After a 24-hour bus ride from Mexico City, the 12-year-old boy climbed a hill with his mother, two cousins and his aunt for three hours avoiding Border Patrol agents. Down the hill, another landscape, another language and another life awaited him.

At that time, the young boy didn’t understand his parents’ decision to move to the U.S. “I did not decide. My parents decided for me. They decided it was best for us to move here, to get better economic and educational opportunities,” said Gustavo Sanchez, now 27.

The former Santa Rosa Junior College student speaks freely about the fear he has had since 2000 when he crossed the border illegally between Ciudad Juarez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas.

According to studies from the Pew Research Center, 60 percent of the 11 million undocumented people in the U.S. live in the states of California, Texas, Florida, New York, New Jersey and Illinois. The majority (76 percent) are Latin American, including 7 million from Mexico.

The Oct. 2014 survey shows that one-third of them said they “personally know someone who has been deported or detained by the federal government for immigration reasons in the past 12 months.”

Consequently, 59 percent of Hispanic immigrants in the study said relief from the threat of deportation is more important to them than a pathway to citizenship.

Despite his illegal status, Sanchez registered at SRJC in 2005 under the AB540 law stating, “The student must have attended a high school in California for three or more years and must have graduated or attained the equivalent of a high school diploma.” The California State Legislature passed this law in 2001. It allows undocumented students to pay in-state tuition, significantly less than non-resident tuition fees.

This was the start of a paradox for Sanchez, as he was able to enroll, but unable to feel like other students. “I felt different because I knew there were many things I couldn’t get, things such as financial aid,” Sanchez said.

Above all was his anxiety of talking about his status at school. “When you meet somebody, you don’t know how he or she will react to your situation. You don’t want to take the risk somebody calls immigration to denounce you,” he said.

It is taboo among people who share his experience to talk about crossing the border illegally. “Even if I know who is undocumented, I will not talk about that. Culturally, it’s something we have to keep as secret as possible,” Sanchez said.

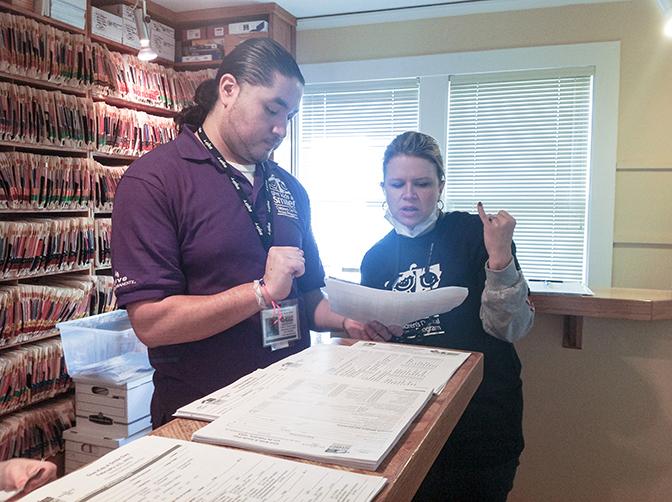

To help undocumented students, SRJC opened the Dream Center in spring 2015 to provide resources to more than 600 undocumented students. While helping them to get a degree, “The ultimate goal is to provide a workforce for the country,” said SRJC Outreach Specialist Rafael Vasquez.

Sanchez became a permanent resident in 2012, after a long administrative process. “I felt a little impatient because it took almost 12 years and I was always living in fear that they would not approve my application,” he said.

In spite of his legal status, deportation still concerns Sanchez. “Even if the law improves, there is still that fear behind everything. Even if we are not anymore undocumented, we are always afraid of something, just because we are Latinos,” Sanchez said. “Just by being Latinos, we have the stigma to be undocumented.”

Vasquez also acknowledges this contradiction. “In the criminal justice system, as long as you have a brown or a black skin, you will be considered guilty until proven innocent,” he said.

Sanchez is currently attending Sonoma State University to complete a bachelor’s degree in sociology and is finishing the prerequisites for dental school. He also works as a certified enrollment counselor for Covered California. Despite his life-long companion of fear, he built his life in the United States. American culture is part of his story. Sanchez said, “When you get used to it, you make your own happiness.”