During her talk “Radical Women in the Burned Over District: Antebellum Religious, Racial and Gender Challenges Along the Erie Canal,” esteemed historian Anne Donegan lectured attendees on the power of unity between socially outcast groups clamoring for recognition and equality.

Held as part of Santa Rosa Junior College’s Women’s History Month lecture series, “Radical Women” recounted what is known as the Second Great Awakening, “a zealous wave of religious activity that led to the creation of not only new religious groups but also fueled many reform movements,” according to Donegan.

The awakening happened first with mostly middle-class women in Protestant and Quaker congregations in the rapidly industrializing communities along the Erie Canal in Upstate New York, the fastest growing part of the U.S. before the Civil War. The area was a center for religious, reform and radical abolitionist movements, with middle-class white women at the forefront and a diverse group of people alongside.

“Religious activity in this country is like a roller coaster; we’re really into it and then we’re not. But once we get into the 1820s we start to see that fluctuate back up, led by these middle-class women. What this leads to — as more women start going to church — is something called The Great Awakening, ” Donegan said.

Due to patriarchal norms, middle-class women were expected to stay home to raise and tend their families and be reliable churchgoers. But the sermons these women heard every Sunday did not uphold the standard; they were downright radical for the time.

The sermons challenged norms. They deemed drinking alcohol and slavery as sins, and eventually some movements called for abolition all together. Figures including Frederick Douglas and Sojourner Truth followed these sermons closely.

“[Truth] definitely went to a lot of these religious services [after she’d gained her freedom],” Donegan said, “and she believed not only that slavery is a sin, but also that women’s inequality was also a sin.”

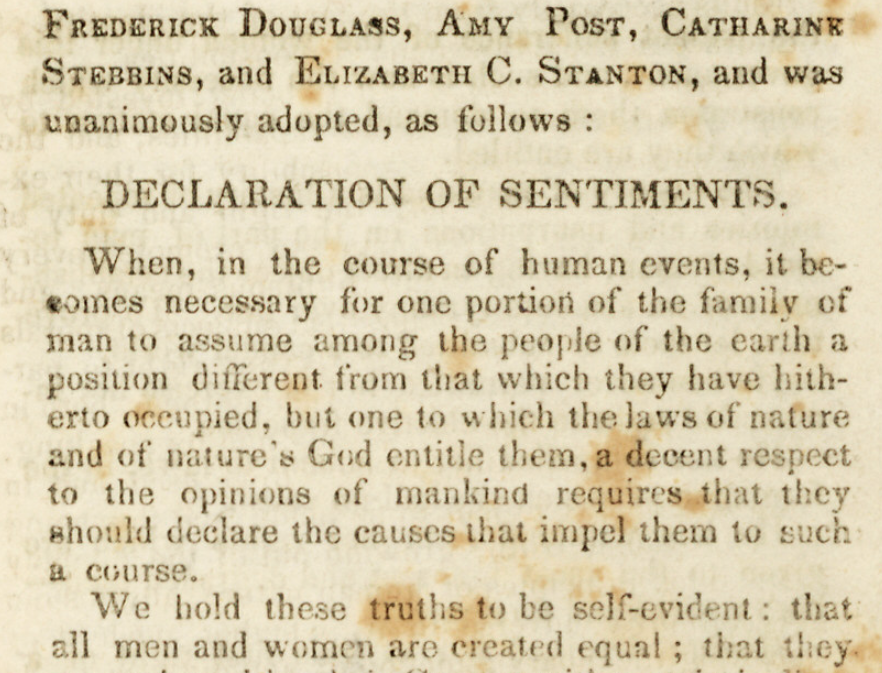

Although the fight for equality revolved around middle- and working-class white women, solidarity among the socially disparaged expanded the fight for equality and abolition. This union ultimately culminated in the first women’s rights convention, held along the Erie Canal in the movements’ hotbed, and featured Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s publication of “The Declaration of Sentiments.”

“In this document they talk about the tyranny of men over women,” Donegan said. “We see this laundry list of grievances of ways to lead to equality.”

The Declaration of Sentiments used the Declaration of Independence as inspiration but rewrote it to read, “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men and women are created equal.”

Frederick Douglass is listed on the declaration as supporting the cause.

To watch the full lecture, click here.