My brother Julian and I have completely different minds. He is fascinated by the world of 1980s VHS tapes and has shelves upon shelves of colorful cardboard boxes, while I am more of a Netflix person. He has a mysterious fear of dogs, but I welcome any that show up on our porch. He has no concept of an inside voice and chews so loud it’s as if he’s having a conversation with his bag of Doritos; I prefer to internalize my satisfaction with the infamous orange chips.

Typical as it may be for two siblings to have different tastes, hobbies and patterns, the world also treats us differently. In the eyes of society, a typical teenager experiences the thrill of driving for the first time and gearing up for their future. He’s 16, may never drive, and his education past high school is shrouded in ambiguity. The way he carries himself in public usually attracts the eyes of strangers.

The world may treat us differently, but more importantly, he sees the world differently, because he is on the autism spectrum.

Julian started speaking at age 5 and has constantly struggled with speech and social interactions. In a society where differently developed minds are seen as uncomfortable to be around, being his older sister has been inspiring, heart-wrenching, mystifying, nerve-wracking and unique.

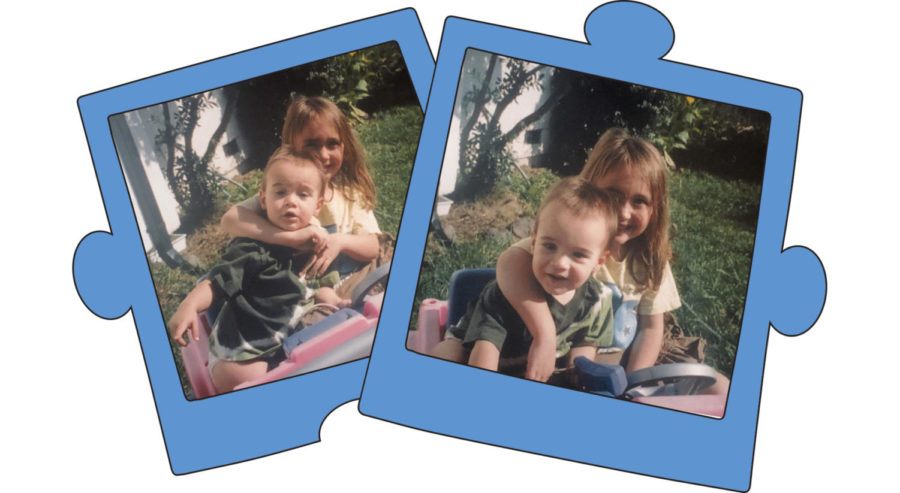

My brother and I are about four years apart, and growing up close in age to a sibling with a disability changes how you grow up thinking the world should be. I was an idealistic kid with assumptions about how our family should be, how my life would be and what I looked like to the outside world.

Over the years I’ve learned about the impact of assumptions, my brother’s educational pathway, the virtue of patience and who my brother really is. Without further adieu, I would like to share these lessons with those who don’t live the life I do.

Lesson One: Assumptions — good or bad — can hurt

Growing up with Julian wasn’t easy. Born an Aries, he was destined to be a handful, but it went further than that. He was prone to angry outbursts, which made family outings to restaurants and parks difficult and embarrassing.

What made public trips even harder were the dirty looks from mothers with their perfectly controlled children or the looks of sympathy from strangers eating their salads, pretending not to listen.

These strangers made negative assumptions about not only my brother, but also about my parents. They often categorized my mother as a bad parent. At the YMCA, she got in word wars constantly with other mothers who couldn’t understand why she was having such a hard time containing the tornado that was Julian.

The assumptions people thrust upon my parents stayed with them for years.

Now that my brother is older and has chilled out for the most part, those negative assumptions have been replaced with assumptions about how “brave” or “strong” my family and I aren for taking on this responsibility, as if it was a choice we made.

Assumptions about anyone can backfire majorly, and this applies to my brother and my family. Because of the labels that have been thrust upon my family over the years, I treat people the way I’d like to be treated: with an open ear and conversation that lacks prejudice.

The common label people have placed upon us is a “disability family.” In reality, Julian is simply someone who processes the world differently, and my family has adjusted to meet these needs.

Lesson two: Higher education is not out of the question

My perspective of my brother changes daily. I watched him learn to communicate using laminated cards with a speech therapist — and now he can hold a long-winded conversation about the game “Red Dead Redemption 2.”

