After two years of pandemic-induced numbness, where we learned to accept social distancing to keep COVID-19 at bay, U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón reminded Santa Rosa Junior College students and faculty that now is the time to feel again.

“I need those of us who are willing to be hurt, and those of us that can receive the world and notice grief,” Limón said. “I believe we would be better off if we can remember that we are thinkers and feelers and we have capacity for more emotions.”

Limón read from her expansive poetry repertoire as part of SRJC’s Fall 2022 Arts and Lecture series at the Burbank Auditorium Nov. 22.

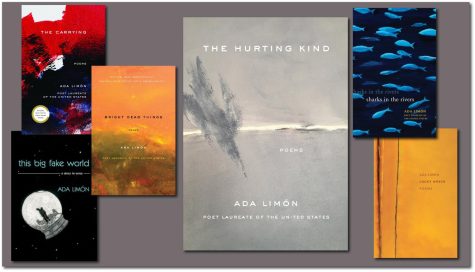

The author of six books of poetry, Limón’s latest work, “The Carrying,” won the National Books Critics Circle Award for Poetry, and her previous work, “Bright Dead Things,” was nominated for the National Book Award for Poetry, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award.

She has been a fellow with the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center and the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Limón currently lives in Lexington, Kentucky and is a poetry instructor in the master of fine arts creative writing program at Queen’s University of Charlotte, in Charlotte, North Carolina. She also hosts the critically-acclaimed poetry podcast, “The Slowdown.”

On Sept. 29, the Librarian of the U.S. Congress appointed Limón to a one-year term as the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate, a position with roots dating back to 1937. In her position, Limón serves as the official poet of the U.S. and seeks to raise national awareness and appreciation of reading and writing poetry, in the style she chooses. Previous Poet Laureates have visited elementary schools to encourage kids to write poetry or tried to make poetry accessible in airports, supermarkets and hotel rooms.

Limón drew much of her inspiration from nature around Sonoma, her hometown, and she chose to read a select group of poems she wrote about the area. “It’s hard not to just want to read all poems that have to do with home,” Limón said.

Her poem “The Contract Says: We’d Like the Conversation to be Bilingual” from a story of her father, an elementary school principal. Limón said he attended a meeting with some people who told him they didn’t want to park their car in the area because they said Mexicans were going to steal the hubcaps. Her father must have convinced them to park there anyway, because when they weren’t looking, he went out and stole their hubcaps.

“The Contract Says: We’d Like the Conversation to be Bilingual

When you come, bring your brown-

ness so we can be sure to please

the funders. Will you check this

box; we’re applying for a grant.

Do you have any poems that speak

to troubled teens? Bilingual is best.

Would you like to come to dinner

with the patrons and sip Patrón?

Will you tell us the stories that make

us uncomfortable, but not complicit?

Don’t read the one where you

are just like us. Born to a green house,

garden, don’t tell us how you picked

tomatoes and ate them in the dirt

watching vultures pick apart another

bird’s bones in the road. Tell us the one

about your father stealing hubcaps

after a colleague said that’s what his

kind did. Tell us how he came

to the meeting wearing a poncho

and tried to sell the man his hubcaps

back. Don’t mention your father

was a teacher, spoke English, loved

making beer, loved baseball, tell us

again about the poncho, the hubcaps,

how he stole them, how he did the thing

he was trying to prove he didn’t do.”

When Limón’s dad later moved from the school district, he received an award of an engraved hubcap for his act, and she remembers people hailing him “Hey! Hubcap guy!” as she would walk with him in public.

Limón gained inspiration for another poem, “The Mountain Lion,” from watching nature videos, which she likes to do “when life is pretty wonky,” she said. The video in question was a night motion camera of a mountain lion leaping over a fence at Jack London State Park. She watched it on repeat.

And once, when Limón visited from Kentucky, she told her husband to watch out for mountain lions, poison oak and rattlesnakes, which made him nervous. “It wouldn’t help that every park would have a huge majestic photo of a mountain lion,” she said as she laughed at the memory.

