Renowned climber and former Santa Rosa Junior College student Kevin Jorgeson has made a career of scrambling up sheer rock faces with nothing but razor-thin handholds, navigating the margin between success and a crippling injury. But whether it’s bringing the sport of climbing to a million kids across the nation or pioneering the most difficult free climb in the world, Jorgeson is always looking forward to a challenge.

“I like climbing because it’s hard. Not in spite of that,” Jorgeson said. “It’s really easy to avoid pain and seek pleasure and try to make things as chill as possible, but there is so much growth that happens at the intersection of pain and pleasure, learning to thrive in discomfort, in fear, and adversity. Climbing helps you see challenges not as a red flag but as an indicator that you’re actually going in the right direction.”

The right direction for Jorgeson these days is Session, a 23,000-square-foot state-of-the-art climbing gym he opened in July 2022 with a business partner. The project took more than five years of planning and nearly ended when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down gyms across the nation, but Jorgeson’s determination paid off. Session is becoming a central hub for fitness enthusiasts in the heart of his hometown, the place responsible for setting his climbing career in motion.

Jorgeson’s obsession with climbing begins in Sonoma County

Jorgeson, 38, has spent most of his life stationed in Santa Rosa and credits much of his appreciation to the outdoors from growing up in the area. He said his parents “gave him a long leash” and he was able to run amok through Sonoma County.

“It’s such a beautiful place that has such a wealth of outdoor recreation. You can’t help but want to be outside a bunch, whether it’s mountain biking in Annadel or climbing out on the coast,” he said. “That’s why when it came time to pick a spot to land on, my wife, Jacqui, and I chose to be back in Sonoma County.”

Jorgeson’s father, Eric, worked in the Santa Rosa Parks and Recreation Department’s records office for 33 years. Eric shared his love for the outdoors with Kevin and his brother, Matt, and took them on numerous camping and whitewater rafting trips to the Trinity River, Lake Pilsbury and Yosemite, which turned into an annual tradition.

When he was a kid, Jorgenson remembers his dad excitedly telling him he got on the waitlist to raft the Grand Canyon. Eric Jorgeson said each year he would have to send the park service a postcard to say ‘Yes, I still want to be on the list,’ which he did “religiously” for about 17 years. The waitlist finally paid off and he floated the Colorado River with his sons in October 2013.

“Rafting has a lot of similarities to climbing. It teaches you about risks and consequences, cause and effect,” Jorgeson said. “There’s a sequence to running rapids like there’s a sequence to climbing. You get the sequences wrong, you flip or fall. It’s taking the type of calculated risks that translate really well to life lessons.”

When asked about how he got into climbing Jorgeson’s answer is simple. “I never got out of it,” he said, noting how climbing is a natural urge for children, himself included. Climbing has since become part of his routine, like having breakfast every morning.

Eric said his son “was quite the monkey,” and would basically climb anything as soon as he was walking. “We’d be at a baseball game and somebody would give me an elbow and say ‘your kids on top of that backstop,’ and it’s like ‘Oh, I guess I better go get him down,’” Eric Jorgeson said.

Kevin Jorgeson’s first real experience in a climbing gym was at Vertex, which opened in Santa Rosa 1995, when he was 11. His dad introduced him to Vertex with a Christmas gift of a climbing lesson after Kevin seemed to appreciate the climbing wall at Sonoma Outfitters, a sports outlet store in Santa Rosa. “He was immediately hooked,” Eric Jorgeson said.

It didn’t take long for Kevin to start working at Vertex. “I was too young to get paid so I would belay birthday parties for Snickers bars,” he said, referring to the technique used to counterbalance a climber if they fall. Eventually, he was old enough to earn real money and progressed to assistant manager and head route setter.

“I love that place,” he said. “They raised me. The coaches, Andy and Dave Wallach, pushed me so hard, like Rocky Balboa. Tortuous training exercises.”

Climbing was his community growing up. Instead of spending time with high school classmates, he climbed. “I’m surprised they let me graduate because I would spend so much time cutting class to be outside as much as I possibly could,” he said.

His favorite places to climb in Sonoma County are along the coast, at Goat Rock and Salt Point. “You could get lost in Salt Point. The landscape is so unique and unrecognizable,” he said. If he wasn’t climbing locally, Jorgeson said he would typically be in Bishop, in California’s Eastern Sierras, trying to climb highballs — really tall boulders — that haven’t been climbed before.

After graduating from Maria Carrillo High School in 2003, Jorgeson attended SRJC to pursue a kinesiology degree, because he thought it would help him coach climbing. But he had already won the national indoor climbing championships for 18-19 years olds, and instead of defending his championship or getting a bachelor’s degree, he opted to pursue his love for highball climbing.

