tells Martinez’s story through the voices of her protégés, three cub reporters Martínez mentored. In part two, Corcoran narrates her journey to investigate the murder, a twisting path that led to frequent dead-ends and detours.

Through the 10-year process of reporting and writing her book, Corcoran witnessed the effect of violence and intimidation on Mexican journalists. Several of her sources had to hide in other Mexican states or Central American countries; others left journalism altogether.

In the intervening years, the death toll of Mexican journalists continues to rise. American journalists, like Wendy Fry and Alejandro Tamayo, continue to cover these murders.

The job of a journalist

Another purpose for writing her book was to showcase the bravery of the Mexican journalists who earn very little, she said. Additionally, the Mexican journalists didn’t have support from their own newspapers, a parallel to the current news landscape in the U.S., she said. “It’s not a profession that’s very inviting right now, given the financial circumstances, but it’s so important.”

A third purpose, among many, for writing the book was to show what journalists do.

In her book, Corcoran documented her dogged pursuit of the truth about Martínez’s murder. By pushing back on officials who dodged questions, doctored documents or disappeared witnesses, Corcoran strove to expose how the government attempted to obfuscate who killed Martínez and why.

From shining a light on political corruption to speaking up on behalf of community members demanding a stoplight at a busy intersection, a journalist amplifies individual stories to effect community-wide change.

We need to build trust through transparency

Among the questions submitted by audience members was how the relationship between the press and the public has changed since the days of Walter Cronkite, known as “the most trusted man in America.”

It is no secret that public opinion of the news has declined since Cronkite’s era. “Unfortunately there is a very high level of distrust,” Corcoran said. But the news-scape has changed drastically from that era of few news outlets to today, where news proliferates exponentially and the public is bombarded with fake news. To combat the misinformation, journalists must show their methods.

“I think we need to do a better job of explaining who we are and what we do and show what we do,” Corcoran said.

“My favorite is when a media organization does an investigation and they publish all their source materials along with the story so you can see the documents, you can hear the interviews,” she said. “We need to do more of that and to distinguish ourselves. We’re not perfect, we make a lot of mistakes too. And I think we need to own up to that.”

Engaged journalists also need the support of their readers

At the end of their conversation at the “Truth and Democracy” event, D’Anna asked Corcoran to read from her book. The passage he chose clarifies the parallel between the attacks on the press in Mexico and the developing attacks on the press under Trump.

“At the time I was in Mexico, I watched from afar as the concept and importance of truth deteriorated in the United States,” Corcoran said. She continued, reading from the final pages of her book, “And the first steps in shattering our notion of common standards of truth as a society in a democracy came in the form of attacks on the press.”

Since 2017, there have been over 1000 assaults on journalists according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. In addition to attacks on journalists, the site tracks intimidating incidents, like searching, seizing or damaging equipment, denying access, and serving subpoenas to journalists.

She closed her book with an impassioned plea for readers to support the free press, support that begins at home with the local newsroom. In exchange for journalists to be “the reliable counterweight, the trusted public voice” for the public, the public must, in turn, support the free press.