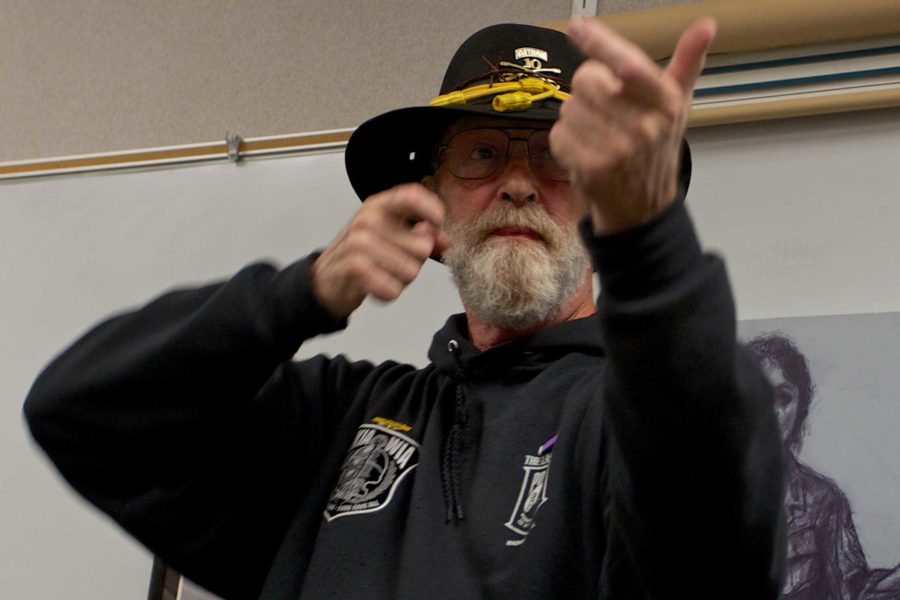

Private First Class Bruce Thompson, 10 Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, proudly received a letter around Thanksgiving 1967 from President Lyndon B. Johnson. The letter said “greetings” and informed Thompson to report for induction into the Army Dec. 7.

After completing basic training and jump school, Thompson went home for Christmas and broke his jaw. With his injury he could no longer make the jump out of an airplane, so he was re-assigned to tank school.

In the Navy Hospital in New York with a broken jaw. Thompson was surrounded by 800 broken Marines, home from Vietnam. He remembers telling his girlfriend he would never be like them. He was in the Army; it was different.

Thompson, like a lot of young men and women, was drafted into service for the ongoing Vietnam conflict, with no idea of the personal repercussions of war, or the unwelcome response he and other vets would receive upon their homecoming.

“Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another.” That is the motto worn on t-shirts, bumper stickers and in the hearts of all who had the unfortunate experience of witnessing the Vietnam War.

That motto is perpetuated in Jill Kelly-Moore’s humanities course on American culture in which she immerses students in a debate that has raged on campus for 10 years now. The debate has been going on for longer, but Kelly-Moore brings a unique experience for every student brave, lucky and caring enough to engage in it.

“I do it for them [the veterans],” Kelly-Moore said. “It is the vets’ show, and the students must participate.”

Kelly-Moore split the class in half. One side is pro-war, one is anti-war and, for the purposes of the class, the student’s actual feelings don’t matter. Like any debate or critical thinking process, students must research their assigned tasks with the goal to present the delegated side of the argument.

It’s a unique educational experience because, unlike any other part of the curriculum, real Vietnam veterans judge the debate.

In the weeks before the debate, the veterans spend a class period sharing their experiences about the war and their trip back home after their own one-year tour.

Kelly-Moore’s exercise helps both parties involved. The vets benefit by being able to speak about their plight and the students learn from the vets’ first-hand experiences the truth of war. Both benefit because the injustice is shared, like a burden, but a burden of knowledge granting those involved the wisdom to not careen down the same path and repeat history.

For the vets, every new branch of memories and experiences they share with students is a release that lightens the load they carry.

“In basic training, we used to march to the beer hall. In Airborne AIT we would jog to the beer hall, and in tank training we used to take the beer with us,” Thompson said, offering a brief moment of levity before reading from the Field Manual the definition of his new home.

A “free fire zone” is a little place in hell. The manual states a free fire zone ”is an American military term used to designate and define a geographical area in which all life is considered the enemy. Any humans or animals in this zone are fair game for all of the organic weapons of the U.S. Armed Forces, and are destroyed immediately upon detection. Plant and marine life are also considered hostile and subject to repeated defoliation by Agent Orange and other toxic chemicals.”

