It’s going to be a small, relaxing party. No need to bring anything special. There will be some alcohol and cannabis. It should be a good time.

That was the plan, and that was the vibe… before the panic started. Thankfully, one Santa Rosa Junior College Student knew what it could mean to be prepared.

Anna*, who requested that The Oak Leaf not use her real name, thought it would be like any other New Year’s Eve party. About 30 people gathered that evening on a San Francisco beach. They ranged in age from 16-20.

The sound of the waves provided a back-beat for the conversation and laughter. The excitement had started to build. Midnight had nearly arrived. That was when a young woman at the party suddenly lost consciousness.

“It was calm. And then it wasn’t calm, and people started screaming for Narcan,” Anna recalled, “People were smoking weed and drinking, but we didn’t know that anyone was doing hard drugs.”

It could have been the beginning of another tragedy. It could have been the loss of another young person’s life. It could have been another short chapter in our country’s struggle to deal with harmful drugs. Thankfully, what once was a silencing stigma is being slowly replaced by a drive for education, outreach and harm reduction.

In Anna’s pocket was a bottle of Narcan nasal spray. Her friend also carried one that she provided when they met up to go to the party. She did not think that she would need it, but noted that now she is always prepared when she goes out. “I don’t trust teenagers to not do drugs,” Anna said.

They handed over both bottles and watched with other horrified partygoers as another young person there administered the first dose to the girl. She woke up. And then she passed out again. After the second dose, she regained consciousness.

“She wasn’t really doing well after the Narcan, she was hunched over and on her side and not very conscious, which was scary.”

Not only were most of the people at the party completely unprepared to deal with an overdose, but they were also reluctant to call authorities because they feared there would be legal ramifications.

Anna was prepared because of the harm reduction outreach, education and materials provided at SRJC. Student PEERS and volunteers from the Students for Recovery Club have presented in classrooms and the dorm since the fall 2023 semester. They bring fentanyl test strips and Narcan, and provide students with practical guidance on how to use both.

Tova Esbit, a student PEERS member and a Student Health Services intern, said her primary focus of learning has been co-occurring disorders. She believes the historically accepted method of treating substance use disorders and mental illness separately is far less effective than treating them as co-occurring issues. She has been driven to enter the classroom and speak to students since she took a psychology class that did not address the topic of addiction.

“I wanted to focus on general classes, rather than just people in recovery,” Esbit said. “I think the people in recovery typically have some knowledge there. It’s about the general students who are just hanging out on the weekends, just having fun.”

Esbit, Dan Lionett, Kenny Hotchkiss and others from the Students for Recovery club have worked tirelessly, with the help of SRJC administrators and community organizations, to provide the harm reduction materials, along with an inclusive space where students can talk about addiction, recovery and mental health.

Anna has attended the Students for Recovery Club. “Every meeting has an intro thing that says, this is not just for alcoholics and drug addicts, but it’s also for sex, love, gambling, porn, eating disorders, behavior addictions,” she said. “It says that we’re very accepting of people who are getting off of meth or heroin. Being in college and being in recovery so young is really hard, but when other people see that it makes them more willing to reach out.”

Lionett, Student for Recovery president, pointed out that people cannot be forced to accept help, and for many it is still easier to rely on substance abuse as a coping mechanism.

SRJC has participated in California’s Narcan program since before the pandemic. The school is required to supply Narcan and information regarding its use during orientation. Student Health Services Director, Rebecca-Maria Norwick, knows it can be difficult for students to understand how to access the healthcare system, but that students tend to trust the school and its health center. “With the hire of a student intern [Tova Esbit], we have significantly increased our outreach and number of [Narcan] doses given out,” she said.

