The irony was not lost on Santa Rosa Junior College student-employee Alonso Rodríguez Villalobos that he had to quit his job as a student success coach — a job he loved — because the pay was too low.

His job duties included providing individual students with support — tips on time management and study skills — as well as giving speeches and leading workshops on topics like self-care and finishing the semester strong. And he connected students to resources, like financial aid, free food kiosks and counseling. He learned new skills like public speaking, teaching and coaching in the process of supporting other students.

“I really didn’t want to quit my job,” Rodríguez-Villalobos said. He could barely afford the gas to get to work and school, and he could earn much more working for an off-campus employer.

So Rodríguez-Villalobos did what a half-dozen student-employees in his department, and several dozens more campus-wide, would do over time: he quit.

Working as a student-employee in spring 2023, Rodríguez-Villalobos earned $15 to $16 an hour.

SRJC student-employees earn an hourly wage according to a schedule set by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which contracts with the college. As of Aug. 10, 2023, according to SRJC Human Resources, student-employees initially earn $16.50 an hour.

After completing 200 hours of work, they are eligible for an evaluation and potential pay raise to $17 an hour. After 600 hours of work, combined with a positive performance evaluation by a supervisor and the completion of a work experience class, they may be eligible to earn $17.50 an hour.

The pay scale differs for international students, who earn $15 an hour and are capped at 20 hours a week while school is in session, and a maximum of 25 hours a week during official school breaks, according to the SRJC website.

Now Rodríguez-Villalobos works at Humanidad Therapy and Education and earns about $25 per hour.

He, like many other SRJC students, found that working off-campus pays better. Students who work at fast-food restaurants like McDonald’s or Jack-in-the-Box can earn $20 or more an hour, thanks to a California law that came into effect April 1. The new law mandates that fast-food restaurants with 60 or more locations nationwide must pay their workers at least $20 an hour. Students report they can also earn $20 an hour or more at a local retail store such as REI or more than $20 per hour for a Santa Rosa City internship.

These jobs, however, may not provide students with experience and skills that will lead to higher-paying jobs in their field of choice. But with endless post-pandemic inflation increasing the cost of living, such choices are luxuries some students don’t have.

The minimum wage set by the Sonoma County Junior College District is lower than minimum wage in the cities surrounding the two campuses. Both Petaluma and Santa Rosa set the current minimum wage to $17.45, which will adjust annually to align with the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners (CPI-W).

In contrast to SRJC, the Peralta Community College District sets student wages to match the surrounding cities in the East Bay. At College of Marin, student-employees earn $17 or $18 an hour depending on their level, which is somewhat aligned with the county living wage ordinance. The College of Marin raised student wages in August 2023, said Kessa Kaplan, a human resources technician at the college. At Napa Valley College, student-employees earn $16 an hour, equivalent to the minimum wage in Napa.

We Became Student Advocates

Rodríguez-Villalobos, along with other student-employees, first brought up the problem of low wages with a trusted advisor and SRJC humanities and religious studies professor, Rafael Vazquez Guzman. He told them about other students who had successfully pushed the administration for a wage increase in 2019, bringing student wages from $12 an hour to $15.

Since the 2019 pay raise, however, the cost of living has risen far more rapidly than student wages. The pandemic played a role in this, as the economic slow-down created ripple effects throughout the economy. Since 2020, prices have risen about 20% nationwide and slightly more so in California.

If student wages had kept pace, student-employees would earn at minimum $19.80 an hour. Prices for food, clothing, gas and other services continue to rise, causing financial insecurity for many SRJC students. Stagnant student wages compound this problem.

Vazquez-Guzman encouraged Rodríguez-Villalobos and Kelly Zamudio, president of student organization M.E.Ch.A., to push the administration for a living-wage raise.

“If you were getting paid $15, it [becomes] very difficult to do that job of helping students or just the campus overall, because you couldn’t afford to have basic needs,” Zamudio said, speaking for students who shared their work experiences with her in 2023.

Zamudio worked at Our House Intercultural Center on the Petaluma Campus. Like Rodríguez-Villalobos, Zamudio loved her job but couldn’t make ends meet. She, too, quit.

“I feel like my job was very rewarding for myself and for other students, because you’re able to create so much content or workshops that kind of follow the guidelines that SGC teaches about diversity, inclusion and racism, no passivity, stuff like that,” she said. “We saw that a lot of the students were leaving, because they got other jobs either at fast food or in other places.”

In April 2023, Zamudio and Rodríguez-Villalobos drafted a petition they submitted to then SRJC President Dr. Frank Chong and members of the Board of Trustees. The petition focuses on the student-wage inequity, arguing that students should not earn less than the minimum wage in Santa Rosa and Petaluma. Because SRJC is a district, it is not required to follow the cities’ minimum wage. The student activists demand that student workers receive a living wage, pointing out that Target paid new employees a starting wage of $18.50 in 2023. As of April 2024, 564 people signed the petition in support of it. To date, neither the new president, Dr. Angélica Garcia, nor the board members have signed or responded directly to the petition.

