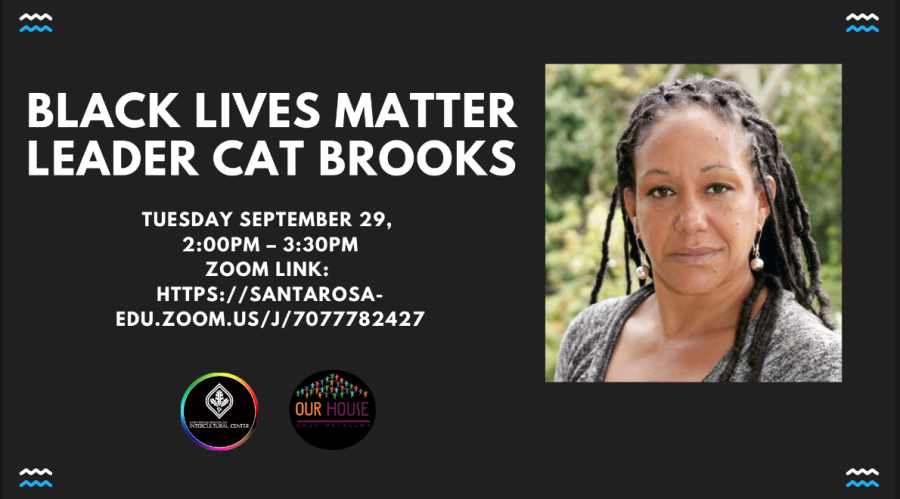

Cat Brooks, leader of Black Lives Matter and self-described “radical activist” with a national profile, spoke to more than 100 Santa Rosa Junior College students Nov. 2 about defunding the police and her history fighting racial injustice.

In her roles as Executive Director of the Justice Teams Network, co-Founder of the Anti Police Terror Project (APTP), and KPFA radio host, Brooks is focused on radical reform of policing, incarceration and mental health care — and even reforming the idea of protesting itself.

“We need to be visionary, not just reactionary,” Brooks said. “It’s still important to be reactionary and take to the streets to make people pay attention to injustices when they occur, but we need to also stop the violence before it happens.”

Brooks is no stranger to police-backed racial injustice. She witnessed it growing up in Las Vegas, in the 1980s but her call to activism came when she saw the video of BART Police Officer Johannes Mehserle killing Oscar Grant in 2009.

“That was my ‘enough’ moment. Something in me shifted that day,” Brooks said. “I was done. I cried, I got sick. I was holding my daughter, and knew I had to do something.”

Brooks said Oakland Police shot eight to 10 people a year when Grant was killed. In protest, Brooks formed the Onyx Organizing Committee; however, she realized the protests had little effect on the regularity of police shootings.

“We want to get to the gun before the bullet flies instead of standing with the mother as she’s putting her child in the ground,” Brooks said.

Brooks began to create models of what she wanted to see instead of waiting for the state to come up with a solution.

“We want to engage in reforms that are actually chipping away at the system so we can tear it down little by little until it’s completely demolished and we can build something else,” Brooks said.

One way Brooks affected change was through APTP’s “MH First” campaign. MH First is a non-911 response to mental health crises, substance use support and certain domestic violence situations. The program operates in Sacramento and Oakland.

Brooks said police are trained to use forced compliance, which is the expectation that a person will obey an officer simply because they are a person of authority. But this method doesn’t necessarily work on someone who cannot recognize the officer’s authority, like someone experiencing mental illness or an altered reality. Brooks pointed out that this method usually results in police officers using force on people already experiencing trauma.

“We are sending compassion and care instead of a badge and a gun.” Brooks said about community groups like MH First.

She also defined the concept of defunding the police, which is about redirecting resources and funds from militarized police and mass incarceration to community-led solutions for mental health crises, substance abuse issues and interpersonal violence

Brooks said our police officers have become our social workers, which isn’t what they want to do or are trained to do.

“Cops are not violence interrupters. They are violence responders. We need violence interrupters, and those people need to be born, bred, and resourced from the community,” Brooks said.

She pointed out the U.S. spends more money on incarceration than any other country, but doesn’t have less crime. Oakland is no different.

“We give the Oakland Police Department upwards of 50% of our general fund, and yet we remain on the top ten most violent cities list every single year. So what are we paying for?” Brooks said.

Oakland has a fiscal budget of $290 million for 2019-2020.

This is why Brooks believes systemic change is necessary; throwing more money at the problem isn’t solving it. She was involved in police reform legislation in both 2018 and 2019 , with California’s SB 1421 and AB 392.

AB 392 changed police officers’ use of force policy. Previously, police officers in California could use deadly force without scrutiny as long as they declared that their life was in danger in the police report. Now officers must use every possible alternative before resorting to deadly force.

SB1421 allowed police departments to release reports when an officer is involved in sexual assault or excessive use of force. Prior to SB1421, officers’ actions were shielded from public view by the Peace Officers Bill of Rights.

In addition, SB1421 prevents officers from hiding prior complaints when being hired in a new jurisdiction.

Brooks’ path toward activism started as a child.

While growing up in Las Vegas, Brooks witnessed her father’s suffering from mental health and substance abuse — which led to multiple encounters with the police.

“I grew up watching him get the crap beat out of him by cops on a regular basis,” Brooks said.

According to Cat, her father’s experiences with police were rooted in systemic racism. She learned the term “86’d” originated from the way LVPD officers would cover up their heavy-handed tactics with Black people — take them 8 miles out and bury them 6 feet deep.

Her own experiences with police officers also affected her drive for reform. When Brooks was 17-years-old, an officer pulled her and her boyfriend over and threatened her with rape But her final push toward activism came in 2009 when an Oakland police officer shot and killed Grant.

While Brooks favors structural reform, she had mixed feelings on Sonoma County’s Measure P, which will increase civilian oversight of the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office. She believes civilian oversight has limited effectiveness in America, but it’s a step in the right direction.

“People should vote for it and then be committed to fight like hell to make it work and then be prepared to put something else on the ballot in the coming years,” Brooks said.

Brooks’ energy beckons citizens to continue pushing forward for bigger broader change, not just a single ballot measure or piecemeal non-profit community groups.

“We are talking about revolution, we are talking about a different way of seeing our society. One that is rooted in love, compassion and care, as opposed to militarized police and mass incarceration.”