“That’s when I dropped out of the JC. I didn’t tell my parents and started going on road trips and pursuing a career in climbing,” he said. Jorgeson thinks he got his AA in kinesiology, but he’s not sure.

His father said he supported Kevin’s decision. “He wasn’t just a high level climber, but had excellent writing and speaking skills, and was so good at meeting people and building relationships that I knew he was going to succeed,” Eric Jorgeson said.

From highballs to the Dawn Wall

In 2009, during a 10-year vagabond road-tripping phase in climbing, Jorgeson made the first ascent of the 45-foot-tall face of the Grandpa Peabody boulder in Bishop, California that he dubbed “Ambrosia.”

“It was a dream come true. What I love about highballs is that they’re so big you can’t ignore them. They are just right in the foreground and command so much attention,” he said. “And then you see a body where it shouldn’t be, you know, 40 feet up some face of a big golden piece of granite. There’s just something so arresting about being a part of the landscape.”

But highballs are also compelling to Jorgeson because of the risk they present. He thrives on calculating the fine line between safety and injury, and mitigating that risk through laser-focused practice and training.

“I never stepped on a highball where the conclusion wasn’t certain. It’s like all the fear was whittled away through the process of rehearsing it,” he said. “You play through all the worst case scenarios in your head so by the time you do it, you’ve had such an experience of it already. All that’s left is to just pull on and do it. It’s a fun process.”

After “Ambrosia,” Jorgeson wanted to move away from highballs because he didn’t want to become a soloist, or climber who climbs alone without the assistance of another person belaying. He felt he needed not just a new project, but a new discipline.

Then he saw the 2009 documentary “Progression” with legendary big wall climber Tommy Caldwell contemplating the first ever free climb of the Dawn Wall, the sheer southeastern face of El Capitan in the Yosemite Valley, which was not thought to be possible. Free climbing it would mean going without equipment and only using ropes to protect against injury from a fall.

“It looked like the most futuristic thing I’d ever seen.” Jorgeson said. “That’s what I love to do, pull the future into the present. Look at a big thing that’s never been climbed before and figure out how to bring it into the present.”

Jorgeson asked Caldwell if he needed a partner, and Caldwell accepted. The two spent the next six years planning the 3,000-foot ascent, considered by many climbers to be the most difficult big wall climb in the world with 12 of its 32 pitches rated at 5.13 on the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) and seven rated at 5.14.

The YDS is a method for rating the difficulty for walking trails and sport climbing routes used primarily in the U.S. and Canada. A class 5 is used for climbing routes; any fall in a class 5 could be fatal. The second number is the subcategory for the climb, with a 5.1 suitable for beginners and a 5.13-5.15 the most technical climb possible without the aid of a rope to ascend.

“You spend two to three months a year on the wall, starting in October, until the snow comes, figuring out if it’s possible,” Jorgeson said. “You could describe it in stages. Early on it’s ‘Is this possible?’ Then there’s ‘Oh my god, we can do this,’ to ‘We’re going to do this.’”

Jorgeson started as the underdog of the duo, the “mentee” to Caldwell as mentor. But their dynamic shifted into a more-balanced partnership as Jorgeson improved his big-wall climbing skills.

“Moving into big wall climbing was like becoming a beginner again. Without Tommy I couldn’t have reinvented my form,” he said. “It took six years to pass the exam and be at the point where I could have any hope of getting that thing done.”

When the pair finished planning the route and felt prepared, they began their ascent of the Dawn Wall on Dec. 26, 2014. Jorgenson hit one major hurdle, Pitch 15, which took him six days and 11 attempts to pass.

“You typically started at 3 or 4 in the afternoon and made an attempt every 90 minutes to two hours.,” he said. “So I would climb until really late and throw in the towel after four attempts. Usually I’d be bleeding out of multiple fingers.”

During Jorgeson’s struggle, Caldwell had made it to pitch 20 and was in sight to finish the climb alone, but stopped to wait for Jorgeson to catch up. He wouldn’t conquer the Dawn Wall without his partner, even if waiting too long could cost him the honor of the first ascent.

Jorgeson had a good feeling on the day he finally completed Pitch 15. It was overcast, so he wouldn’t get sweaty from the sun, and it was windy, which is good “juju” for climbers. “Something in the air gets you psyched,” he said. The magic ingredient, though, was changing his approach.

“That’s what my body needed,” Jorgeson said. “Using a more time-consuming foot stance would trick my body into thinking I was asking it to do something new as opposed to the same choreography. It all clicked.”

