“Goodness, that’s awkward,” Crabbin said.

“‘Goodness, that’s awkward’? Is that what you say to people after death?” Holly Martins asked.

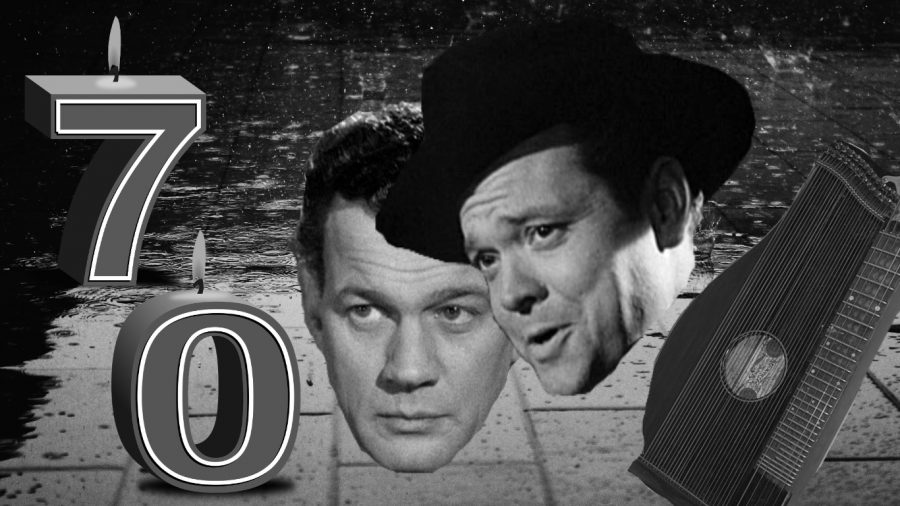

On this day 70 years ago, the shadowy world of film noir was expanded and epitomized by the release of “The Third Man.” The film is founded upon an evocative zither score by Anton Karas, stark cinematography depicting post-World War II Vienna and a monumental—if brief—performance by another legend of film noir, Orson Welles. But does “The Third Man” hold up in a world where its aspect ratio, color and genre are now obsolete?

Since “The Third Man” was released, we’ve seen seven magnificent decades of film history, including the entire life of contemporary master Paul Thomas Anderson, 35 Godzilla films, 42 years of Star Wars and 98 Marvel films.

The film opens on a shot of a zither, a stringed instrument composer Anton Karas used to score the film. Instead of a hard-boiled string section or a dark jazzy score, director Carol Reed elected to use Karas’ zither music after stumbling upon him at a production party.

While “The Third Man Theme” that opens the film might sound light and jaunty—more akin to an episode of SpongeBob than a detective film—the zither proves itself as versatile as an orchestra in “The Third Man.” The score sounds sinister and dramatic in some scenes and joyous in others. The light quality of the instrument is used ironically in one scene as the main character, Holly Martins, portrayed by Joseph Cotten, runs from a mob. A later chase scene stars the film’s mysterious central figure, Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles. The score is anxious and disorienting, bringing us into Martins’ shoes as he runs down the rain-slicked streets of Vienna.

After the film’s opening zither shot, Carol Reed narrates a documentary-style introduction explaining how Vienna, while retaining most of its beautiful architecture and statues, is now debris-filled and occupied by four separate WWII powers: the French, British, Americans and Soviets. His narration is casual; “Wait, I was gonna tell you,” he says, interrupting himself. Reed’s narration, informative but sarcastic like Jordan Belfort in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” informs us the film will be serious, but it knows how to have a little fun, too.

The plot begins when washed-up American pulp novelist Holly Martins arrives in the cultural melting pot of Vienna. When his childhood friend Harry Lime offers him a job, Holly arrives to find Lime dead, killed while crossing the street just hours earlier. The rest of the film follows Martins’ attempts to uncover what really happened to Harry Lime.

One by one, Martins meets Lime’s shady friends and acquaintances, including the eccentric Baron Kurtz, Lime’s best friend and implied right-hand man; Dr. Winkel, a “medical adviser” who, along with Kurtz, was seen at Lime’s death with the eponymous “third man;” and Czechoslovakian immigrant Anna Schmidt, Lime’s lover.

