Note: Maia Kobabe’s pronouns are e/em/eir.

Maia Kobabe, author-illustrator of “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” sits atop a picnic table at Ragle Ranch Regional Park, eir legs perched on the bench. Kobabe (pronounced koh-BABE) pauses to point out birds during our conversation and to appreciate the laughter of kids at the nearby playground.

E has one long earring that catches the dappled sunlight while we talk. Kobabe’s outfit — yellow pants, a black sweatshirt with the brand name FILA colorfully embroidered across the chest, the long earring — is familiar to me because e illustrated the look in a recent Instagram post showing off what Kobabe and eir friends wore to K-pop concerts last year.

K-pop and Sonoma County’s natural beauty are two things bringing Kobabe joy at a time that’s also caused em fear and fatigue. According to the American Library Association (ALA), “Gender Queer” is the most-banned book in America.

When it came out in 2019, “Gender Queer” was hailed as a powerful story, great resource and queer-comics classic. The first run of 5,000 copies sold out within a week.

Kobabe’s first book, “Gender Queer” is an illustrated coming-of-age autobiography about eir journey of self-discovery as a nonbinary and asexual person. The story chronicles Kobabe’s upbringing in rural Sonoma County and eir social experiences in grade school through grad school. E attended San Francisco’s California College of the Arts, where eir professor Melanie Gillman was the first openly nonbinary person e met.

Kobabe, now 34, depicts decades of dissonance between eir self-conception and society’s gendered expectations of em. During Kobabe’s childhood, eir parents never enforced gender roles on themselves or their children. E frequently felt like kids at school had access to information e lacked about things like shaving and using deodorant. Kobabe also struggled academically until e learned to read at age 11. This launched a lifelong love of books; from then on, e devoured fantasy books and later, queer stories.

“Gender Queer” palpably conveys Kobabe’s experience of gender dysphoria. Yet, what’s more striking is how well it also conveys instances of gender euphoria — profoundly positive experiences when Kobabe feels harmony between eir nonbinary identity and gender expression. Kobabe feels euphoria when e begins to use the pronouns e/em/eir and when e buys clothes that feel “queer and magical.”

Alongside eir exploration of gender, the book also documents Kobabe’s path of sexual discovery, from teenage crushes to masturbation to first times with a partner. Kobabe determines that e has a lower libido than most people e knows and that what arouses em in fantasy isn’t always enjoyable to do with a partner. Ultimately, Kobabe comes to identify as asexual.

“‘Gender Queer’ is the only time I’ve ever seen anything even remotely close to my identities,” says Alex Brown, a high school librarian, author and award-winning book critic who is genderqueer, asexual and aromantic.

“I came to [the book] long after I’d already come out, so it had no effect on my journey of queer discovery. But unless you’ve never seen yourself represented in media before, you don’t know how impactful representation can be. Maia and I dealt with so many of the same questions and concerns about relationships — both with others and with our own bodies — that I wish I’d had this book as a teen,” Brown says.

Stuart Wilkinson, a gay man who works as a teen-services librarian in Guerneville, calls “Gender Queer” a lifesaving work of art for LGBTQIA+ teenagers and adults.

“When you’re able to see yourself in a nonfiction book like this, especially a beautiful book to look at, I really do think this has a profound impact on mental health,” he says.

In 2020, “Gender Queer” won two major awards from the ALA — a Stonewall Honor in Non-fiction and an Alex Award, which recognizes “books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults ages 12 through 18.”

Then the challenges began.

As libraries and bookstores all over the country bought and displayed Kobabe’s celebrated work, conservative groups took notice, launching efforts to ban “Gender Queer” among a slate of other titles, mostly about LGBTQIA+ characters and characters of color.

Beginning in 2021, the ALA documented a massive surge in calls to ban or censor books in schools and public libraries. For nearly two decades, it tracked censorship efforts on fewer than 300 book titles each year; in 2021, more than 1,800 titles were under attack and by 2022 the number rose to more than 2,500.

Kobabe’s illustrated memoir was at the epicenter.

Kobabe says “Gender Queer” was especially susceptible to book challenges for several reasons — it was readily available in most libraries because of the awards it won, its title comes up immediately when one searches the words ‘gender’ or ‘queer’ and it’s a comic.

“Many of the biggest award-winning names in comics — ‘Perspeolis,’ ‘Maus,’ ‘Fun Home’ — are solidly books for adults, but there are people who see anything with pictures and think it’s a children’s book,” Kobabe says.

E also says books with pictures are vulnerable to misinterpretations that easily go viral on social media. Calls to censor comics are common enough that there is even a nonprofit organization, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, dedicated to protecting the First Amendment rights of the comics art form and its community. The organization issued a statement of support for “Gender Queer” when the challenges began.

