It’s hard to imagine Laure Reichek, now a little old lady, weaving down the winding roads of Chateaumeillant, through the idyllic French countryside with a bicycle and a revolver. It’s harder to imagine the order she carried with her: put the barrel in her mouth and pull the trigger should she be caught.

It’s hard to imagine, but not impossible.

It’s the little things: the way she carries herself, the look in her eye, the unmistakable French accent, her words still willful.

“You have to resist! Even though there is no hope, even though you might lose, you have to keep resisting, for your very soul, if nothing else, if you believe in such a thing. You must keep fighting because you know it is wrong.”

Laure Reichek is an 88-year-old Jewish French-American living in West Marin outside Petaluma. An avid political activist, social worker and French Resistance fighter, Laure is a regular speaker at Santa Rosa Junior College.

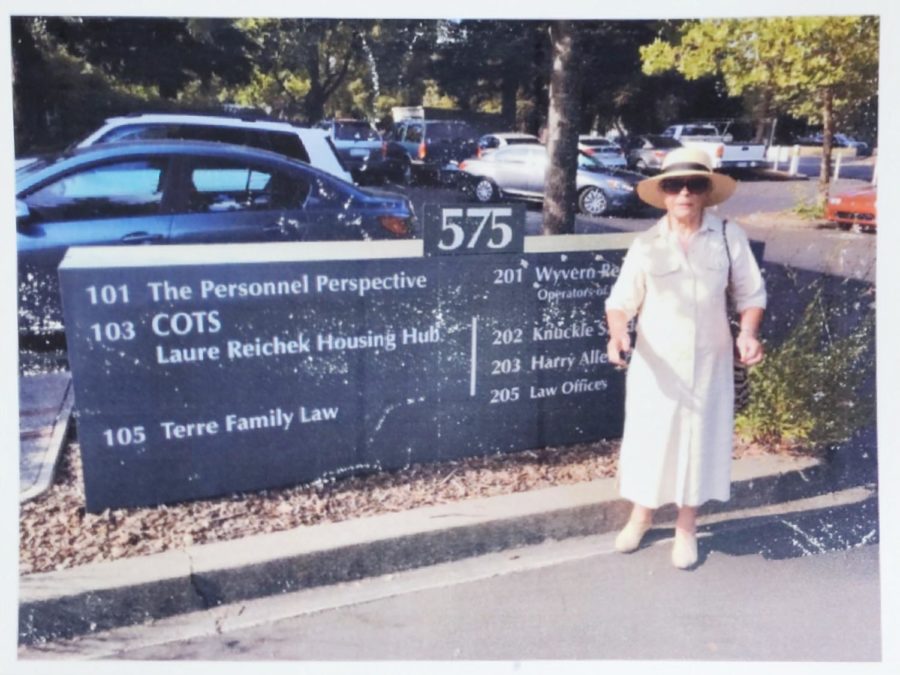

She is also one of the founding members of the Committee on the Shelterless (COTS), a local organization dedicated to helping the homeless transition to permanent housing. The COTS Laure Reichek Housing Hub in Santa Rosa honors her relentless dedication to fighting social ills in Sonoma County.

Laure was born in 1930 in the town of Chateaumeillant, France. Her Bohemian father lived in Paris on a boat without electricity or running water. Her mother, a French Canadian of Native American descent, died when she was young.

She never really knew her father, who fought against the fascist Franco in Spain with the International Brigades, ragtag band of volunteer fighters from all over the world who possessed an ideological enmity toward fascism.

Laure was raised by her grandfather, a small-town doctor working in Chateaumeillant and an avowed Socialist. They lived in a farmhouse and depended on the land for subsistence. It taught her the value of a simple life, and her grandfather taught her to be “dedicated to serving the most people.”

“Those values were inculcated in me at an early age,” she said. “This was what a thinking, feeling human being was on the Earth for. If you had the privilege of having enough food, and good shelter, and all kinds of extras, that put on you the responsibility of helping those who didn’t.”

When the war started in 1939, the German Army crossed the Maginot Line, the militarized border between France and Germany. The French were no match for the Germans’ overwhelming force. Laure never forgot the image of French soldiers running away. First went the officers in their cars; men on foot soon followed. It was “The Debacle,” or the defeat.

“I remember I was taking food for my great-grandmother’s dog, and a French soldier came and asked me for the soup. I said, ‘It’s for a dog.’ He said, ‘Yes, but I am hungry,” Reichek said.

