Temperatures rise, waters rise and now tensions rise, as climate change becomes an increasingly prominent topic in legislation and politics across the world — with 53% of Americans having experienced extreme weather in recent years, according to a CBS News poll.

From fire to floods, Sonoma County is no stranger to the devastations of natural disasters amid a changing climate. As student concern for sustainability surges and the issue’s presence becomes ever-pressing, Santa Rosa Junior College proceeds in an ambitious pursuit of achieving zero energy, zero water, zero waste and carbon neutrality by 2030.

“We have come a long way,” said SRJC Waste Diversion Technician Guy Tillotson regarding SRJC’s sustainability progress and plans over the course of his seven years on campus. “But we have lots of goals.”

SRJC’s Sustainability Committee, composed of students, faculty, classified staff and administrators, outlines how to allocate resources — notably $35 million from the Measure H Bond — and plan for an environmentally-friendly college in “Sustainable SRJC Greenprint,” a document President Dr. Frank Chong initially signed in 2015.

New drafts of “Greenprint 2.0” are now in the works, outlining initiatives within eight distinct categories, including transportation, curriculum and education, engagement and culture, resource use and climate, built environment, economics, food, and administration and organization.

“This district tries to put its attention on students and student support more than anything else,” Tillotson said. “So the committee and I are always like, ‘Don’t forget about sustainability; keep working on it a little bit.’”

Throughout the past decade, SRJC pursued several of these developments in the college’s infrastructure and practices — many of which are materializing in physical structures and administrative decisions today.

Zero Net Energy

Achieving zero net energy will require SRJC’s energy consumption to be equivalent to or below its renewable energy production.

“There’s holistic planning around how much energy we’re using and where it’s going,” SRJC Energy and Sustainability Manager David Liebman said.

SRJC’s largest source of renewable energy is photovoltaic arrays and solar panels, placed on buildings and carports. Estimated to save more than $1 million a year, the systems complement each other to provide an estimated 60% of energy needed to run the Santa Rosa campus, 100% at the Petaluma campus, 100% at the Public Safety Training Center and 90% at Shone Farm. They’re also expected to be implemented at the Southwest Center during its ongoing construction process.

“The big change is beginning to see that we are making a sustainable energy infrastructure system,” Liebman said. “How do we start generating our energy as close to us as possible, how do we store that energy and how do we efficiently use what we’re storing?”

At SRJC, a significant portion of that solar energy is stored in a micro-grid on the Santa Rosa campus. Photovoltaic arrays convert solar energy into electricity that gets stored in batteries, a process that is amplified during peak hours of use. The stored electricity supplements regular energy needs and can be used during power outages.

“These projects work together to create that real sustainable energy infrastructure that we need to reach our goals,” Liebman said.

SRJC’s sustainability managers also oversaw the development of the Geothermal Plant Project, composed of 300 geothermal bores that are 400-feet-long and buried beneath Bailey Field. The groundwater, which has a constant temperature that is warmer than the air in the winter and cooler than the air in the summer, is transferred through small pipes to heat or cool Burbank Auditorium, Garcia Hall, and Analy and Forsyth halls.

“Maintaining the heating and cooling systems of 100-year-old buildings is very difficult,” Tillotson said. “We’ve replaced a lot of the [old] systems.”

Additional energy reduction plans include the installation of LED lights on the Santa Rosa and Petaluma campuses, which will save an estimated $300,000 a year and improve lighting quality.

“We’re producing renewable energy at each site,” Liebman said. “We’ve done significant energy efficiency improvements, and each site has a lot more underway.”

SRJC’s new dormitory at the soon-to-open Polly O’ Meara Doyle hall, is tied to the same energy system as the rest of the campus and will be able to optimize current solar power and heat pumps; Liebman also plans to add solar panels that will offset some of the impact.“One of the challenges with this building was how to maximize keeping rents low while achieving high sustainability,” Liebman said. “It’s just one of those design entities that we’ll have to keep working through.”

Eliminating net nonpotable water consumption

The Greenprint 2.0 calls for using potable water in volumes equal to or less than the amount of rainwater that falls on campus within a year, and non-potable water being used for all irrigation, plumbing and all other non-drinking purposes possible.

One of the larger contributors to this goal is SRJC’s Quinn Central Plant Project, expected to reduce the Santa Rosa campus’ water usage by roughly 20%. Its tank, located near Maggini Hall, holds 50,000 gallons of water, most of which will be used for irrigation, plumbing and cooling towers.

The plant collects water from a natural spring that was discovered in the 1970s, during the initial digging process for the Quinn Swim Center. It’s been long treated as a hazard for basement flooding; for years, SRJC transferred the spring water to the storm drain in a hasty attempt to alleviate the risk.

“It ended up being close to six or seven million gallons of water a year,” Liebman said. “To put that into perspective, the Santa Rosa campus uses about 25 million gallons of water a year — so 25% of all of our water supply, we were just pumping into the storm drain.”

The plant runs on an entirely separate plumbing system to prevent cross-contamination with clean drinking water, subsequently limiting its ability to be implemented in newer buildings. “To do more buildings over time, we’ll really phase into them as those buildings go through renovations,” Liebman said.