“This nuanced memoir examines nonbinary gender identity in a way that benefits both those who identify as nonbinary and those who wish to better understand nonbinary identity,” the organization said. “In the case of ‘Gender Queer,’ challengers have taken a scant handful of out-of-context images to falsely assert that the graphic novel is pornographic and obscene.”

Ironically, having a banned book has come with some silver linings.

“Not every book that’s challenged sees sales increase, but mine did,” e says.

Articles about Kobabe appear in Time Magazine, The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times, among other prominent publications. E has written opinion pieces for NPR and The Washington Post. E also has more speaking opportunities than ever before. In April, Kobabe traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak to librarians at the Library of Congress and to members of the Gay, Lesbian, and Allies Senate Staff Caucus.

“It’s given me a platform and a voice I didn’t have before. I’m trying to use that to the best of my ability,” Kobabe says.

Despite the personal successes the attention has brought, Kobabe wouldn’t choose to be in eir position.

Why are books under attack?

“I’m seeing all of these communities just completely tearing themselves apart over queer books and queer voices and, basically, whether or not they believe that queer and trans people are appropriate in the public sphere,” e says. “All of the personal benefits are pretty much outweighed by my fears over the rise of censorship, the defunding of libraries and all of the anti-trans legislation that’s being passed — limiting health care, bathroom access, sports team access and the teaching of history and pedagogy.”

E continues, “The wave of book challenges that started in 2021 was fueled by a very organized and intentional conservative push to make trans rights the new hot-topic talking point along with things like abortion and immigration,” Kobabe says.

E isn’t alone in characterizing book bans as part of a broader push against trans visibility and rights in the U.S.

In 2022, Randall Balmer, a Dartmouth professor of religion who researches evangelism in America, told The 19th* that the rise in anti-trans legislation is an effort to keep the religious right voting Republican.

“They have an interest in keeping the base riled up about one thing or another, and when one issue fades, as with same-sex relationships and same-sex marriage, they’ve got to find something else. It’s almost frantic,” Balmer said.

After same-gender marriage in the U.S. became legal in 2015, opposition to marriage equality quickly dwindled. Trans rights became the next issue to galvanize white evangelical voters, Balmer said.

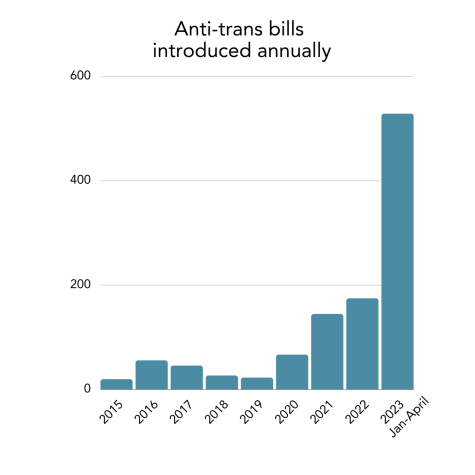

The website “Trans Legislation Tracker” counts 528 anti-trans bills introduced across 49 states in the first four months of 2023. This is an exponential surge since 2015-2019, when each year saw fewer than 60 anti-trans bills introduced nationwide.

A March 2023 PBS NewsHour/NPR/ Marist poll found a majority of Americans oppose anti-trans legislation, but as more bills are introduced, opposition to them is shrinking. For example, in April 2021, 65% of people were opposed to legislation that would criminalize providing gender-affirming care to minors, as compared to 54% in 2023.

“[Book bans] are able to ease in people who may feel confused by terms and identities that are new to them by making it sound like they’re just focused on books. But it’s never been about the books,” Brown says. “It’s about wanting to deny people options … forcing everyone into a cis-allo-heteronormative white supremacist box.”

While the most numerous and most successful efforts to ban books have been in Texas, Florida and other majority- Republican states, local schools and libraries also face challenges. Last June, a national group called CatholicVote launched a campaign called “Hide the Pride” which instructed parents to check out all books from LGBTQIA+ Pride displays at libraries, then announce to the library that they won’t return the books unless the library agrees to remove “the inappropriate content from the shelves.”

The campaign made waves locally when the group targeted the Rohnert Park-Cotati public library, sharing photos on the CatholicVote website of an empty bookshelf. The library called it a censorship effort against their values.

Kobabe regards book bans as one effort among many to erode public services and human rights e says have long been taken for granted. “Book challenges were step one,” e says. “The ability of trans students to be safe in schools is step two. Completely eradicating trans healthcare — including for adults — is step three.”

Steps four and five, which e fears are forthcoming, would be the eradication of public libraries and public education.

In April, the Missouri House of Representatives voted to completely defund the state’s public libraries. Their decision was a retaliatory reaction to the Missouri Library Association and ACLU suing the state over a recent law that bans hundreds of books from school libraries and criminalizes school officials who don’t comply with the law.

Kobabe worked in an academic library for ten years and is passionate about the resources libraries offer people.

