Sonoma State University featured the Reel Rock 9 Film Tour showing of Sender Films’ “Valley Uprising” on Nov. 6. The documentary will not be screened at any big-screen theaters but the Blu-Ray, DVD and download is available on www.senderfilms.com for $29.95 and under.

“Valley Uprising” follows the evolution of rock climbing in Yosemite National Park from daredevil mountaineering to a socially accepted, yet not always lawfully accepted, athletic sport and lifestyle.

SSU’s Associated Student Productions, Campus Rec Adventure Programs and Campus Life put on the free, well-attended screening and raffled off climbing gear donated by local businesses.

“We just love seeing people from Santa Rosa, Petaluma, from even down near San Francisco,” said Kevin Hill of Campus Rec Adventure programs, an avid rock climber who has helped SSU host the Reel Rock Film Tour for the last five years. “Everybody coming together and just really enjoying the movie as a community.”

The story of these rebel climbers comes to life through what Sender Films calls “digitally-animated archival photography.” Layered black and white photographs of Yosemite’s majestic cliffs create an effect similar to a Japanese woodblock print, with shadowy mountains fading into the distance. Digitally enhanced stills of the landscape and the “Golden Era” rock climbers are contrasted by the rugged ’60s film footage of the bearded men in hiking boots pounding metal stakes into the side of a cliff with a mallet.

Like many social movements in post-World War II America, the rock climbing revolution embodied a counterculture lifestyle and spurred numerous flare-ups with law enforcement.

Following the trend in law enforcement during the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam protests, Yosemite Park Rangers outlawed rock climbing and militarized their forces to combat the longhaired freethinkers.

The film states that before the emergence of rock climbing, park rangers were biology majors, and now they are trained like police.

There is a seven-day camping limit in Yosemite Valley during the summer climbing season and a 30-day camping limit in all of Yosemite Park for the calendar year.

These rules were implemented, according the climbers interviewed in the film, to limit their ability to set up big climbing projects, spend time on difficult routes and recreate the climbing culture of Yosemite’s “Golden Era.”

The rangers feel they need to protect the landscape for the millions of tourists who visit the park each year and don’t want to see chalk marks all the way up the face of El Capitan.

Though tensions are still high, the end of the film sheds light on the fact that both climbers and rangers have the same mission in protecting the natural beauty of the park.

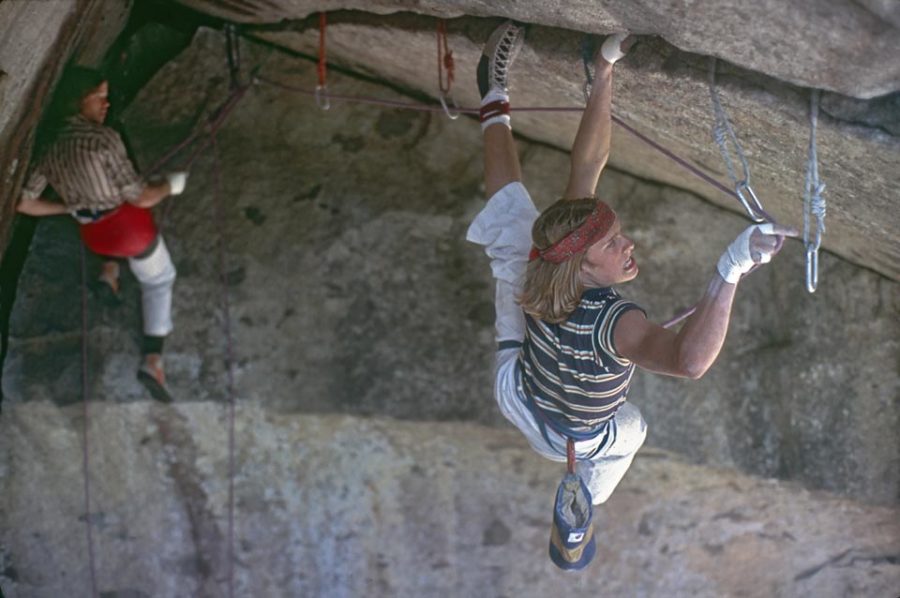

As the “Golden Era” progressed into the “Stone Masters” era of the ’70s, climbers began to “free climb,” using only their body power, instead of aides like rope ladders, to ascend the cliffs. This style of climbing advanced the sport athletically and created the image most people think of when they picture rock climbing.

Interviews with the “Stone Masters,” or, in their own words, “stoned masters,” are bolstered by vintage footage of these top athletes training in the wilderness and dropping acid on the side of cliffs.

In search of a bigger rush, climbers and adventurers of the modern era, the “Stone Monkeys,” face new challenges with law enforcement. First-hand footage and interviews with the adrenaline junkies who ignore laws against opening a parachute give the viewers a never before seen glimpse into their incredible, criminal lives.

The three eras create the storyline of rock climbing and give historical context for each generation. This film appeals to any lover of nature, adventure, the ’60s and, of course, climbing.