Pandemic leaves children behind in social development skills

May 1, 2022

The first time that Lyndsay and Ray McClintock saw their daughter struggle socially was at their local park. They noticed that 1-year-old Delilah would see other children playing yet she played alone. She showed no interest in the other kids.

Delilah was born in the year 2020, two months into the coronavirus pandemic lockdown. She didn’t have much interaction with anyone but her parents for her first six months. Delilah struggled socially early on in the pandemic because of the lack of interaction with people other than her parents. “If she did have any interaction, people were masked.

The pandemic created social development challenges for children of all ages, from newborns to high school seniors.

March 13, 2020, a day that will forever be ingrained in the memory of students nationwide. It’s the day the President of the United States declared a National Emergency concerning the Novel Coronavirus Disease outbreak. For some, it was their last day in school. For others, it would be their last day of middle school, high school, or school at all. For all students, it was an abrupt ending to the school year.

The Covid-19 pandemic came as a shock for everyone, but especially for high schoolers. Students were immediately cut from their teachers’ hands-on curriculum and the daily social engagement between classmates. According to the Center on reinventing public education, schools typically do a poor job of offering support for students’ mental health and teaching social-emotional development.

Ray McClintock, a history teacher at Terra Linda High School saw first hand how the pandemic impacted students socially and academically.

“Kids are struggling socially by not regulating their emotions well,” Ray McClintock said. “There’s also a level of immaturity that is present from students who came in as freshman, because due to the pandemic, they essentially missed all of their social-emotional development in junior high. Especially with the boys.”

Once students returned to the classroom, Ray McClintock pointed out a sense of awkwardness in the classroom, a lack of socializing among peers. Over the course of the 2021-22 school year, Ray McClintock tried to incorporate more group projects to help students socialize with each other.

“It is hard for them to sustain long-term projects,” Ray McClintock said. The biggest problem he noticed over the academic year is students seem content with being by themselves. “Several kids hang out alone during breaks in my classroom, whereas before they would hang out with friends,” Ray McClintock said.

Terra Linda high school is actively trying to combat the regression in students’ social-emotional development. “The admin established a culture of giving kids leniency, and watching over mental health and [putting] wellbeing first and academics second,” Ray McClintock said.

The Covid-19 pandemic’s broad impact is well known, but one of its biggest effects is the social development of younger children and newborns.

Schools try to address social deficits

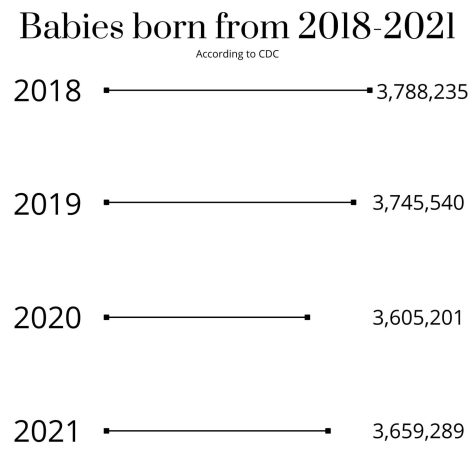

Couples who were expecting going into 2020 were faced with the impossible task of preparing for a newborn in the pandemic’s jumbled confusion. For the United States, 3.6 million babies were born in 2020, according to the CDC.

“Having a first child in general is scary, but you add an unknown of a pandemic while they are a newborn, and it was terrifying,” said first-time mother Lyndsay McClintock.

Lyndsay and Ray had to prepare for Delilah’s May 2020 birth without any help from family members or friends. Lyndsay and Ray chose to wait until Delilah was six weeks until they let another person hold her. “Ray and I constantly felt like we needed to shield her from everyone and everything,” Lyndsay said.

But, luckily she got to be around Ray and I 24-seven so we were able to still show her expression and she could see our lips move to help understand sound and formation of our mouth to speak,” Lyndsay said.

To combat the social deficits Lyndsay and Ray saw in their newborn daughter, they implemented different techniques to help Delilah further her development. “When we would walk or drive her anywhere, we would always explain to her the things we saw and colors we saw, which helped her to identify her surroundings even though she was cooped up in the house a lot,” Lyndsay said.

The first time that Lyndsay and Ray saw first-hand that their daughter struggled socially was an instance at their local park. Lyndsay pointed out that Delilah would see other little kids playing yet she would play alone. She showed no interest in playing with other kids.

Lyndsay worried that Delilah hadn’t socialized enough in her life because of social distancing. However, as time had passed and Delilah became more comfortable with other people, she began to catch up on her social skills.

Lyndsay and Ray chose a cautious and steady approach to Delilah’s social development, after not having very much interaction early on in her life. But with the pandemic on the decline, Delilah’s ability to socialize is right where it should be for her age.

“The biggest problem raising a newborn in a pandemic has been the toll on mental health for both parents. The mental load of raising a newborn in a pandemic was nothing I could ever have prepared for,” Lyndsay said.