“The Mountain Lion

I watched the video clip over and over,

night vision cameras flickering her eyes

an unholy green, the way she looked

the six-foot fence up and down

like it was nothing but a speed bump,

and cleared the man-made border

in one impressive leap. A glance

over the shoulder, an annoyance,

an ‘as if you could keep me out, or

keep me in.’ I don’t know what it

was that made me press replay and

replay. It wasn’t fear, though I’d be

terrified if I was face to face with

her, or heard her prowling in the night,

it was just that I don’t think I’ve

ever made anything look so easy. Never

looked behind me and grinned or

grimaced because nothing could stop

me. I like the idea of it though, felt

like a dream you could will into being:

See a fence? Jump it.”

Cathy Prince, director of the SRJC High School Equivalency Program, said every person needs to read “The Mountain Lion.”

“When the mountain lion saw the fence and effortlessly jumped over it, the message for me is that anything is possible. People need to realize that they too are the mountain lion,” Prince said.

Limón also read her poem, “The Raincoat,” in honor of her mom, who painted the covers for all of her books.

“The Raincoat

When the doctor suggested surgery

and a brace for all my youngest years,

my parents scrambled to take me

to massage therapy, deep tissue work,

osteopathy, and soon my crooked spine

unspooled a bit, I could breathe again,

and move more in a body unclouded

by pain. My mom would tell me to sing

songs to her the whole forty-five minute

drive to Middle Two Rock Road and forty-

five minutes back from physical therapy.

She’d say, even my voice sounded unfettered

by my spine afterward. So I sang and sang,

because I thought she liked it. I never

asked her what she gave up to drive me,

or how her day was before this chore. Today,

at her age, I was driving myself home from yet

another spine appointment, singing along

to some maudlin but solid song on the radio,

and I saw a mom take her raincoat off

and give it to her young daughter when

a storm took over the afternoon. My god,

I thought, my whole life I’ve been under her

raincoat thinking it was somehow a marvel

that I never got wet.”

Limón said many readers refer to that piece as the “umbrella poem,” an idea which has grown on her and is how she started referring to it as well.

“So in my head I could see an umbrella [also], but there’s no umbrella,” she said. “It’s marvelous.”

Nancy Persons, SRJC Public Services Librarian and Academic Senate President, said she was extremely touched by “The Raincoat.”

“It was really comforting and exactly the thought process I go through when I think about my mother. It was just amazing,” Persons said.

SRJC dance major Lily Bromley, 26, said it was beautiful to see how generously Limón gave to the audience and was received in turn.

“We were barely three poems in and I already saw people in the audience crying, me among them,” Bromley said. “It felt special to hear her soft and confident voice warming the room, and watch her hands dance in the air as they painted images from her poems.”

After her reading Limón answered questions from aspiring artists and gave hope for an America united by emotional bonding as part of SRJC’s Fall 2022 Arts and Lecture series.

What do you do with work that you’re not proud of?

“Everything that I’ve made and thrown away or put in boxes — I will tell you I have written three failed novels that are in boxes,” Limón said. “I have learned so much from making them, but no one needs to read them. Everything that I have made has brought me here.”

Because of the way the media requires some simplification of the self in order to be understood, how do you manage to break away from what you’re expecting others to see?

“Making art is something without limitations,” Limón said. “My goal is to be able to have access to everything. For me the poem is the most free place that I can be. If I think too much about how someone may receive it or how someone might package it, it becomes already adulterated.”

What is the best poetry prompt you’ve ever gotten?

I think that one of the biggest ones that I love, which if you are writing about a particular event in your life, you look back and think, ‘What is the poem that would come before this? What is the poem that would come after?’” Limón said. “And you start looking at your work and finding out how to build on it.”

What is your message to teenagers?

“To remember that the thing that makes you strange or weird or lovely or idiosyncratic, that’s the thing that’s going to make you the most delightful as you age, and that’ll be the thing that makes your art,” Limón said.

In this time of great political division do you see poetry as a unifying force?

“Poetry can help us grieve or be joyful, and that it’s not just regionally,” Limón said. “I think poetry does a million things, but if there’s one thing it does across the board it will help you feel something, allowing us to tap in and remind us we are fully human beings.”

You vary the structure of your poems a lot. Can you describe how you go about choosing your structure for each poem?

“For me, every poem has its own form. You have to work really delicately to listen to what form that is, and sometimes it’s a matter of finding the container for a certain kind of emotion,” Limón said. “I feel so often when we’re drawn to poetry we think, oh finally, I’ve found a container for something that has been troublesome for so long within me. I really think it’s about listening to what the subjects in the poem want to do and seeing if they’ll find their own format.”

(Courtesy of Kerry Loewen)