Biographies are easy reads. It’s inherently interesting to read about a life that produced intellect, heroism or art. But a good biography is insightful, with the power to contextualize history and reframe the present.

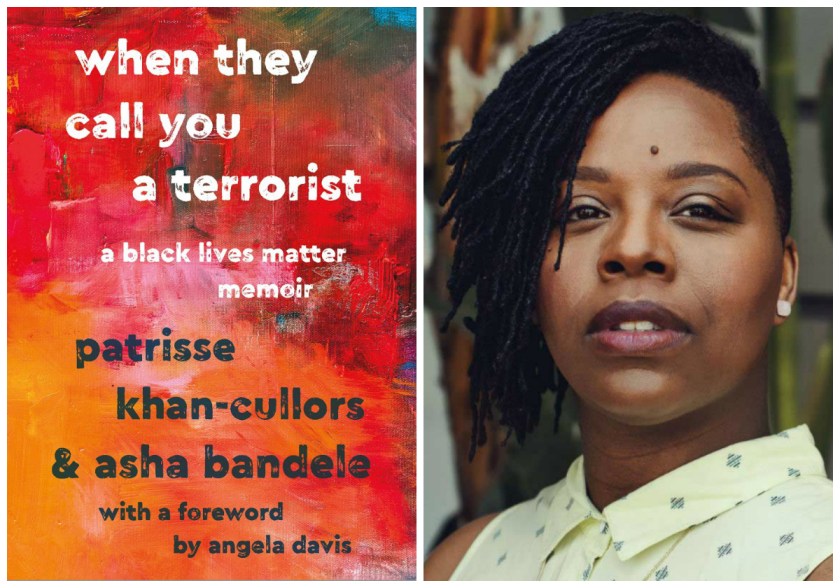

Patrisse Khan-Cullors’ new memoir, “When They Call You a Terrorist,” takes this historical approach and lacks no heart because of it. The book is co-authored by Asha Bandele, with whom she partnered on written pieces in the past. Khan-Cullors is most famous for starting the #blacklivesmatter movement, along with Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi. She grew up in South Central Los Angeles at the height of the Reagan-declared war on drugs in the 1980s. Khan-Cullors got involved with the Strategy Center at age 17, where she honed the art and activist skills she uses today.

The book details a life of love, devastation and activism that inspired a movement. For those who don’t understand the hashtag or are interested in recent history, “When They Call You a Terrorist” is accessible and endearing food for thought.

It’s not always easy to ingrain history the way it is taught in school. Biographies have the power to pull readers into history, connecting them to the people within the events.

We can read reports like “The Sentencing Project,” which lists the U.S. as the world leader in incarceration, with 2.2 million currently behind bars. We can read that although crime has not shifted dramatically, the number incarcerated increased by 500 percent in the last 40 years. We can read about the number of people with mental disorders in prisons compared to health centers.

Khan-Cullors pulls us into her journey as her friends, family and community members face the harshest application of the law. She shows her brother Monte’s journey in jail as he is routinely beaten, denied water and put in solitary confinement after a schizoaffective disorder diagnosis. She details continually losing Monte to the prison system from which he returns more broken each time, a second-class citizen in the eyes of the law.

There are studies that examine the lack of resources in communities of color, but it is hard to understand the human effect. Khan-Cullors makes it easy by walking us through her childhood without parks, grocery stores beyond 7-Eleven or parents who can afford to stay home from their third jobs.

She takes us to the makeshift alleyway playgrounds that kids created and were routinely frisk-searched in. Kids in her neighborhood were locked up for talking back, tagging, smoking weed, underage drinking or literally wearing the same T-shirt. Khan-Cullors shows the targeted policing behind the war on drugs and gangs for what it is: a continuous war on black communities.

People throw around big terms like the prison industrial complex, but Khan-Cullors illustrates the way prisons are filled and whom they directly benefit. She explains the laws that give police impunity to search each black body they set their sights on. She describes the small towns where prisons are the big industry, and the big corporations that profit from the nearly-free labor.

Khan-Cullors talks about learning to love—in many capacities—while a target is trained on your back. She reflects on what it means to love deeply for people seen as expendable in the systems at play.

Khan-Cullors writes, “When hate and the harshest version of living dominate, when even the worst assaults are blamed on the victims, when bullying has become ever present, limitless, we have come to say that we can be more than the worst of the hate. This is what we mean when we say Black Lives Matter.”

The word terrorism is used in a way that distorts all meaning; Khan-Cullors explains how a life can be intentionally streaked with terror, and how those in power can flip the term, and at any time call you a terrorist.