After completing Pitch 15, Jorgeson took about a minute to celebrate before moving on. “But that’s the fun of the battle,” he said. On Jan. 14, 2015, 19 days after they began the ascent, both he and Caldwell made it to the summit to an unexpected media swarm.

Kevin’s dad said his son and Caldwell were shocked by the publicity.

“We were following it, and at some point we said, ‘We gotta get out there.’ So we packed up and drove to Yosemite, and all the media vans were lined up on El Cap Meadow: BBC, CBS and NBC, it must’ve been 25 vans all lined up with their satellite dishes. It was crazy,” Eric Jorgeson said.

Eric hiked the Yosemite Falls Trail to be at the El Capitan Summit when Kevin topped out.

After Kevin finished the climb Eric said Kevin wore a huge smile as he made his way to a huge crowd and then girlfriend and future wife, Jacqui, “He was mobbed and I had to fight through to get a hug and a quick picture before the media grabbed him,” Eric Jorgeson said.

Getting down was also an experience of a lifetime for Eric. At the summit was Alex Honnold, a famous climber and friend of Kevin’s, who offered to rappel him down the East Ledgers of El Capitan, or “climber’s shortcut.”

Eric said the rappel down was exciting, but a little scary as the day got dark by the time he was halfway down. “I thought I was going to have a heart attack and ruin Kevin’s big day,” he said.

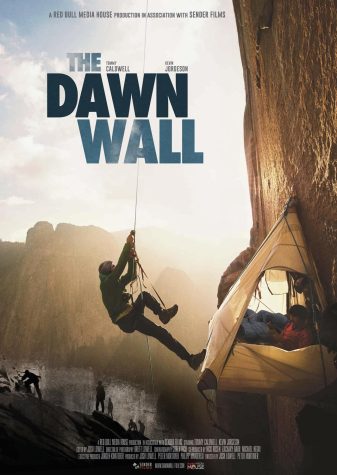

Kevin Jorgeson and Caldwell gained national fame after the Dawn Wall with an appearance on “Good Morning America” and a congratulatory Facebook post from President Barack Obama. “It must’ve been a slow news week,” Jorgeson joked. The climb was also documented in the award-winning 2017 film “The Dawn Wall.”

After the Dawn Wall ascent, Jorgeson planned to blaze another route up El Capitan with Caldwell and Alex Honnold in 2019, calling it “New Dawn,” but Jorgeson had to back out at the last minute to be with his wife, Jacqui, and son, Edsel, 4, during the Kincade Fire.

“That sucked,” he said. “We were right on the border of the evacuation zone. We live in Montgomery Village and the fire was coming over the hill into Rincon Valley. I had to come home and pack up the house and be ready to go. But I have no regrets.”

Inspiring 1 million kids to climb

It was in 2010 when Jorgeson first asked “How can I introduce a million kids to climbing?” He started by raising money for a climbing wall at the Boys and Girls Club in Sonoma Valley.

But after completing the Dawn Wall — and benefitting from his newly raised profile — Jorgeson co-founded the non-profit organization 1Climb, which built climbing walls in the Boys and Girls Clubs of St. Louis and Santa Rosa using the Sonoma wall as a pilot.

Jorgeson chose to partner with Boys and Girls Clubs since 4.5 million kids a year spend their afternoons there and the clubs he worked with were all near a climbing gym, which he says is necessary so kids can continue to climb after they grow out of the clubs. So far 1Climb has constructed 14 walls across the country with four more opening soon, one in West Oakland.

The idea behind the name 1Climb is that one climb has the potential to change a kid’s life.

“Competing gave me something to focus on throughout my teen years. I was really lucky to have found something I was passionate about early in life. It gave me a trajectory and a path I never looked back from,” he said.

Jorgeson knows a million kids is a lofty goal, but he said the point is to impact as many lives as possible over the life of the organization.

“We found a simple idea and a way to execute it. It’s just a question of funding. There’s lots of funding out there. Good ideas are scarce. Money is not scarce,” he said.” It’s a worldview that I have. To just focus on good ideas and impact and everything else will take care of itself.”

Jorgeson said his favorite days of the year are when he attends 1Climb grand openings and watches kids climb for the first time. He is also retrofitting the climbing wall at Chops Teen Club in Santa Rosa, where Jorgeson was the inaugural route setter when he was 16.

The Dawn Wall climb also sparked Jorgeson’s venture into motivational speaking; he and Caldwell never meant for the climb to be a public spectacle, but they received speaking requests while they were still on the wall.

“Microsoft wanted us to come give a talk. We’re like, ‘What do I have to say to Microsoft about anything?’ But they’re super fun,” he said. “It’s being asked to recount an experience in a condensed format in a way that’s helpful to people. In that sense I probably learned more about the climb as a result of sharing the story as opposed to just hopping out and going on with life.”