His progress still throws me for a loop.

While there were times I felt he might never go to college, hindering his opportunities in adulthood, my view of this has changed. Recently, there is more room for him to grow; I know this because I’ve seen it already.

Kimberly Starke, Santa Rosa Junior College’s dean of disability resources, says there are two pathways for someone like my brother to attend SRJC, with one called College to Career.

College to Career is a three-year program that educates and trains students who need additional support to be employed in their area of interest. Program qualities include small class sizes, learning organizational and technical skills, practicing social behavior and gaining work experience— all qualities necessary for Julian’s educational growth. Starke fondly calls it a “how-to-college” program.

I didn’t know programs like this existed for my brother. While he might not want to go to college, it is comforting to know he has a legitimate choice with a great program.

Lesson three: Patience is a virtue.

During our childhood, my brother and I fought a lot. I had no concept of how his brain processed information and that in itself resulted in tension.

Julian fixated on words he couldn’t comprehend, such as the word “stop” in any other context that wasn’t a stop sign, or words such as “few” or “some” that didn’t have definitive numbers attached to them. These words caused a physical halt, and conversations would often halt in their tracks as well.

When I uttered one of these words in a context he couldn’t fully grasp, such as “stop yelling so loud in the house,” he’d begin lengthy arguments, trying to establish that “stop” strictly referred to a stop sign. At times these fixations resulted in 10 or more minutes of arguing.

As we grew older and learned from each other, these arguments began to dissipate. I realized that if I got frustrated he would, too, and nothing would get resolved.

Being able to calmly redirect a volatile conversation and prevent it from turning into an all-out war is one of my greatest accomplishments. It has helped me deal with people outside my family more compassionately.

Lesson four: Personality shines brighter than diagnosis

Some people see my brother as one thing: autistic.

It’s easy to pigeonhole him when you don’t see him everyday and get to know him, yet it is also important to realize that he’s a person who feels deeply.

Another assumption I’ve discovered is many people believe that it is hard to connect with someone who has autism because they have a hard time outwardly expressing their feelings. My mother often says Julian’s autism is a handicap, but highlights a fact that most people don’t realize: There’s a person in there trying to get his message out.

Julian is a masterful VHS collector, with hundreds of titles organized methodically on the shelves in his room. Movies such as “The Sandlot,” “The Little Rascals,” “Home Alone” and “Shrek” sit proudly along his wall. He’s even started his own YouTube channel to share his collection with the online community, but he’s very secretive about his favorites, refusing to even share that information with me.

Julian also likes to cook. Unlike me, he’s brave in the kitchen and will put slabs of meat right on the skillet and hope for the best. His go-to meal is ramen noodles with chicken concentrate for less sodium than the provided flavor packets.

Above all, Julian is fearlessly himself and the most honest person I know. Never in his life has he questioned his significance or dealt with the self-esteem issues that took me years to work through.

While sometimes he can be so honest it hurts, like when he notices me being emotional and loudly announces “Riley is crying!” he’s coming from an inherently good place.

I often think of conversations with my brother as a nice break from the conversations I have with other people. Our communication is far from perfect, but it’s refreshing to speak to someone who doesn’t care for small talk and is honest about whether or not he cares about the conversation we’re having.

People often don’t see the nuances in disability, and they choose to turn their nose up when confronted with something different. I can understand, because if Julian wasn’t my brother, I might think along the same lines.

Every person who has autism is different in how he expresses it. Experiencing his mysterious mind up close has caused me to think differently about human nature.

To his credit, Julian has the strongest sense of self I’ve ever witnessed. Yet for someone like me, though, someone who’s worked hard to erase rigid ways of being from my brain, it’s going to take my entire lifetime to grow and transcend my ideas on human nature.

I’m hesitant to not be polite in every possible moment, and sometimes when I try to voice my opinions it’s as if a small mouse has taken residency in my vocal cords. Julian has never suppressed himself in this way, and I wish I was more like him.

As a society, we reduce everyday activities and communication to black and white. The biggest problem with this is it leaves no room for people like my brother to live in grey areas without criticism.

The best lessons one can learn involve speaking with people who are completely different from themselves. Luckily for me, I didn’t have to search far to meet Julian.

In the words of Maya Angelou, “We can learn to see each other and see ourselves in each other and recognize that human beings are more alike than we are unalike.”