Nobody Talks About That Here

The college employs approximately 290 students, or 11.7% of the student body, in jobs that range from front-desk staff in counseling, Bertolini Information Extended Opportunity Programs and Services (EOPS) and Tech Desk at the library, to student researchers, teaching assistants and student-success coaches.

A little under half of these students earn $16.50 per hour and about half earn $17 an hour. A small percentage earn $17.50 — 14 out of 290 — according to data provided by Sarah Laggos, SRJC interim director of communications.

Many students report that they value their college jobs. They describe skills they gain, such as leading meetings, giving presentations, advising and mentoring, or working with clinicians, counselors or instructors in fields they are interested in. Beyond the pay, students learn how to function and succeed in professional environments, skills that are difficult to quantify and impossible to fake without experience.

Many students didn’t realize that they earned less than minimum wage.

Even Logan Warren, student representative to the Board of Trustees and a student-employee himself, did not know. “I first learned about this in June 2023,” he said.

Neither had Khansa Tariq, student-employee who works the front desk in the counseling department, nor Malala Amdriantsoa, who works at the Tech Gear desk in Doyle Library. Nor did a student-employee in the EOPS office.

Both Tariq and Amdriantsoa expressed surprise when they learned, as did supervisors who overheard the conversation between the student-employee and an Oak Leaf reporter in the library and in the EOPS office.

“Nobody talks about that here,” Amdriantsoa said in an attempt to make sense of the wage discrepancy. An international student, she has worked at the college for a year and accumulated 600 hours, but lacks the time to take the required work experience class to earn the higher Step 3 wage, she said.

Tariq sought her position deliberately to gain contact and experience with counselors. To her, the job represents academic access. But she acknowledges her privilege: living at home, she does not need to use her salary to pay for living expenses.

Still, her earnings do not go far. At first, her dad disapproved of her on-campus job. Limited to four hours a week, her earnings barely covered the gas she needed to get to campus from Rohnert Park. But now that she takes on-campus classes, she works more hours, which helps justify the gas expense.

Amdriantsoa, an international student, has no choice but to work on campus. International students’ visas require on-campus employment. She believes wages should rise each year to match rising living expenses.

To This Day I Can’t Make an Omelet

President Garcia said she fully supports students earning a living, dignified wage. She has worked since high-school, first in restaurants owned by family members and later for a mail and package company. She also worked as an undergraduate to pay for her tuition and living expenses.

Garcia knows first-hand the challenges student-employees face. As an undergraduate, Garcia worked in the college cafeteria for 25 hours or more a week. She supplemented these hours by babysitting for about 10 hours a week. At the time, budgeting her expenses was “pretty stressful,” she said.

Her situation changed when she rose to the level of student manager in the dining hall and resident adviser. While her employment covered her room and board, the work was hard, Garcia remembers. She worked weekend brunch, which was “kind of rough, on a college campus,” she said. Since then, she can’t bring herself to make another omelet. Despite the challenges, though, her work experience provided more than just the money needed to cover her books and basic expenses.

She learned a lot about developing a work ethic and working with people from diverse communities, she said. As a student manager to student-employees working in the dining hall, she emphasized that they contributed “good, honest work.” Early in her leadership career, Garcia pointedly acknowledged the fundamental relevance of human dignity in employment.

Fighting for This Since the Beginning

Garcia notes that today’s students face similar and probably greater challenges. Many SRJC students work not just to pay for books and tuition, but also to support their families.

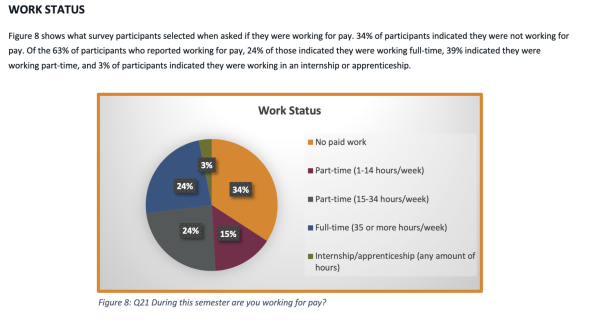

A student engagement survey conducted in 2022 reports that 66% of SRJC students work, either on or off campus. According to the report, of SRJC students who work, 24% work 15-35 hours per week and 24% work 35 or more hours a week, “essentially full time jobs,” Garcia said.

On April 11, 2023, the Board of Trustees unanimously selected Garcia as SRJC president, noting her contributions to educational equity. At the public forum that day, Garcia expressed her gratitude for “a chance to do what I love, which is to help to disrupt the institutionalized racism, classism, sexism [and] all the things that keep people from being able to thrive.”

