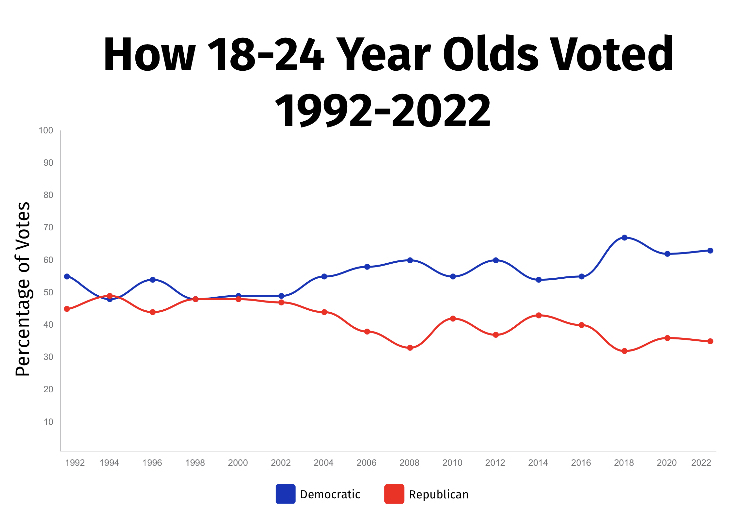

The predicted “Red Wave” was dulled to a splash by millions of young voters who cast ballots that carried progressive candidates and measures to victory in the 2022 election, reminding Americans of the power young generations hold.

Voters aged 18 to 24 have continuously exemplified their potential to change the political landscape, and the 2022 midterms were no exception. Young people shaped the outcome of close races in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Arizona, among other states, with college-aged voters electing progressive candidates at margins roughly 20 points larger than their counterparts, according to Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE).

“I tell students that they constitute one of the largest voting blocks ever,” Santa Rosa Junior College political science instructor Azamat Sakiev said. “We can see that when they participate, people really care about what they have to say.”

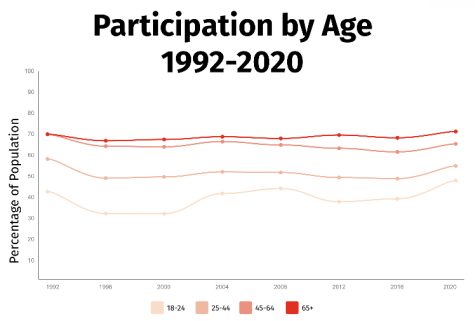

Despite possessing the ability to swing contests for the most powerful positions in American politics, young adults don’t typically turn out in numbers parallel to other age groups. For the past 50 years, only 30-40% of eligible 18-24 year olds voted in presidential elections and 20% in midterms — compared to 60-70% ballot, with concerns predominantly focused around a few major topics.

Abortion rights was the most significant issue for more than 50% of SRJC participants, following the overturning of Roe v. Wade last June. The threat of losing reproductive rights spiked voter registration among young voters and women across the country, a change reflected in the results of related ballot measures in California, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana and Vermont.

SRJC students also cited climate change and issues of social equity; these progressive-aligned issues generally ranked as more concerning than inflation.

“The current generations aren’t as materialistic as previous ones. They’re willing to take a toll on income and care more about things like racial equality and social justice,” Sakiev said. “It’s refreshing and different.”

But these ideologies might also hinder students’ engagement in civic life. Roughly 15% of students surveyed believe the political system is unrepresentative of their values and described it as “too moderate” for results to elicit systemic change.

“If you think this election won’t fix everything, you’re 100 percent right,” March For Our Lives organizer David Hogg, 22, told PBS News. “But it’s one step closer to making things a lot better.” March For Our Lives organized a 1.2 million-person protest against gun violence in 2018, and has since held voter registration drives and continued to mobilize youth to vote with gun safety as a priority.

“People are emotional creatures. Stories change minds, not statistics,” Hogg said. “We want to work together on what we can agree on — the fact that nobody wants their kids to die in their school or community, no matter if they’re on the left or right.”

Youth-related issues are often underrepresented in political campaigns; many politicians don’t target younger voters due to their perceived small impact.

“The first things politicians will never touch, which have turned into an entitlement, are things for older generations,” Sakiev said. “Politicians care about them because [older generations] do vote, and if you mess with their Medicare or Social Security, they won’t be there.”

The lack of direction toward youth does reduce students’ inclination to vote.

“It just doesn’t seem like politicians care about us,” one anonymous SRJC student said in the survey.

K-12 civics education increases the likelihood of young-adult voting

On a broader level, political science and education researchers throughout the University of California system — including those at UC Berkeley, UCLA and UC Riverside — worked with CIRCLE in 2022 and determined that to effectively raise youth voting rates, elementary, middle and high schools need to adjust their flawed curricula to emphasize civic engagement.

“Unfortunately, even teaching about something so basic to representative democracy as free and fair elections and the peaceful transfer of power is sometimes now perceived as partisan,” research director Abby Kiesa said. “In order to maintain self-governance and the rule of law, we can and should pro- mote instruction around informed and equitable voting in nonpartisan ways.”

A 2022 Tufts University study found students who learned about voting in high school were 40 points more likely to vote as 18-or-19-year-olds. College students have consistently voted at rates roughly 15 points higher than peers who didn’t attend a form of higher education, according to Pew Research Center and CIRCLE.

Fostering a culture of voting in early-learning stages would also incorporate a more racially and socioeconomically diverse demographic.

“Colleges don’t catch everybody,” Sakiev said of higher education’s ability to drive political engagement. “It has to be through K-12.”

CIRCLE’s research has repeatedly shown that teaching about elections, as well as frequent discussions regarding current events, helps students establish an informed vote. However, due to the polarized political climate and admin- istrative barriers, educators struggle to incorporate it into the curriculum.

Young voters face other barriers throughout the voting process

Other barriers to voting also exist for younger people, who face different opportunity costs with challenging schedules and financial instability. Missing a day of work is not possible for many of these voters and comes into consideration when voting lines reach six to eight hours long on election day. Learning about candidates takes free time some young voters don’t have, and the voting process is loaded with requirements that suppress youth voting, according to a study and analysis from UC Berkeley.

And if young voters traveled outside their home state for college, they might need to leverage the absentee ballot process, which can present another round of challenges. “If my signature on my absentee ballot doesn’t match the signature I registered to vote with, my ballot gets thrown out,” Hogg said, noting that voters who registered as young as 16 might not remember how they rendered their signature back then. “[Republican strategists] know that’s something that disproportionately affects younger people, who may tend to vote more progressively or against people in power.”

Still, a steady increase in youth registration, thanks to civic mobilization via social media advocacy, could continue to increase youth turnout in the future, a proposition some politicians look forward to while others deride. Some conservative pundits even proposed raising the minimum voting age to 25 after witnessing the effect young voters had on the midterms.

“The fact that these youth voters are coming in so strong in an off-year is very concerning,” Fox News commentator Jesse Watters said. “[Schools are] polluting their minds and then they grow up and they’re in their 20s and then they vote for leftists.”

Either way — whether progressives push to engage younger voters or conservatives attempt to restrict them — both reactions highlight the power young people have to shape their politi- cal environment.

“Just one person might not think they’ll change things, but imagine if you have 10,000 of that one person,” SRJC student Joseph Girmay said.

“It makes a huge difference.”