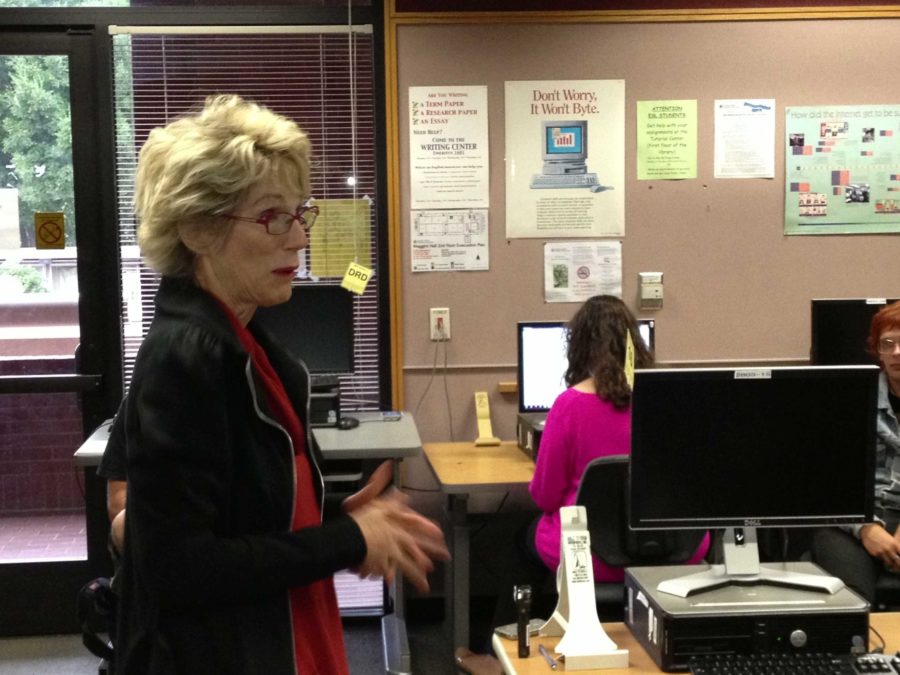

The daughter of the most famous confidential source in U.S. history did not know her father’s big secret until she was in her early 60s, she told SRJC journalism students on Oct. 24.

“He was willing to go to the grave with his secret,” said Joan Felt of her father W. Mark Felt, widely known as Deep Throat, the inside source who revealed the corruption and secrecy within the Nixon administration’s Watergate scandal.

For most of Joan Felt’s life, her father denied accusations he was Deep Throat from anyone who asked, even family members. “I believed my dad, that he was not Deep Throat,” said Felt, who teaches Spanish at SRJC and lives in Santa Rosa. “My dad wasn’t talking.” Though Felt had her suspicions, she kept quiet, and for many years American news media and history buffs debated exactly who Deep Throat was.

A confidential informant to reporter Bob Woodward of the Washington Post, Deep Throat was so named because he gave information strictly on deep background, meaning that he was never to be named as a source. With Deep Throat confirming information and giving the reporters leads, Woodward, along with reporter Carl Bernstein, exposed Nixon’s involvement in the infamous break-in at Watergate, the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters during the 1972 presidential election. Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974.

Joan Felt said she moved from town to town growing up as her father was transferred to various FBI field offices, eventually working his way up to managing field offices. She recounted one time when the family lived in Kansas City and a woman came to the house asking for her father. Once inside, she pulled off her wig and revealed that she was a he, and also a secret informant. “I was used to those kind of intrigues,” Felt said.

J. Edgar Hoover had apparently groomed Felt to take over the FBI, but Nixon snubbed him for the position and appointed Patrick Gray, with Felt as Gray’s second-in-command. “Gray was more of a figurehead,” she said. “He did not have a lot of experience but he was friends with Nixon. Gray was his pawn.”

After the Watergate scandal broke, the FBI began its investigation. Every day Mark Felt would take a file of what his agents had learned that day, stamp it as confidential, and leave it on Gray’s desk, who would then inevitably deliver it to President Nixon. Nixon’s response, according to Felt, was always: “This information is meaningless; do not continue with this investigation.” Though Nixon suspected Mark Felt after Woodward and Bernstein’s stories broke, he could not go after him because of the case’s increasing media attention.

