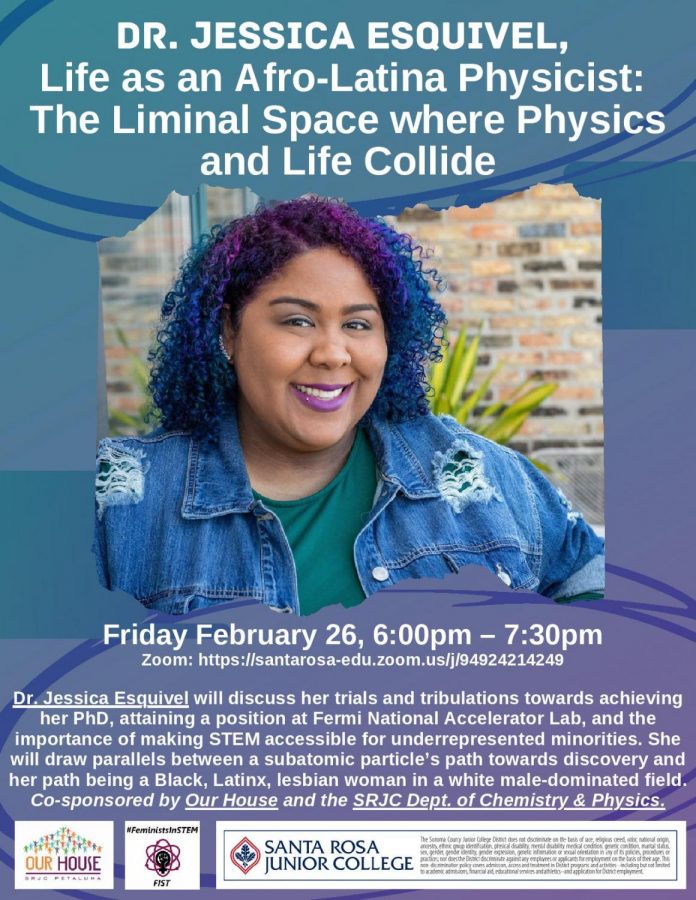

Jessica Esquivel encouraged inclusivity in the sciences and drew parallels between her life as an Afro-Latina physicist and the transformation of particles in a particle accelerator during her speech Feb. 26 at Santa Rosa Junior College’s last Black History Month event.

Esquivel, who has her doctorate in physics from Syracuse University, stands out in her field for multiple reasons. As a lesbian Afro-Latina in predominantly white-male dominated field, Esquivel conducts complex research at Fermilab, the United States’ premier particle physics laboratory. She studies the minute yet powerful forces that exist around and within us, work that helped researchers find part of a neutrino, a subatomic particle present everywhere but incredibly difficult to track due to its miniscule size.

Despite her own achievements at the highest levels of physics, Esquivel knows she is the exception, not the rule. She faced extraordinary disparities on her journey in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) field.

The National Science Foundation says women comprise only 20% of physicists, and according to Esquivel, only 2% of physicists are Black. About 150 African American women in the U.S. have a doctorate in physics or a physics-related field, according to African American Women in Physics.

During her talk, Esquivel told the story of her path through higher education as though she were a particle, an electron for example, traversing a particle accelerator, the specialized equipment she uses in her research.

She compared her youth to a particle itself, small and the basis on which everything is built. Raised by a single mother in Texas, Esquivel’s family encouraged her to pursue her dream to become a physicist after she was inspired by Jodie Foster’s character in “Contact,” a 1997 film about a scientist searching for extraterrestrial life.

She said her undergraduate years reminded her of a particle traveling through an accelerator’s target, where it overcomes barriers and is transformed. At St. Mary’s College in San Antonio, Esquivel double-majored in applied physics and electrical engineering. Despite professors’ discouragement to follow that academically daunting pathway, she persevered and graduated in four years. One advisor’s support had the same effect on her education as an accelerator’s focusing horn has on particles; the device funnels high-energy protons into a sharp beam capable of hitting a target.

After a gap year, Esquivel began graduate school. When obstacles got in her way, she felt as though she was in particle decay, slowly breaking down; she faced imposter syndrome and doubted whether she belonged in her field. But learning just how few Black women become physicists gave her the push to continue.

She describes arriving at the end of her studies as if she was encountering the accelerator’s absorber, the place where particles slow down and deposit all their remaining energy. After earning her doctorate, Esquivel was finally free to throw herself into her own work.

Of course her education was challenging in its own right, but she felt it was complicated by her identity. Esquivel’s gender, race and sexual orientation put her squarely in the minority and made her question whether she belonged in her field. She started to research ideas including stereotype threat, hyper invisibility/visibility and implicit bias. Her findings exposed that she was not the problem.

“I realized that there was language to describe how I was feeling. I realized that I wasn’t the only one that was feeling this, that it was not an issue with me but it was an issue with the institution,” Esquivel said. “There was a problem with the way the system was built to make me feel the way that I was feeling. It was an issue with the culture.”

Support from her family, colleagues and friends with similar backgrounds helped her overcome feeling like an outcast. They helped her recognize her value as a lesbian and Afro-Latina in these scientific spaces. The doubts she had were not uncommon, but they took her brain-power away from her goal of becoming a physicist.

Today, as physicist at the country’s premier physics research site, Esquivel not only contributes to the science canon, but hopes to lift-up future generations. She encourages minorities to pursue education in STEM related fields, and she credits Fermilab for engaging in community outreach.

Outside her work at the lab, Esquivel co-founded Black in Physics, an organization that promotes the contributions of Black scholars to the field. Her virtual events in October garnered international attention with attendees from the U.K., Australia, Africa and Canada. She also works as an ambassador with If/Then, a group that seeks to empower young women in STEM-related fields.

Esquivel ended her presentation by encouraging others. “I want to say that you are not alone in this battle for justice, equity and inclusion. I’m here, and there’s people like me that are devoted to this work and that they’re pushing for transformational change across the country to make physics and STEM more inclusive.”

The life-to-particle-accelerator analogy works for Esquivel because it both mirrors her path and reaffirms what physics has taught her, that barriers are inevitable. But it also shows that like one of the tiniest particles works with, the neutrino, she can pass through anything.

Learn more about Dr. Esquivel’s work on her website or follow her Twitter.