Session gym: a place to hang

Now that Jorgeson has a family he said his biggest challenge is balancing his time with them and his current projects.

Jorgeson’s climbing gym, Session, is the project that takes up most of Jorgeson’s time. Ringing truth to his words of growth from facing adversity, pushing with the construction of Session through the pandemic has paid off. People deprived of community spaces and activities during COVID strengthened their resolve to workout with friends, he said.

“I’ve had lots of folks pulling me aside saying ‘I’m so grateful this place got built. I’m finally back into yoga or an exercise routine that I didn’t have during COVID because I hate working out in my living room,’” he said. “It was brutal to take so long to build, but in hindsight things got better by the time we were ready to open.”

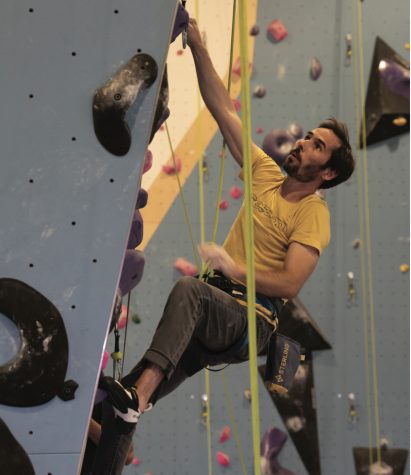

Session, located two miles south of SRJC on South A Street, has already attracted a number of students, Jorgeson said. He thinks climbing has a lot to offer students, whether it’s the process of movement as a de-stressor or to help returning to life in a post-pandemic world with uncertainties.

“Whatever you need, climbing will give it back to you like a mirror. It helps you face your fear,” Jorgeson said. “I think the more you can learn to enjoy things that push you really helps you discover what you’re capable of.”

Climbing is different from other sports, Jorgeson said, because you don’t have a coach spoon-feeding you on how to do everything. When climbers encounter a difficult section of a wall, they each have to find their own way to make it work.

“You can tell a lot about someone by watching them climb for 30 seconds,” Jorgeson said. “If their footwork is precise, what their breathing is doing and how much effort they’re exerting in their arms versus their feet. All this stuff tells you about a person’s mindset and how they approach scary things.”

Besides dealing with life, climbing is a great way for students to focus on a mental challenge other than academics, Jorgeson said. He designed Session with a lounge featuring cold brew coffee and kombucha on tap and plans to sell snacks and other light food in the future. The lounge allows patrons to toggle between work and play, a balance Joregson thinks is invaluable to any success. The gym is open until 10 p.m, which is later than most coffee shops or places to study in the area.

Jorgeson met his future business partner, Schaffer, through climbing as a teenager. Schaffer went down the academia path and became a professor, even teaching English at SRJC for a time. Schaffer was building his own ideas of running a climbing gym up in Oregon when he heard of Jorgeson’s plans for Session. “He was literally teaching up until about six months before we opened,” Jorgeson said.

The partners created Session not just as a gym, but as a place where people would be happy to hang out. Stepping into Session is like being in a climbing gym mixed into the Mayacamas Mountains, which peer through the wall-height windows and let the natural breeze rush through the array of blue, gray and tan walls that reflect the serene aesthetic of the outdoors. Even the location at the intersection of Highway 12 and 101, makes it an easy landmark to base proximity of the gym to the surrounding area.

Session isn’t just for climbers, Jorgeson said. There is also a yoga studio and a mezzanine above the lounge with treadmills, free weights and climbing-specific training equipment.

“The hope is to surround yourself with people who have shared values and priorities for how they spend their time,” he said. “We’re focused on how we can make this a place where people feel their time is well spent in every interaction, from folks walking through the door to every yoga class and every route that goes on the wall.”

Session even offers climbing routes dedicated to kids. “We added the [kid-friendly holds] on top of seven other colors so that kids will have something to do next to their parents while they’re at the gym. Kids just want to do what their parents are doing,” Jorgeson said.

Siany Escamilla, 24, a children’s climbing coach at Session and an SRJC welding student, said the gym offers kids a place to build on their natural tendency to climb walls and trees.

“Climbing isn’t just a physical exercise for them. It’s like solving a puzzle so there’s a mental exercise in critical thinking too. And the parents appreciate how it tires them out, in a good way,” Escamilla said.

One of the founding members of Session is Tyler Ripley, 23, an SRJC pre-nursing student who registered for the gym before it opened and said he’s loving his time there.

“I was a climber at Vertex before Session opened. It’s awesome to have two gyms in the area, because the community just exploded,” Ripley said. “There are so many new climbers, which have made it a really good experience for people getting into the sport.”