It’s gone through several trials with completion projected for June 2023.

Auditorium, Garcia Hall, Analy Hall and Forsyth Hall, starting June 2023. (Max Mwaniki)

SRJC’s Petaluma campus also uses reclaimed wastewater for irrigation, optimizing its close proximity to a wastewater plant.

“Recycled water is held to a high standard. It would be better to use that water than fresh drinking water, which is really vital and important for people; it isn’t needed to water our lawns or water our plants,” Liebman said.

“One of the challenges with this building was how to maximize keeping rents low while achieving high sustainability,” Liebman said. “It’s just one of those design entities that we’ll have to keep working through.”

SRJC currently diverts 50% of its waste; Tillotson drafted a goal of 80% by 2030 in Greenprint 2.0. “To me, zero waste means doing everything you possibly can, to reduce the amount of waste you produce and then how much you divert,” he said. “So the procedure would be to identify the kinds of waste you’re producing and come up with strategies to reduce it.”

Reducing and diverting campus waste

Tillotson noted a significant decrease in campus landfill waste during his time at SRJC, after the Sustainability Committee advocated for a designated person to focus full-time on waste management and raise awareness about excessive waste on campus.

“I set up a bunch of systems to increase the number of bins and to talk to people,” he said. “The garbage started going down, and the recycling started going up; it was great.”

Tillotson is currently working to pass a single-use plastics resolution, wherein departments would no longer be able use single-use plastics for items such as utensils, bags and food containers.

“You can’t walk into every classroom and talk to every student,” Tillotson said. “Passing laws and passing resolutions to eliminate waste is a lot better than just going around saying, ‘Hey, thanks for using a travel mug.’”

He’s also responsible for so-called “waste installations” seen throughout campus, which highlight common sources of waste from students– primarily coffee cups and plastic water bottles, casually arranged across a lawn. “The district culture allows for that kind of expression,” Tillotson said.

The installations began to appear around 2017 and gradually grew to occupy more space. “People say [the installations] have an effect on them; that’s why I keep doing them,” Tillotson said. “You have to push boundaries a little bit to create discomfort.”

compost, a number that has considerably grown over time. (Dharma Niles)

Tillotson also observed a sharp decline in paper waste since COVID-19, as a change to online learning led several departments to reduce paper use indefinitely. “Everyone was relieved,” Tillotson said. “Several people, including myself, were like, ‘It’s time to just leave it online.’”

Tillotson expects SRJC’s new student housing to lead to a significant increase in campus waste initially — however, he also sees the change as an opportunity to promote healthy and sustainable choices in tandem with SRJC’s food vendors. This would prospectively include more plant-based and locally sourced options within students’ meal plans and at campus vending machines.

“A lot of people don’t have cooking experience; they’re going to tend to bring a lot of fast food back to their room and throw it all in the garbage,” Tillotson said of student incoming dormitory residents. “But if we have alternatives available, and some education about a zero-waste lifestyle, then they’re gonna be influenced to live a more sustainable lifestyle.”

Carbon neutrality means improving transportation options for students

Besides structural changes, carbon neutrality also addresses individual habits that contribute to methane, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions. It involves optimal reduction of carbon output, in tandem with carbon-offsetting behaviors.

“Carbon neutral operation really focuses on the things that are within the college’s control,” Liebman said. “It’s reducing our emissions to a point where our energy electricity is clean, we’re shifting away from gasoline and diesel for vehicles and generators, and using electricity — as well as natural gas — for heating our buildings or cooking.”

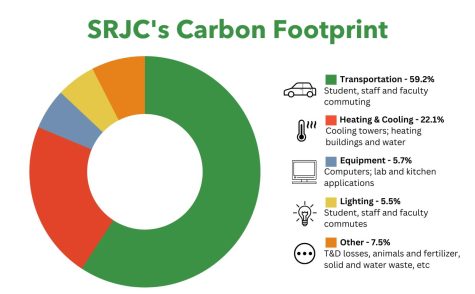

Students and staff driving themselves to campus is the largest contributor to SRJC’s greenhouse gas emissions, estimated to comprise 60% of the school’s carbon use.

“We don’t want to say, ‘Everyone needs to take public transportation’; public transportation doesn’t work like that,” Liebman said. “But we acknowledge that driving a single-use vehicle that’s powered by gas is our largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and to a changing climate.”

But SRJC’s “commuter school” nature makes this a challenging number to tighten. Coordinating bus schedules and other sustainable transport options becomes unrealistic with more than 20,000 students attending classes on SRJC’s five campuses.

footprint. While its “commmuter school” status makes this a challenging number to fix,

SRJC’s sustainability team is working with the City of Santa Rosa on solutions. (Dharma Niles)

SRJC’s sustainability team is currently corresponding with the City of Santa Rosa to implement sustainable transportation that’s more feasible for students, including new public transport from Sonoma to SRJC and a bus schedule that runs more frequently and at later hours.

“[Public transportation] is going to be much more convenient for students and staff the more frequent the transportation is and the more flexible the schedule is,” Tillotson said. “So we’re advocating for those things.”

