Open Zoom. Click. Login to Canvas. Click. Find theGoogle doc. Click. Wait, check Facebook. Click. Link to Youtube. Click.

Joseph Sapp spends another day staring at his computer screen. One moment he’s focused on class and homework, but with a half-inch move of his mouse — and click! — he’s entered the mire of social media and shopping that could suck up either 10 minutes or hours of his time. Sapp knows that if he gives in, his homework will pile up, he won’t exercise and he’ll waste another night slogging in digital quicksand. He clicks anyway.

Sapp, a 37-year-old communication studies major, enrolled in Santa Rosa Junior College after losing his job as an event crew chief in charge of setting up and dismantling gaming conventions due to social distancing requirements that prevent large gatherings, the lifeblood of his industry. He had spent most of his adult years traveling around the world for his job, and suddenly he was going nowhere. Now, nearly a semester into online education, Sapp struggles to stay motivated with classes while stuck at home.

“You always have the devil on your shoulders. There’s always a way to convince yourself how to not do it,” he said.

Sapp is one of the many SRJC students — and millions more across the country —who struggled this fall to stay engaged in online education, in part because of their disrupted school routines and social lives. The New York Times and numerous publications nationwide have documented how students of all ages fell behind in coursework and saw their grades sink along with their motivation. Sonoma County educators hosted emergency summits in October and December to deal with students’ plummeting grades and anxiety about the future.

While many SRJC students don’t find the prospect of online education ideal, many were prepared to make the most of the fall semester only succumbing to apathy instead.

“When you make yourself do something at a time you don’t want to do it is when it feels the most rewarding afterwards,” he said.

However, some students are numb with despair. They are in “fight or flight” mode

because of the threat of COVID-19, said Liya Levanda, a graduate level therapist at student psychological services, at a Santa Rosa Junior College PEERS workshop titled “Motivation and Mental Health.”

In the “fight or flight” response, the brain releases the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, which decreases activity in the prefrontal cortex, the main area involved in creativity, planning and complex tasks. This makes sense because humans evolved to handling acute dangers, such as running away from a predator, and planning takes time. However, students have lived with the pandemic for nine months now.

“Your brain is operating in a mode that is not sustainable,” Levanda said.

Norepinephrine increases activity in the amygdala, which is responsible for emotional processing. This could be why the fear of COVID-19 seems everpresent, even if you’re being safe, and why the “fight or flight” mode persists.

Students living in “fight or flight” mode for prolonged periods of time can succumb to learned helplessness, Lavanda said. A state when someone feels they are in danger, but any effort to fix it would be futile, and they give-up. Learned helplessness could lead to apathy and unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Sapp’s moment of learned helplessness came after losing his job. He applied to 30 positions, but didn’t hear from any of them since work is limited during COVID-19. Compounded with fires and political unrest, Sapp retreated from the world, coping with food and video games, until he found himself in a hole.

“It’s like putting on a weighted blanket, and then stack more on top of that, and that comfort you were seeking at first becomes cumbersome,” he said.

Sapp realized he needed to move on to ‘plan B’ and signed up for fall classes. While most students were uneasy about starting a semester online, Sapp saw it as a fresh change, but by the middle of the semester, after multiple days spent staring at a computer screen, the shininess wore off.

“I thought it was so cool at first, but then I wasn’t sure. There’s this wall you hit,” Sapp said.

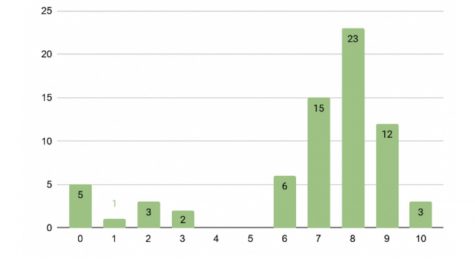

Sapp’s apathy is not unique. University of Colorado Boulder conducted a survey asking students nationwide to rate their motivation before and after the transition to online education. On a scale of 1-10, 59 out of 70 students rated their motivation before the transition as 6 or above, but this dropped noticeably with 57 students rating it as 4 or lower.

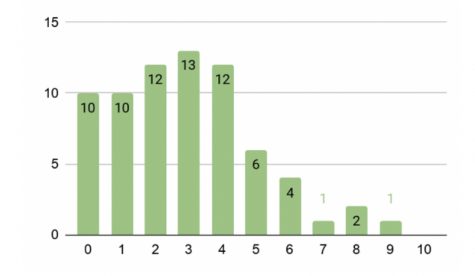

In a more local version of this survey, 47 student-attendees were asked at the PEERS workshop to rate their current motivation levels on a scale of 1-10 with ten being super-energized and 1 being depressed in bed. The majority answered between one and four.

Tyler Shatto, 26, an SRJC civil engineering student, said he started the semester with a lot of motivation but not being able to work with his peers in person, such as on campus or at the library, has been challenging.