They fed and housed him for the night. French soldiers, unable to maneuver the zigzag of village streets, abandoned an anti-aircraft gun in the village center. Bombs fell out of the sky twice, dropped by Mussolini’s airmen targeting the gun.

Laure and the children went out to pick up the pieces: the fragments, the shrapnel, broken glass and broken doors. They found a woman’s body. She still had her boots on, but her clothes had been blown off along with her skin. She looked like someone had pulled her skin off, a lifeless sculpture of raw muscle.

Thinking back to the ugliness of that time, Laure said, “It’s shocking, for the first time. The second time, strangely enough, it’s not so shocking.”

Laure witnessed things during the war that changed her forever. Her grandfather was a Resistance doctor. Men would come in the middle of the night bleeding all over themselves, begging for help.

“I saw one man holding his guts in his hands,” she said.

Laure doesn’t know exactly when her family became involved in the Resistance. These were things they did not tell children. Her grandfather had a clandestine radio in the chicken coop, where they coordinated airdrops and shared information with Allied radiomen in Great Britain.

In French, through the radio, they were told, “Dr. Scalpel is going to operate street-time tonight.”

“Street-time” was their sector. The sectors and safe-houses were separate and isolated from one another. No one could ever be sure who was or wasn’t part of the Resistance.

At nightfall, Laure and her grandfather would prepare the field with a triangle of fires, waiting for “some poor little airman from London,” to see their signal and drop a shipment of weapons and coded orders.

The orders would come in a crossword. Laure or her grandfather would listen to the radio and write in each line through all the black and white squares across each row. What came through white was the real message providing crucial intelligence on targets and the next drop’s location.

Laure’s sector did not engage in direct combat, only dealt with its fallout. Her sector’s primary designation was sabotage; blasting bridges was the norm.

As a girl of 14, Laure had a different task. “My job was to take messages to the various Resistance groups.”

She knew who they were. She knew where she could find them. She had a bicycle and a revolver “with the order that if you are stopped, you put it in your mouth and you shoot.”

Laure laughed sarcastically and said, “And no problem! No problem. Because you’re a teenager! You don’t even think you die when you die. You think you’re immortal!”

Her grandfather died on Aug. 1, 1944, shortly after a “collaborator” denounced him. Collaborators were Nazi supporters who sold out neighbors and drowned Jews in wells, Laure explained.

“So many people… so many people were in support [of the Nazis],” she said.

Nazis pulled her grandfather over and shot him on a dirt road. He had warned other Resistance members in Chateaumeillant to run for the hills. Many did not listen. Those who stayed were lined up against the cemetery wall and shot.

After the war, Resistance fighters raided the municipal buildings and found records of those who had collaborated. The head of the school, a devout Catholic, had denounced Laure’s grandfather. They gathered the collaborators and paraded them through the streets.

They shaved the heads of the women and alienated the men. Some collaborators fled or moved elsewhere. Others stayed put and got on with their lives. Eventually their memories of treason began to fade.

“Life goes on,” Laure said with a shrug.

Asked about the nature of the collaborators, Laure said, “They’re in evidence today. They’re everywhere, and unfortunately they’re the majority of the population. Even here in the U.S., it’s basically the same.”

She said the far-right forces rising in democracies today on nations’ fear of immigrants — the exact same fascists that they were all those years ago. They may have different names or different faces, but their goal is the same. Nothing has changed.

The counter to these forces, Laure said, is resistance. Her generation, “the Greatest Generation” that survived the Depression and fought the Nazis, benefited greatly from the advancement of the welfare state. They became complacent and “accumulated much more than they needed,” she said. As a result, the system responsible for their prosperity declined.

“They assumed this was going to last forever,” she said, “[Twenty-somethings] don’t have the promise that if you keep your nose clean and you work hard, you can have a bedroom house, a car and a decent job.”

The forces of reaction due to changes in demographics and the means of production are fomenting rebellion from a global order where corporations dominate. The industrial supply chains that sustain global corporations feed into a culture of consumerism that is killing us.

“Those machines are so terribly addictive,” Laure said. “People say nothing because their mind is hacked, their body is hacked and they go along like sheep to a slaughter.”

Her biggest fear is the conjunction of climate change, reactionary politics and demographic shifts happening all around the world.

“I mean, the Earth has had enough with us,” she said.

Laure worries about the damage and degradation being dealt to our natural and social systems by the same big corporate system dominating global politics. Separations at the border, police shootings, the Saudi war in Yemen, the Israeli dominion over the West Bank, Laure sees all these things as streams flowing from the same fountain: fascism.