At the same time, she acknowledged that her work depends on the participation of the entire SRJC community. “Collectively, we are going to change the opportunity to disrupt generational poverty in this state,” she said.

Collective action requires the participation of all stakeholders. Especially those most impacted, such as student-employees. Like the board members, Garcia supports student-activists who bring their concerns to the monthly Board of Trustees meetings. “I appreciate students’ using the appropriate space for voice and agency,” Garcia said.

Students who have spoken at board meetings, however, lament that they’re not heard. “When we do talk at the meetings, there’s tension and mixed feelings with their body language,” Zamudio said.

She described trustees typing, looking away and, on one occasion, applying lipstick when a student began speaking.

“We don’t feel like they receive our message; we often feel ignored,” said Rodríguez-Villalobos, one of the students who spoke at Board of Trustees meetings. This discouraged the students but, at the same time, “that discouragement lit a flame on us to keep trying on us to teach and not give up,” Zamudio said.

Speaking for the “incredibly student-centered” Board of Trustees, their perspective is “give us the information so that we can take action,” Garcia said. She describes the board, who know first-hand the cost of living in Sonoma County, as very supportive and attuned to the students’ needs.

Student Trustee Warren has been listening. While acknowledging that it’s “tricky” to negotiate with the union for higher student wages, he supports the students’ activism. “I’ve been fighting for this since the beginning. I’ve spoken about it every board meeting and, while I’m glad the administration has taken steps, I am hoping that changes will happen soon,” said Warren, though the boards’ student representative doesn’t get an official vote. For SRJC, one of California’s best community colleges, paying student-employees less than minimum wage “sounds terrible. It is terrible,” Warren said.

Warren holds office hours and has even set up a table outside to make himself visible to students. “I want more people reaching out to me,” he said.

Ezrah Chaaban, president of the Board of Trustees, emphasized the importance of student-employees to the SRJC community. “SRJC’s Board of Trustees is committed to supporting student employees with fair wages for their work. We appreciate student input and want students to know that their voices are heard and we are working to address these concerns,” he said by email.

Individually, some board members concurred. “Personally, I support a fair wage for students and have indicated that to our team,” trustee Maggie Fishman said by email.

But other stakeholders exist in addition to student-employees, President Garcia and the Board of Trustees. As a public institution, SRJC has collective bargaining agreements with union organizations, specifically, SEIU. The Oak Leaf reached out multiple times over four weeks to two SEIU spokespersons associated with SRJC. Both declined to comment on student-employee wages.

Negotiations with SEIU need to progress in a certain order, Garcia explained. That said, the administration, the Board of Trustees and SEIU are actively in the process of working out student-employee wages as well as bilingual student-employee pay rates.

“I want to be very clear that we’ve been looking at both the increase of the minimum wage matching Petaluma and Santa Rosa, [as well as] the recent state law [that raised fast-food employees’ wages] to $20 an hour,” Garcia said.

Garcia recognizes and understands students’ frustration over the slow pace. But students continue to wonder why it is taking so long.

“The honest answer is because there are multiple moving parts, some of which I have no control over. And in our relationship and partnership, we’re doing our piece,” Garcia said.

Student Trustee Warren praised Garcia’s efforts to adjust student wages and emphasized that it is a top priority for her. He has been working with Garcia on the issue and explained that union regulations contribute to the hold-up.

He quoted from the SEIU regulations that state short-term, non-continuing (STNC) employees cannot earn less than student employees (Article 5, Section 5.13).

In other words, the lowest-paid STNC employee must make more than the highest-paid student-employee.

In order to raise student wages, SEIU will need to be on board to raise STNC wages as well, he said. As of June 2023, the lowest rate for STNC is $17.75, or 25¢ more per hour than the highest paid student-employee.

Will Students Have to Fight for a Living Wage Every Year?

Rodríguez-Villalobos and Zamudio, leaders of the student movement for higher wages, presented their petition a year ago in April 2023. Warren, the Student Board of Trustees representative, has been working on this issue since June 2023.

Months have passed and the delays compound the problem, Rodríguez-Villalobos and Zamudio said.

They fear the delays will result in the movement losing momentum.

“What will happen once we transfer to a four-year college?” Zamudio wondered. Zamudio and Rodríguez-Villalobos will finish at SRJC in spring 2024 and transfer in the fall. Will students have to fight for a living wage every year?

They want the administration to explain what’s taking so long.

“I know, I know. I know. And I know, I hear you,” President Angélica Garcia said in response.

Garcia does not know whether student-employee wages will rise before the end of this academic year. She hopes so, but she won’t overpromise and underdeliver.

“I know that we [the administration, Board of Trustees and SEIU] care deeply about the college and the community. And I see a strong sense of support and collaboration,” she said.