SRJC students are eligible to receive free Clipper Cards through the Clipper BayPass program, currently set to run through summer 2024. The cards waive students’ transportation costs at any Bay area public transit system that receives Clipper, including the Santa Rosa CityBus, SmartTrain, San Francisco Bay Ferry and BART.

“The BayPass is one program I can really attest to,” said student Jason Loureiro at SRJC’s Climate Action Night April 20. “I use it to commute to my job after the JC, and it’s really saved me a lot of money on gasoline.”

Several sustainability committee members have also called for attention toward the “bikeability” of SRJC’s Santa Rosa campus and surrounding area.

“If you’re on a bicycle, you’re on your own,” said Alexa Forrester, SRJC philosophy instructor and Bikeable Santa Rosa volunteer. “So what you get is bicyclists doing everything like riding against traffic or cutting across lanes; it’s not safe for anybody.”

Bikeable Santa Rosa, a nonprofit organization advocating for safer biking opportunities throughout the city, has additionally directed attention toward improving the roads surrounding SRJC and campaigning for “protected and connected bike lanes into and around campus,” Forrester said.

Most roads immediately surrounding SRJC have no designated biking area, and those that do are highly trafficked and offer minimal space. “It’s just intense fumes and checking over your shoulder,” Tillotson added, referencing the bike lane on Mendocino Avenue.

Forrester also commented on new construction at SRJC’s Southwest Center; she believes the campus’ infrastructure limits opportunities for sustainable transportation.

“If we really want to help our students choose alternatives to cars, making our campus welcoming to bikes and making people on bikes feel like they’re welcome here, that’s going to help change the culture,” Forrester said. “And it would really help our greenhouse goals as a community if we could have more people biking to campus.”

The City of Santa Rosa also recently postponed construction for the bicyclist and pedestrian bridge extending from Elliott to Edwards Avenue after reallocating funding. The original proposed bridge, which offered students on the Santa Rosa campus easy access to Coddingtown Mall rather than having to cross Highway 101, went through additional stages of design refinement in December 2022 before getting delayed.

“There is still some money for the bridge, but the city needs to back it,” Sustainability Committee Co-chair Abigail Zoger said. “What I would like to see is SRJC students, SRJC student government, SRJC faculty and SRJC administrators be more active with the City of Santa Rosa in the County of Sonoma, demanding sustainable development that helps our students.”

Because eliminating transportation-related emissions isn’t possible for a large portion of students, given uncoordinated work schedules and other personal circumstances, SRJC is taking other measures to minimize its impact and offset the impact of greenhouse gasses.

“That’s the reality of the world,” Liebman said. “Student responses tell me, ‘Okay, I need to make sure to invest in electric vehicle infrastructure,’ because there are students who might eventually get an electric vehicle.”

The new dormitory is also expected to help reduce SRJC’s transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions, potentially bleeding into its overall carbon footprint. “Having on-campus residence halls is an excellent idea for sustainability,” Tillotson said of the new construction. “So I’m hoping we build a second, even a third, residential tower.”

Shone Farm’s acreage also provides SRJC “carbon credit” that shrinks the district’s total carbon footprint. Crop photosynthesis sequesters carbon in the soil, which is subsequently subtracted from final emissions calculations.

Individual impacts

SRJC Energy and Sustainability Manager David Liebman urged students to reach out to college leaders and administrators with suggestions that the college should take regarding climate-related resolutions.

“As we get to every younger generation, their future is becoming more and more impacted by the changing climate,” he said. “Students have a voice; it’s all based around power and what students want to see.”

Sustainability Committee Co-chair Abigail Zoger also emphasized the importance of student advocacy for larger scales of change.

“I think individuals can do lots, but I’d like to see students get involved with city and county politics,” Zoger said. “The truth is that we have to make systemic change.”

Tillotson also noted that sustainable choices can be more economical for students; they often involve minimizing consumerism and purchasing fewer high-waste products.

“Sometimes it’s just habits, not buying a huge pack of water bottles and refilling at home,” Tillotson said. “Who wouldn’t want to save four, five, six hundred dollars for just a little habit?”

The big picture

Liebman added that students have opportunities to get involved in sustainability-related clubs as additional ways to support campus initiatives.

“Whether it’s about biodiversity, landscapes or learning about renewable energy and wanting to see it on your campus, students getting together with a passion for sustainability provides so much power in expanding the culture of sustainability,” he said.

To quantify and compare its environmental performance, SRJC became the first California community college to implement the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS), by submitting to the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education extensive data detailing the college’s emissions, waste and energy usage.

SRJC’s bronze ranking expired in 2022, but a reevaluation is expected within the next year and a half.

“We’re hoping that by then we’ll achieve a silver ranking,” Liebman said. “We might be able to push it to a gold.”

As SRJC proceeds to expand resources for students, climate advocates push for the administration to implement sustainability-related infrastructure and practices that support the 2030 goals set by Greenprint 2.0.

“By this time next year, we’ll probably be around halfway there,” Liebman said of the college’s 2030 goals. “But even with all the amazing work that we’re doing, being halfway there still means we have a long way to go.”