Early in his tour, sitting atop his APC, Thompson saw a Vietnamese man get up and run from cover. He took aim, followed the target and did what he was trained to do. “Bam! You could almost see the bullet go. Hit the guy in the back as he’s running and his arms go out and his head goes back and he plops down on the ground. He bounced once,” Thompson said.

If the man was Viet Cong, Thompson’s platoon would find his AK-47 rifle laying where he ran from. If he was a farmer just trying to sneak back into his ancestral homeland, the platoon would find nothing. The 10th Cavalry would still place an AK rifle next to the dead Vietnamese man and take a Polaroid. They were to document every kill they made. The war was about body count, Thompson explained.

To make camp in the free fire zone, the squad would all fire their weapons facing out in a circle for a minute, ceasing at the same moment to see if anyone was firing back. If not, they would send out two men in each direction with a walkie-talkie and instructions to signal on the radio every hour, on the hour.

One night, an hour came and went without so much as a chirp from one of the sentries. The squad mustered and headed off to find its comrade. What they found was a bloody foot barely attached to a boot, and a blood trail heading into the jungle. The trail was specifically left for the GIs to follow. They knew this, Thompson said, because every few feet there was a new body part and more of the blood trail.

The squad made it halfway to their comrade, “Blondie” as they called him, and they radioed in another platoon to take over the search because this was their man. The second platoon found an arm, a leg, an arm and a leg.

“The last thing they found was Blondie’s head sitting in a crook of a tree with his manhood hanging out of his mouth, his eyes open as big as a human being could open his eyes because they had castrated him and done this to him while he was alive,” Thompson said.

The first time Thompson was wounded in Vietnam was May 31, 1968. His tank hit a mine, and the four crewmembers were bleeding from every orifice that could leak blood. With concussions, the crew limped their tank with the hatches open back to a friendly Landing Zone [LZ] that the intel said was safe. Thompson and his tankmates were left alone while the working platoon went off on a pressing matter. What they didn’t know was the Viet Cong watched Thompson and his other three tankmates from the bush.

Assuming it was safe because their captain said so, the crew cracked a beer and sat on their tank. Suddenly, from the bush came a Rocket Propelled Grenade [RPG]. It flew over their heads.

The second RPG landed between Thompson’s best friend’s legs and blew up. It blew all four men into the air, and one guy they never saw again. Though peppered with shrapnel, Thompson was hit flat so the shrapnel burned his leg instead of taking it off. He looked over at his friend Mack. Mack’s right arm was gone at the elbow, his left leg gone below the knee. His jaw was gone too, and Thompson could see white things and tendons going a mile a minute, because Mack was trying to talk to him. Thompson looked up and saw another RPG being aimed at them, when all of a sudden, he heard “Whoop whoop whoop,” the unmistakable sound of a Huey chopper and the gunner working his M-60 to take out the VC next to Thompson’s tank, while kicking out C-rations (the predecessors of MREs, “meals-ready-to-eat”).

Everyone who made it onto the chopper lived, including Mack. Thompson didn’t get on the chopper. He stayed on the ground and moved with a squad to the closest firebase, where he was designated to be sent back to the States to recover from his injuries.

Thompson said he gave away his M-16, ammo and rations, but held onto his .45 pistol, in preparation to leave. Suddenly the Viet Cong overran the base. A woman VC armed with an AK-47 charged and fired at Thompson in his machine gun nest. She had it set to automatic fire, instead of single shot. The shots rode up and only hit Thompson once in the leg, a through-and-through, and he unloaded four rounds into her, killing her. He tried to crawl over her to get out of the bunker but, through her blood and his, there was nowhere to go. He lay still next to her in a pool of blood, facedown with his pistol held cocked under his own chin, just in case he was discovered.

The VC overran the base and went to search for survivors. Thompson recalls hearing the VC find a GI. “I never imagined a human able to make those sounds, but I never imagined listening to someone be skinned alive,” he said.

A 2012 report from the office of Veterans Affairs estimates that an average of 22 vets commit suicide a day. More than 8,000 veteran suicides a year are confirmed and it is nearly impossible to track all of the deaths. Overdoses, accidents, single occupant vehicle collisions are all examples of deaths that are difficult to determine intent.

In 1967, Specialist Anthony Tate, originally from Chicago, found himself in court at age 17. The judge offered him a choice, jail or the army. For Tate, it was an easy choice to make.

“Do you want me to sugarcoat this, or drop is like it’s hot?” Tate began his presentation to Kelly-Moore’s class. A warning, given with a smile, readily accepted by the class to “drop it like it’s hot.”

Tate continued, divulging a brief jump ahead in time with his grocery list of degrees. One AA in early childhood development, two bachelors’ in sociology and psychology and a master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling. He knows how to make a point.

“Did I hide? Yeah, 40 years. I didn’t tell a soul I was a Vietnam Vet,” Tate admitted.