For years after Watergate, reporters visited Felt’s house, asking him if he was “Deep Throat.” He usually said no and refused to talk to them.

However, there was one reporter who was remarkably different from the rest. “In the late 90s or early 2000s, a reporter came to our front door and asked to talk to my father,” she said. The reporter said his name was Bob Woodward. “I remembered his name from the newspaper,” she said, but didn’t connect him with Watergate. “I said, ‘don’t get your hopes up, but I will ask him’.”

When she told her father who was at the door, he invited him in, which Joan Felt recalls as “unusual for him.” She went out to run some errands, and upon her return, she noticed the two were still chatting away. “The two looked friendly with each other,” she said. Later, Woodward asked if he could take Mr. Felt to lunch, then said he needed to get something he had left in his car.

When Woodward left, Joan Felt remembered that she had to tell him not to let her father have more than one martini due to his medications. She looked out the window and saw Woodward walking the opposite direction from where he had come. Curious, she followed him in her car for several blocks and noticed that he got into a limousine eight blocks away. “I didn’t put the pieces together yet,” she said.

A couple months later, Joan Felt was with talking with her best friend about her father. She told her he had had a visit by a reporter named Bob Woodward. Her friend replied that she had read his articles and that he knew who Deep Throat was. “That was, for me, the moment of revelation,” Felt recalled.

Around the same time, her youngest son, Nick Jones, had a Stanford University roommate whose girlfriend’s parents invited the college students over for dinner parties. Jones often attended these dinner parties, which were hosted by an American history buff named John O’Connor. He was very interested in the Watergate scandal and had already surmised that Deep Throat must be Mark Felt. When the two were talking at one such gathering, Jones mentioned that reporters hounded his grandfather. O’Connor asked Jones who his grandfather was. Jones replied, “His name is Mark Felt,” and O’Connor said, “Nick, do you know that your grandfather possibly is Deep Throat?”

Nick told his grandfather all of this, including when O’Connor asked to meet him in person. Felt initially refused, insisting that he did not care to be interviewed by anyone. But O’Connor slowly gained his trust and the two shared many private conversations.

Joan Felt became more suspicious than ever that her father was covering up the truth. She decided to pressure him into coming out to the public. Her tactics were subtle and took more than two years.

“I used every ploy I could think of, including showing him [the film] ‘All the President’s Men,’” she said. “But he kept dropping hints unintentionally. I would say: ‘Dad, do you realize that Deep Throat singlehandedly brought Nixon down?’ And he would reply, ‘I wasn’t trying to bring him down!’”

Felt said her father didn’t want people to think he was disloyal to the FBI or to his country. He went to reporters because his bosses, Grey and Nixon, were not to be trusted. Felt worried he would be judged a traitor, not a hero.

In 2005, Mark Felt finally felt that the social and political climates were right for him to come out, and so he did. O’Conner had set up a tell-all interview with Vanity Fair magazine. He did not remember everything clearly, as he was in his 90s and suffering from the onset of dementia, but he remembered enough to explain his side of the story. But given his dementia, both Joan Felt and her brother worried that maybe they had badgered their father into believing he was Deep Throat. They were relieved when Woodward confirmed it.

“The day that story came out,” Joan Felt said, “our whole neighborhood was filled with reporters and TV cameras. You couldn’t even get to the house, so many vehicles with satellites on top. We were suddenly in the spotlight.”

In May of that year, Woodward released his book “The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate’s Deep Throat,” a compilation of Woodward’s encounters with Felt over more than 15 years.

After the initial rush of publicity, the story calmed down, as did the news media and reporters. Deep Throat, the last loose end of the Watergate drama, was public. Mark Felt died at the age of 95 in 2008.

“At the end of his life, he was happy. He relaxed considerably, glad to have his secret revealed,” Joan Felt said. “He was famous for those last few years. The rest, really, is history.”

Unveiling Deep Throat’s secrets

About the Contributor

Brenna Thompson, Copy Editor, Spring 2014