While stellar acting and cleverly used music are strong indicators of a movie’s quality, there are two even more important components that most contribute to the modern watchability of “The Third Man.”

The first is its pace, which is where many films from the early era of cinema fail to engage modern audiences. In “The Third Man,” there’s hardly a moment to catch our breath, as we travel with Martins from location to location, meeting more pieces in a puzzle that seems to grow by the minute. It seems as if the whole town knows something Holly Martins doesn’t.

The second modern component is the cinematography. Throughout the film, the viewer is exposed to stunning street-wide views of Vienna, lavish interior design and images that perfectly juxtapose the city’s beauty with the rubble and ruins that scarred it during WWII.

Like other film noir cinematographers, Robert Krasker uses dutch angles, in which the camera is tilted on its side, to conjure feelings of unease and discomfort. “The Third Man” takes advantage of another film noir staple: shadows. The film successfully uses shadow in both background and foreground scenes.

Most scenes feature intricate patterns of shadows acting as curtains behind the action, but the film’s greatest use of shadow is in introducing the very-much-alive Harry Lime to the audience.

A cat nuzzles up against black cowboy boots. A drunk Holly Martins calls out to the darkness. A light shines from a neighboring home, illuminating the man for all to see: Harry Lime. He cracks a grin before the light goes dark. When the light comes on again, he has disappeared.

In the film’s most famous sequence, Martins and Lime converse on a ferris wheel. The characters act out a duel of words, full of doublespeak and unshared knowledge.

Despite the fact that Welles only did a week of work for the entire film, leaving him with five minutes of total screen time (most of it in this scene), his performance is chameleonic. While his roles in earlier film noir like “The Lady of Shanghai” and “The Stranger” were campy and overacted, Welles gives his all in “The Third Man” and beckons the audience to study every line of dialogue, every facial expression.

“The Third Man” currently holds a 93/100 on Metacritic from 30 critics and a 99% on Rotten Tomatoes from 78 critics. By classic film standards, it is nearly a perfect film, but when more modern metrics are brought in the film begins to show its age.

The film does not pass the Bechdel test, in which two named women in a film must have a conversation about something other than a man. The film also doesn’t feature a single person without white skin, which isn’t uncharacteristic of old films, but could be considered uncharacteristic of a European town under occupancy by American, British, French and Soviet forces.

One scene, however, could be read as a coded act of feminism. In the final scene, presumed love-interest Anna walks down a seemingly infinite stretch of road towards Martins, who has elected to stay behind for Anna at the risk of missing his flight home. Anna, who director Reed ensured wore plain clothes throughout the film in lieu of something more exploitational, walks toward the camera and continues past it instead of joining Martins. He sighs, lights a cigarette and the film fades to black.

“The Third Man” isn’t as important as Welles’ earlier directorial work like “Citizen Kane,” but it is a unique vision, and its influence can be seen in the films of Martin Scorsese, who is a staunch admirer of the film; the music of Jack White, who named his record company Third Man Records after the movie; and the films of the Coen brothers, whose cinematography is heavily reliant on a stream of memorable secondary characters.

The influence of film noir can be found in modern films like “No Country For Old Men,” “Drive” and “Nightcrawler,” which all feature morally ambiguous characters searching for truth and power in a dark, fatalistic world where the good guys are bad and the bad guys are worse. However, the genre has seen so few entries in recent years that film noir is practically extinct.

We may never see another true film noir. One thing’s for certain: unless Carol Reed, Anton Karas and Orson Welles come back from the dead, there will never be another film quite like “The Third Man.” Its cocktail of film noir style, elegant audiovisuals and lifelike character portraiture means not only does the film hold up, but it will continue to be studied for years to come.

April • May 21, 2022 at 6:49 pm

This review is written by a person who has been exposed to the worst of the cultural dictates of the late 20th and early 21 century. Way too worried about the rules of feminism and how many white faces dominate the scenes.

Clayton Miller • Sep 15, 2023 at 7:14 pm

Agreed.