A product of the projects, Tate was no stranger to survival. He fought his way to school past three gangs in three different projects, to fight during recess against alley kids. Seeing someone fall from a 14-story project or shot on the street was not alien to him.

Yet Chicago did not prepare him to fight 5-year-olds strapped with explosives on their chests or shooting from between their mother’s legs in the rice paddy. Every Vietnamese person was a potential enemy, from 5-year-olds to mothers, fathers, and all the way to the oldest person in the family tree.

First Lt. Kate O’Hare-Palmer, an army nurse who trained in L.A. county hospitals during the Watts riots in 1965, had seen gunshot wounds and plenty of traumas before arriving in Vietnam.

O’Hare-Palmer told the class between 7,000 to 10,000 women served in Vietnam.

Freshly 22, she arrived in Vietnam and, after being awake for 24 hours, a helicopter took her to her post. Along the way, the chopper was called to an emergency and needed to drop her off before they headed to their new task. The chopper left her at the top of a desolate mountain LZ. O’Hare-Palmer hadn’t even been issued her .45 pistol yet. She hid in the trees with her duffel bag until sometime later another helicopter crew came to finish her transfer.

Having landed at her destination base in Chu Lai, O’Hare-Palmer hit the rack for some shut-eye. Two hours later she was awoken and ushered into an Operating Room [OR], not even able to be completely gowned and gloved. Soldiers yelled at her to just get ready. The patient was in a pressurized bag and had a nicked aorta. When the bag was opened O’Hare-Palmer had to act quickly before he bled out.

O’Hare-Palmer recalled gory conditions in the medical unit. “We were covered in blood. We would slip in blood,” she said.

One night, three weeks into her tour as the junior nurse on staff, O’Hare-Palmer was assigned the night shift. Her training in the ER back home helped her respond to incoming traumas. That evening eight GI’s came in with their legs macheted off below the knee. Fifteen minutes later soldiers brought in two of the VC that did it, whom American soldiers had kept alive with hopes of interrogating them later. All were placed in the same ward.

“This is very moral issue here all of us will face, all of you will face,” O’Hare-Palmer explained. “How will you handle working with someone you do not want to be with, or you think they have done something really wrong? How are you going to handle that? We faced that every day.”

It wasn’t until later in the war the military set up different bedding units in the field hospitals for the enemy to receive medical assistance.

When she came home at 23-and-a-half, O’Hare-Palmer said she felt 105. “I only felt comfortable with other vets,” she said. But she wouldn’t talk about it at the time, not even with her own brother, who spent tours in Vietnam as well. She didn’t want anyone to know she was a vet for a very long time.

When they came home, Vietnam veterans were spit on, yelled at and called “baby killers.” There were no PTSD-specializing doctors, because PTSD hadn’t been discovered as a real disorder. Vets were publicly punished for reporting for duty. They were treated as though they had enlisted to an all volunteer military to go and kill people in another country. This was not the case, as many were drafted to report for duty, regardless of their own views on the war.

Kelley-Moore’s ensuing class debate took place two weeks after the students caught what was dropped, hot, in their laps. In the first session, one judge voted for the anti-war argument, the next day, he voted pro-war. For the vets, it wasn’t about whom they wanted to win; that much was obvious.

“We know the story,” Thompson said.

Kelley-Moore designed the event to expand the students’ minds, and Specialist Tate let them know when he felt they did not perform up to muster in the open debate discussion portion.

After the debate, student Billy Ambrose said, “It’s hard to be pro-war, but I understand why it’s needed and there are two sides to every story. There is no downside to understanding both sides of everything.”

Student Aja Harris didn’t know much about Vietnam, other than she has close relatives like uncles and her grandpa who fought there, but still don’t discuss it. “They aren’t open about it like these gentleman are, so this really helped me understand what they went through and just what everyone went through on both sides,” Harris said. “Having a 2-year-old daughter and a 3-year-old son, I feel like I have this information, this knowledge that I can pass off onto them.”

Student Frank Moran argued for the pro-war side, despite his anti-war sentiment. “It was a hard decision this country had to make. You can’t really make a conclusion on it,” Moran said. “It’s just one of those things you have to accept; that there are many different points on it and you can’t just stamp it and say ‘there it is.’ It’s not so much about what we believe, it’s about you have to think about it from every standpoint.”

Thompson said what’s going on in the world to day is similar to what his generation experienced in the ‘60s. “Some stuff doesn’t change. What we hope is that your generation will do maybe a better job than we did,” he said. “Because we kind of, I feel we kind of let humanity down a little bit, and maybe we could have done a better job. So we are going to leave it up to you to do a better job.”