“Beyond access to books, libraries are one of very few places where you can get free WiFi, use free restrooms, even sit in the shade,” e says, adding that many libraries provide after-school care to kids and help adults with taxes and job applications.

“Not having a library really impoverishes a community,” Kobabe says.

What’s next for Kobabe?

This January, Kobabe announced eir forthcoming second book “Saachi’s Stories.” Written for a younger audience than “Gender Queer,” the new book is a graphic novel written in collaboration with nonbinary comics author-illustrator Lucky Srikumar. Scholastic Books’ Graphix imprint bought the rights to “Saachi’s Stories,” which is slated for release in 2025.

Between accolades and attacks, the continued spotlight on “Gender Queer” spurred a lot of interest in eir next book. “We showed the book pitch to six publishers and ended up getting offers from four of them,” e says.

Kobabe began a draft of what became “Saachi’s Stories” before the backlash to eir memoir started. After eir first book came out, Kobabe heard from many parents of queer and gender-expansive kids who asked if e would ever release a children’s version of the book. E wanted to respond to these requests, but re-working “Gender Queer” didn’t appeal to em.

“It felt weird to abridge my real, lived experiences, and I didn’t want to redo a book I had literally just finished,” Kobabe says.

Instead, e decided to write a new, fictional story geared toward a younger audience. Like “Gender Queer,” the new story is about gender, sexuality and exploring one’s identity. Kobabe first hired Srikumar to consult on writing the main character’s best friend as a first-generation Indian-American. After reading an early draft of the script, Srikumar instead suggested the story’s main character could be Indian-American. Kobabe loved their idea and asked if Srikumar would co-author the book.

“At this point, we’ve both worked on it so much, I couldn’t tell you who wrote many of the scenes. It’s been a very interwoven, collaborative process,” e says.

Kobabe is also working on a 32-page zine for transmasculine people about the physical and mental health effects of chest-binding. That project, written in collaboration with a researcher from University of Michigan, took about a year to create. E is nearly finished and beginning to pitch it to publishers.

“And then in the gaps when I’m waiting for editorial feedback on ‘Saachi,’ I have started writing the really rough outline of a third book. It’s a fantasy story that also has queer and nonbinary characters,” e says.

Backlash to “Gender Queer” has consumed a lot of Kobabe’s time and energy, but it hasn’t slowed em down ideologically. “If anything, it made me more determined to keep writing extremely queer stories for the rest of my life,” e says.

Kobabe urges other writers not to let book bans scare them away from telling authentic stories about their own minority experiences, whether that has to do with gender, race, disability, immigration status, neurodiversity or other aspects of intersectional identity.

“The publishers I’ve spoken to have made very firm statements about how they will not be censoring or refusing to buy these books out of fear of being challenged,” e says. “Don’t let fear silence you, because that is one of the goals of censorship — to cause people to censor themselves.”

To Kobabe’s allies, e advises, “Don’t fall into despair; we can’t afford despair. We need action.”

When Kobabe shares information to loved ones about anti-trans legislation or hate acts that make the news, e tries to pair the information with a suggested action they can take. Right now, for example, e suggests supporting the ACLU, which is fighting censorship efforts. Kobabe also asks people to write to government officials to voice opposition to the recently-introduced California bill AB-1314, which would require schools to notify parents when a student socially transitions gender at school.

Despite the challenges, Kobabe feels supported and embraced in the Bay Area, especially within San Francisco’s large queer-comics community. Locally, e credits the Charles Schulz Museum with fostering a cartoonist hub. When a Virginia politician attempted to sue Barnes & Noble for selling “Gender Queer” and another book he called obscene, Kobabe says Barnes & Noble in Santa Rosa reached out almost immediately to invite em to do a book signing.

“It was a lovely gesture of support,” Kobabe says.

Kobabe excels at finding respites from the stressors in eir life. Kobabe recently celebrated 20 years of reading at least 100 books per year.

And then there’s K-pop — popular music from South Korea that has amassed international fans and inspired reality TV shows, collectible pop star memorabilia, fan fiction, choreographed dance videos and more. “I’ve made more new friends recently through a shared love of K-pop than I have through any other venue since grad school,” e wrote in an Instagram post.

“I see live music and I also spend a lot of time with friends talking about album releases and music video releases and upcoming concerts,” e says.

Even during the COVID-19 lockdown, the K-pop industry couldn’t be deterred. Kobabe says, “I saw, like, 30 concerts from my laptop in my bed. And it was great. It really gave me something to look forward to.”

In short comics Kobabe shares on Instagram, e writes about eir love of K-Pop and other fandoms. Whether writing about eir hobbies or the toughest experiences in eir life, Kobabe’s effervescence and authenticity are always apparent.

“I’ve realized how powerful it is to write your deepest truth — to say, ‘I did this,’ or ‘I felt this,’” Kobabe says. “People can argue against it, but they can’t refute it because it’s your truth and you’re saying it from the core of yourself.”