“A very few are fighting for the last resources of the planet,” Laure said. “It stinks of fascism here, I’m sorry, but it does. I know what it looks like. People say, ‘Well nothing’s changed. It’s still very nice,’ but I don’t have to go far to see it.”

Working with immigrants and the homeless has shown Laure the living conditions of this country’s poor, conditions that “should be unacceptable in the United States of America,” she said.

“If Jesus Christ himself came to the door of most Americans, they’d call the cops,” she said.

Laure thinks the oligarchs —those who accumulate as much as possible at the lowest possible cost and make life miserable for most — have gone too far, and it’s too late to stop them.

“But that doesn’t mean we can stop resisting,” she said stridently. “Each time you allow it, each time you’re not there to hold it back, it’s coming towards you.”

She continued, “It’s going to get so much worse before your generation decides, ‘We’ve had enough.’”

But Laure made clear economic and demographic change is not the only issue.

“Until this country acknowledges its role in genocide and slavery, it’s not going to go anywhere,” she said. The problem becomes more acute as resources become more scarce, but the problem was always there.

Laure is an environmentalist. She lives an eco-friendly life in the country, with rescue donkeys (yes, rescue donkeys from Arizona) who cut her grass, and does her best not to be a consumer.

“I am in awe of the diversity of creation,” she said. “I am in love with the variety of birds and plants. There are some landscapes I would fight for, [such as] the road by which I live, the road to Point. Reyes Station. Oh, if they wanted to frack that, I’d get my gun.”

Laure lamented, “It’s just so goddamn beautiful! How dare they? And how do they not realize that the tree doesn’t need me, but by golly I need that tree!”

She added, “Hopefully they’ll still teach poetry so that kids can imagine [the tree].”

Laure worries about survival, not just the survival of the planet, but the “survival of ideals.” She worries people are losing the ability to question, to ask the deeper questions.

More people need to ask themselves, “Am I here just to consume, and then grow old, and then retire in Florida or something? What the hell am I here for?”

Laure said, “The most revolutionary thing a human being can do today is say, ‘No.’”

It is that radical capability to reject the rationale of consumption being forced upon you and the mental enslavement that comes with it.

“Because this is what a collaborator is,” Laure said. “Someone who takes the easy road. ‘Don’t tell me that. I want to sleep well tonight. Let’s go shopping.’”

What gives Laure hope and keeps her going is that she’s had the good fortune to meet people, such as her friend Therese Mughannam and all the other people who dedicate their lives to helping others.

Therese is a Palestinian American activist living in Sonoma County. She and her family fled Palestine in 1946 during Al Nabka (the cataclysm) when the UN partition between Palestine and Israel was established. Together, the two visit Sonoma County schools advocating for peace between neighboring nations, teaching students the importance of honest reporting and impartiality.

Standing before students as a Palestinian and a Jew, they make the argument that the hatred between their peoples is not as “ancient” or “natural” as the U.S. government and the State of Israel would like you to believe.

“I have always felt that Laure Reichek is a treasure,” Therese said. “In our speaking together in front of many audiences over the years, I have seen her captivate students of all ages by the power of her message about what it means to be a human being on this planet and how to live our lives with discerning minds and open hearts in service of the poor and oppressed in the world.”

SRJC Instructor Johnny Sarraf couldn’t agree more. He teaches a critical thinking and composition course on the Petaluma campus with a focus on Israel, Palestine and Middle Eastern affairs; and every semester he makes sure Laure and Therese make it to his classroom.

“Laure is an outspoken advocate for social justice, even when it is met with tremendous resistance, as it is in examining the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” he said. “She is a local treasure, and we have been privileged to hear her stories and perspectives.”

Laure downplayed her impact on people. “I yell. I yell. I do what I can, you know? It’s not enough. It’s absolutely not enough,” she said.

Therese had other ideas. “No one who has had the privilege of hearing Laure speak will ever forget her or the urgency of her message.”

Norman Astrin • Sep 28, 2019 at 2:38 am

It is what we leave to our youth in the way of ideals and tools to survive the coming global upheaval. The belief systems of our societies should change to have a respect for all creatures of this earth and each other. What Laure believes and practices sets an example to myself and others as to what we should be doing. We live in a world dominated by hierarchical international capitalism which is controlling our path toward its own destruction. The best course we have is toward an egalitarian recognition of all creatures and humanity.

WE DO NOT OWN THE EARTH; THE EARTH OWNS US!

Liko Puha • May 15, 2019 at 9:04 am

Excellent article! Thank you. I hope to hear Laure and Therese speak sometime soon at SRJC.