Dana Gioia, former professor, California Poet Laureate and chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, never wanted to be any of those things.

He wanted to be a poet. So much so that he decided to quit his graduate program in comparative literature at Harvard University. All of his professors tried to discourage him from quitting. Except for one: Elizabeth Bishop.

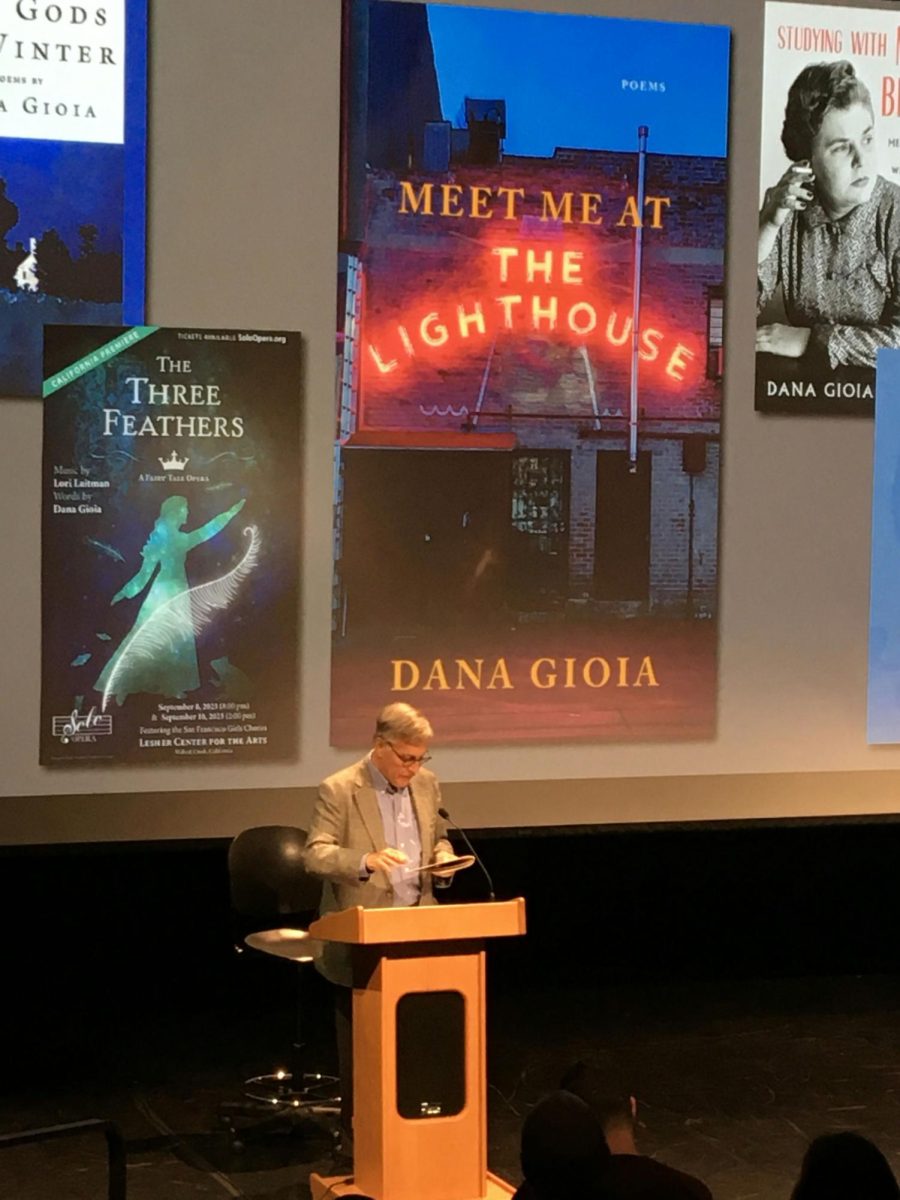

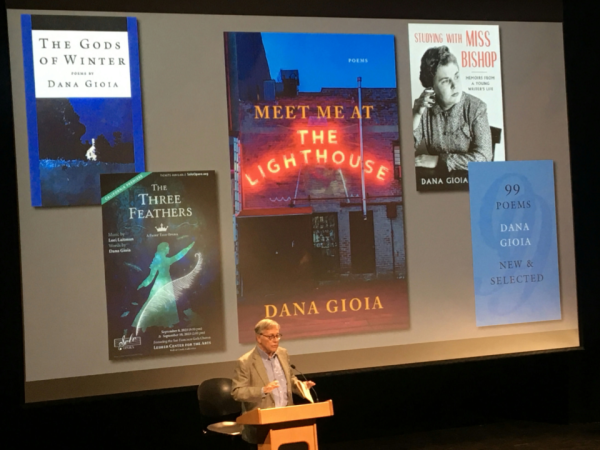

Elizabeth Bishop taught creative writing and had not yet attained international renown for her poetry. “She said [to her then-student Gioia,] ‘You’re really smart to get out of here,’” Gioia said to the audience gathered in the Frank Chong Studio Theater to listen to him read his poems and answer questions on Thursday, March 28.

The event started with high school students reading their own poetry. It was briefly interrupted by a person who crashed the event to recite his own poetry (“and a strange poem it was,” Gioia said afterwards). Then Gioia read his own poems, many new ones from his book published in 2023, “Meet Me at The Lighthouse.”

Gioia read his poems to a rapt crowd of about seventy-five attendees. Although community members comprised about two-thirds of the audience, students also attended.

Gioia writes poems that people can understand, a literary decision that made him a “controversial figure,” he said. He uses familiar words, recognizable rhythms and rhyme schemes. He invokes an easy, earthy sensuality in his poems, and writes about everyday realities, from tweeting teens, to bar brawls to “the musk of [his wife’s] dark hair.”

Gioia said he “wanted to write poems that people experienced,” speaking of himself as a young poet while studying at Harvard. Decades later, this desire continues to motivate him. “The lives of poor people vanish,” Gioia said in preface to “The Ballad of Jesus Ortiz,” a true poem about his great-grandfather based on documents he received from the state librarian of Wyoming.

With a simple rhyme scheme, the ballad moves steadily forward through time to describe the hard-knock life of Jesus Ortiz, a vaquero who “never had a bed” and “lived in dugouts, or shacks of pine and tar,” in a town where the “biggest [building] was a bar.” Gioia chose the ballad form and this easy rhythm so that this forgotten story could be preserved and passed along, an intentional reanimation of this borrowed form.