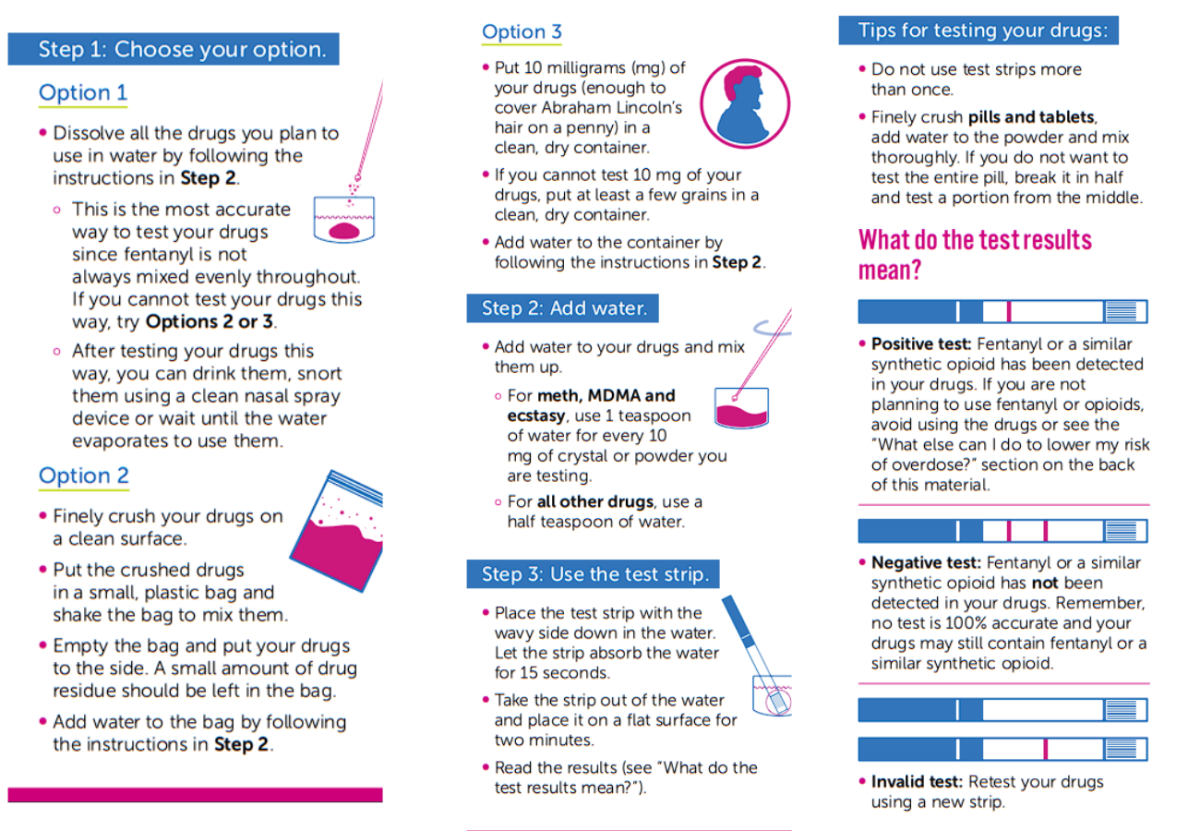

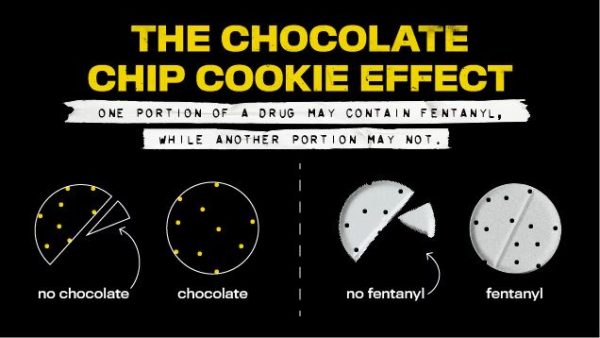

Part of the education and outreach Esbit and others provide are demonstrations of how to properly use fentanyl test strips. There is not a specific taste or smell to fentanyl, and it is not necessarily dispersed throughout a pill, so the testing must be done comprehensively and with care. Face 2 Face, a Sonoma County non-profit organization, originally supplied the test strips before the state Narcan program expanded to cover them. Now SRJC can order them for free in large quantities, Norwick said.

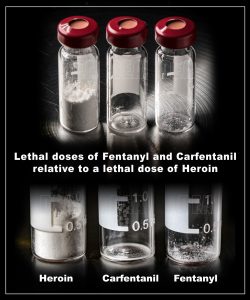

In a report released May 9, 2024, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram said, “The shift from plant-based drugs, like heroin and cocaine, to synthetic, chemical-based drugs, like fentanyl and methamphetamine, has resulted in the most dangerous and deadly drug crisis the United States has ever faced.”

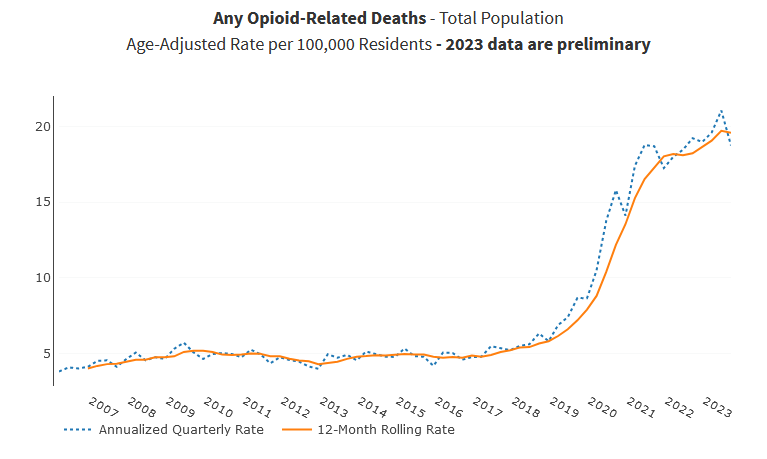

The California Department of Public Health maintains a webpage with overdose data. In 2022 there were 7,385 opioid-related deaths in the state. Over 87% of those deaths were related to fentanyl. A potentially fatal dose of fentanyl is much smaller than that of drugs like heroin.

The outreach and education taking place in the classrooms, dorm and club meetings also covers the protocol of what to do when a crisis does occur. “I should have called for help immediately, but people didn’t want me to, so I hesitated,” Anna said. “They didn’t want to get in trouble. I was trying to tell them that there’s laws that protect you. You can’t get in trouble for calling for help for an overdose.”

She may have hesitated, but she made the call, and when first responders arrived, she helped them find their location on the beach.

“Emotionally, I don’t think I was prepared,” she admitted. “Calling for help, I at least knew it was a thing I needed to do.”

Data shows that the number of overdose-related hospitalizations and deaths has declined from the peak in 2022, but that they are still much higher than before the proliferation of fentanyl. The situation may be gradually improving, but there is a persistence to the social stigma that keeps people from communicating openly about safe drug use.

Over the last two years, SRJC began to provide the outreach, education and harm reduction materials that can eventually replace the stigma with a culture of communicative support. SRJC administrators, student employees and student volunteers have worked together to build a program that offers students the basics of what to do in drug-overdose emergencies, as well as the tools to prevent them.

As Anna can testify, one young woman may not be alive today were it not for a small number of SRJC staff and volunteers driven to help those who struggle with addiction and those who may not have been prepared to experiment with drugs safely and responsibly. The experts say more lives can be saved around the nation as harm reduction programs are expanded to provide the people on college campuses exercising this radical empathy with the resources they need to bring this imperative, potentially lifesaving support to others.