When Dr. Lena McQuade, a professor of women’s and gender studies at Sonoma State University, received an email announcing the administration’s plan to cut several majors, programs and departments in response to the university’s $23.9 million budget deficit, she felt like she was reliving the past.

Last semester, McQuade and other SSU faculty received a similar email that detailed the school’s plan to make a different cut — to one of the last remaining old-growth redwood trees on campus.

Harnessing the lessons of advocacy outlined in the WGS curriculum, McQuade implored facilities management to reconsider, citing the impact the tree’s historical roots had on shaping the university.

Though the tree was spared, the axe still swung, and on Jan. 22 the women’s and gender studies department was slashed by the blade. Since then, students and faculty have been forced to watch their own historical roots be pulled from the ground, day by day.

“I feel like I’m attending my own funeral, but I’m alive,” McQuade said.

Since its establishment in 2001, about 450 students have graduated with WGS degrees, and 15,000 have taken WGS classes as part of their general education requirements.

The department’s impact branches beyond its four faculty and 70-plus current majors and minors. “Women’s and gender studies has a huge influence on the community,” said SSU Provost Karen Moranski during a meeting with the College of Humanities, Social Sciences and Arts faculty in March. “One of the biggest impacts of [the cuts] is that it is going to impact our ability to help people feel safe, and that’s terrible.”

Beyond classes, the department provides a canopy of comfort for students who often feel ostracized in other spaces.

WGS senior Eloira Smith, 25, said that WGS allows them the freedom to exist without explanation. “I’ve spent my entire life having to justify my needs, and I don’t have to do that with them,” they said. “I don’t have to justify being.”

Even those outside of the department benefit from the faculty’s commitment to compassion. Non-WGS students seek support from WGS professors when they don’t feel safe talking to other resources, Smith said. “They don’t just make WGS a better place, they make the whole campus a better place.”

Faculty members Dr. Charlene Tung, Dr. Patricia Kim-Rajal and department chair Dr. Don Romesburg join Dr. McQuade to form the heart of WGS.

After working together for 16 years, according to McQuade, the faculty have created a home in the hallways of the Stevenson building. “You don’t go missing under [the professors’] radar. If you’re gone for a class, they’re messaging you and seeing if everything’s OK,” said Xochilt Martinez, WGS senior and social media manager of the department’s student-run club. “They become more [like] family.”

After a combined 50 years of impassioned dedication to Sonoma State, WGS faculty learned about their department’s elimination the same way they learned about the near-elimination of the redwood tree: via mass email.

The administration has not contacted any member of the faculty individually, according to Romesburg and McQuade.

This lack of communication is contradictory to SSU Interim President Emily Cutrer’s claim that the administration attempted to do the “least amount of harm” to students and faculty as possible, Martinez said.

The announcement of the budget cuts came just two days after the inauguration of President Trump and amidst a series of executive orders targeting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs.

“This is the worst time for something like this to happen,” Martinez said.

The WGS department disproportionately teaches women of color, as well as LGBTQ+ students, neurodiverse students and students who have survived sexual assault, Romesburg said.

“By singling out WGS, whether [the administration] intended to or not, they singled out two LGBTQ+ faculty, two women of color faculty, and three women faculty,” he said.

Students in these communities were relying on their school to shelter them from the storm unleashed by the Trump administration, but they now feel the administration left them in the cold.

“This is my one thing, my one safe space,” said WGS junior Mallory Field. “They cannot take this away from me.”

SSU administrators knew there would be holes in the community as a result of the cuts, Moranski said.

“I know students are being harmed by what we’re doing,” Cutrer said at the meeting with HSSA faculty. “You think I don’t know students are being harmed?”

Abandoned by their administration, students turned to on-campus groups like the WGS Club and the Queer Student Alliance for support.

Vera Lubbs, president of the QSA, said she is concerned about the club’s future now that its educational backbone has been broken.

“[The QSA] should be primarily support and a space to feel comfortable,” she said. “It should not be on the student leader to be in charge of [education].”

Shawn Ramus, president of the WGS Club, said the department teaches the kind of community organization students are engaging in. “All of us can’t do everything. Those of us who need to [can] take a step back and [know that] others will pick it up.”

WGS alumni, along with students and community members, have exemplified the importance of these lessons by organizing protests, creating websites and petitions and writing letters defending the department’s right to exist.

“The only bright spot in all of this is seeing how powerfully our alumni and students have taken the lessons of women’s and gender studies and know how to operationalize it into fighting for us,” Romesburg said.

Martinez said that WGS doesn’t have a choice but to organize. “[The administration] is not gonna hear my cries. They could care less,” she said. “They gotta see action, they gotta hear the voices.”

Still, a sense of sadness permeates through the plethora of support. “[We know] we may not ever get to do this again for other students,” Romesburg said.

Despite the administration’s efforts to pull them out, the generational roots of the WGS department still hold strong throughout Sonoma County.

The WGS major at SSU is the only in the California State University system that requires an internship to graduate. Each student majoring in WGS must contribute at least 45 hours of service to a local organization. In total, the department has amassed more than 30,000 hours of social-action oriented community service to local groups like Verity, Face 2 Face and Positive Images.

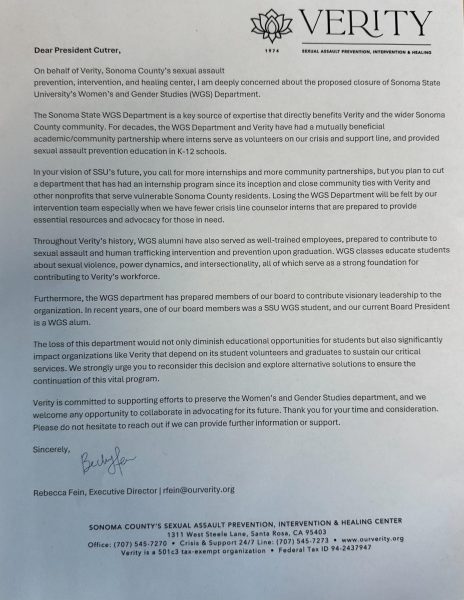

Verity, Sonoma County’s sexual assault prevention, intervention and healing center, relies on WGS students to staff its rape crisis line, Romesburg said.

“The loss of this department would significantly impact organizations like Verity that depend on its student volunteers to sustain our critical services,” said Verity’s Executive Director Rebecca Fein in a letter to SSU administration.

Verity is one of many organizations that have grown to depend on WGS interns over the years. “Funding is really difficult, so they rely pretty heavily on volunteers,” Smith said of Face 2 Face, a nonprofit group that offers free and confidential HIV services.

Ripping the WGS department from the soil will destroy the ecosystem of the Sonoma community, which has grown around and with the program since its establishment decades ago.

“All of the quantitative arguments that are being marshaled to justify our demise are not fully capturing that when this is gone, a huge thing is gone,” McQuade said. “An old-growth redwood tree is gone.”

For now, the WGS department will continue to prove that roots only grow stronger with time. “I have never known the depth of our power like I know it now,” McQuade said. “I have never been more clear about what I’m capable of and what I have done.”

Romesburg is hopeful the department will be shown the same mercy as the tree.

“We’re still fighting, and we are determined to win,” he said.