“Not necessarily on the same subject, but having somebody chilling with you who you could shoot the shit with for a couple of minutes and reset a little bit,” he said.

Now that he does everything from home, he resets with social media, which is harder to budget time for.

“It’s so easy at home to sit on the couch and watch YouTube or something for a 10-minute break and the next thing you know, it’s been an hour or two,” Shatto said.

This is the first semester that Shatto habitually begins assignments the day they are due, rather than starting them in advance. Instead, he now has to crush assignments for 10 hours straight instead of 2 hours a day for the week. Shatto feels he has learned less by studying this way.

“It’s not what I set out to do, but it’s just how this semester has gone,” he said.

Shatto says that creating a schedule that works for him has helped him gain the motivation to finish his classes strong. He dropped the repetitive monotony of social media, and embraced video games which are new and exciting for him. For Shatto, video games are the carrot that drives him through his assignments.

“Having something that I really wanted to do, but then restricting that until I met some sort of threshold of work done gets me to finish it,” he said.

Sapp said the fear of falling behind is what kept him afloat during the mid-semester lull, but he regained his drive to learn by maintaining a strict schedule for diet and exercise.

He said it was hard at first to leave the house for his 8 p.m. walk, because after a full day of online education he would be weighed down by indoor comfort. But on the nights he forced himself out of the house, Sapp felt the most rewarded; now he looks forward to his hour-long walk six days a week.

“In order to have success at anything, it has to become routine,” he said.

Levanda said it is important to make time for mental wellness such as exercise or simply breathing in the fresh air.

“These are all things that are still an important part of your daily life, and it’s easy to forget them when we are sitting at our desks all day,” she said.

Rafael Vasquez, an SRJC instructor and outreach coordinator for Extended Opportunity Programs and Services who also spoke at the Motivation and Mental Health workshop, agrees that a schedule can help students stay motivated. For students who procrastinate, Vasquez recommends what he calls the 15-5 system, which is to study for 15 minutes and then take a five-minute break.

“Dividing the work keeps you motivated so that it’s small pieces of work that you are doing instead of that one 10-page assignment,” Vasquez said.

Levanda mentioned the Zeigarnik effect, which suggests people keep unfinished tasks in their mind more than tasks they haven’t started, like how TV cliffhangers keep watchers interested in shows. This idea compliments the 15-5 method of studying.

Michelle Knutson, 26, a natural resource management major, said she enjoys her classes, but still has trouble staying engaged during long Zoom lectures.

“My screen time on my cell phone went up during class, which I couldn’t do in person. It’s just so easy to pick up and look at, and then you mess around with it,” she said.

Kuntson said that she is more motivated to learn when instructors discuss the material covered before and after lectures. She said that she doesn’t feel like a class when the instructor lectures the whole time.

“I feel like I could have just watched this on YouTube later or something,” Knutson said.

Knutson is also struggling with the lack of her classmates’ physical presence. The majority keep their cameras off during class.

“There’s no personality. It sucks. I’ve only ever gotten personality from people during break-out rooms, and it’s like, ‘Thank god. I finally get to see you guys,’” she said.

Knutson considers herself lucky to have neighbors who are taking the same classes as she is, because she didn’t need to go out of her way to work together on assignments. They just naturally motivated each other.

Jocelyn Toscano, a student member of PEERS, a Student Health Services program dedicated to student wellness and success, recommended the ‘buddy system’ at the Motivation and Mental Health workshop. Her buddy was another student in PEERS.

“One of us would feel very unmotivated, and then the other one would be a little more motivated, and we would motivate each other,” Toscano said.

For students having a hard time finding a buddy in class or at home, Levanda said they can turn to Student Health Services.

“As a therapist, I’m a built-in accountability buddy. Let me help you. Therapy is a safe space, and it’s free with the student health fee,” she said.

Students can make an appointment by phone at (707) 527-4445 or through the student health services website, santarosa.campuswell.com.

Vasquez also said he hosts group therapy called “Convivencia” through the Humanidad Therapy and Educational Services. “Convivencias” combine food and conversation to create a relaxed atmosphere. It has an emphasis on the LatinX community, but all students are welcome. Anyone interested in joining a session can call (707) 565-2652 x 104.

As for Sapp, the time spent alone with his thoughts are his therapy.

“The fitness element is one thing, but it’s also a reprieve. Not having a cell phone, or staring at a screen, it’s like a social detox,” he said.

Sapp said he has to be mindful of the future to understand how important his classes are right now. COVID-19 won’t be around forever, and the better he performs now the more likely he is to be admitted to his preferred university, which will increase his employment opportunities. In the midst of natural disasters and social upheaval he considers his SRJC education one of the few situations he can positively influence.

Though the first half of the year may have felt like an all-time low for Sapp, he managed to turn it around by keeping a schedule, balancing work with leisure and pursuing his goals.

“Truthfully, this is the most rewarding semester I’ve had to date,” Sapp said.

Emma Molloy contributed to the reporting of this article.