During the questions, when an audience member asked Gioia which poets he reads, he rattled off a list of about a dozen poets from Frost, Auden, Yeats and Wordsworth to Philip Larkin, pausing to recite Larkin’s “This Be the Verse” before moving on to Catallus (in Latin and then English). Gioia switched smoothly between centuries, to summarize, “I think everybody should have half a dozen poets and put them in your roster, as they say on dating sites.”

Gioia never applied to become poet laureate because he was too controversial, he said. “I write poems people understand, and I give honest reviews, which means they’re not positive.”

Bob Stanley, a Sacramento poet, and his student, Breanna Hardy, nominated Gioia for the poet laureate position. But Gioia resisted making the two-hour drive to the interview until his wife mentioned a nesting white-faced Ibis they could look for near the interview held in Sacramento. When he was awarded Poet Laureate, he decided to visit all 58 counties in California, something no laureate had ever done before (or since).

In each county, Gioia created a little festival to celebrate the creativity of the place with local poets and musicians who performed alongside. His favorite stop was in Downieville (population 300, elevation 3000-feet) where every school-age child recited a poem and asked real questions, such as the name of his cat and his birthdate.

Gioia didn’t want to be chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) either. “To the Right, the NEA were purveyors of smut and blasphemy. To the Left, they were inept purveyors of smut and blasphemy,” he said. However, he accepted the position and made it his mission to reinstate art programs that were being canceled all over the country. “You don’t have the arts [in schools] to produce professional artists,” he said. “You have arts in schools to produce complete human beings capable of participating in society.”

To counter the lack of available funding, he asked himself, “What’s the cheapest art?” Poetry.

Not surprisingly, he encountered pushback. Forty-nine states said, “We don’t want to do this. Teenagers don’t like poetry. Memorization is repressive.”

He created a poetry contest, and people responded, “It’s degrading to do art for competitions.”

But his efforts have paid off. “Today, poetry is the fastest growing form of art in the U.S. and among young people, it’s doubled since NEA began the Poetry Out Loud Competition,” he said.

Poetry does matter, it turns out.